Four years ago, George Floyd was choked to death by a police officer after trying to use a possibly counterfeit $20 bill at a Minneapolis convenience store. Widespread outrage about the killing spurred the largest U.S. banks to vow to do their part to fix the inequalities in the American financial system.

JPMorgan Chase announced it would spend $30 billion to address social and economic inequities. Bank of America and Citi each pledged $1 billion. Wells Fargo promised $450 million, U.S. Bank $116 million.

Today, the banks say they've put this money to good use.

JPMorgan Chase says it's invested $30.7 billion in racial equity initiatives, mostly in the preservation and construction of affordable housing. Citi says it has provided growth capital and technical assistance to minority depository institutions, invested in Black-owned businesses and affordable housing and is working to

Wells Fargo has committed $150 million to a special purpose credit program. Bank of America says it's committed $1.2 billion to advance economic opportunity, focusing on jobs, affordable housing, small businesses and health equity. U.S. Bank says it has stepped up lending to minority owned small businesses and mortgage down payment assistance in underserved communities.

Despite the tens of billions of dollars banks have spent, the racial wealth gap has actually widened over this time period.

According to the Federal Reserve Board's

And while 72.7% of white Americans own their own home, only 44% of Black Americans do, according to the

"The reality is, white America and people of color America are living in two different financial realities," said Silvio Tavares, CEO of VantageScore. "And as Americans, we know that that's not sustainable. Putting aside the moral aspects of it, just as a business proposition, that's just not sustainable."

Impact of the racial wealth gap

Aaron Long grew up in the 1980s in St. Louis.

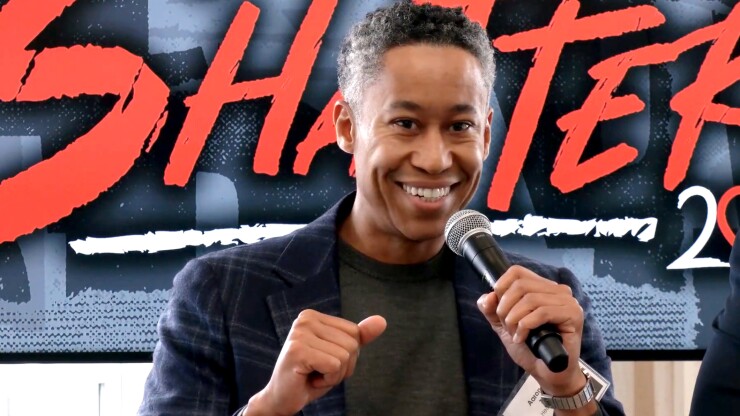

"In the inner cities, you had the drugs, the crack, all of that stuff," said Long, who is head of client advisory and strategy at Zest AI, a technology company with an AI-based lending platform. "Wealth affects two important things on the household level. It affects education and the environment that you're in. Without being able to improve those, you have this continuous cycle."

People will sometimes blithely say that kids born in disadvantaged neighborhoods just have to pull themselves up by their bootstraps, work hard and overcome their circumstances. But Long says this cliche is not a realistic prescription to improve the lives of children growing up in poverty.

"It's super tough to get out," he said. "You don't have the skills to do it. You don't have the education to do it. You don't know where to go to do it."

Kids who grow up in poor inner cities have "small dreams," Long said, "because that's the only thing that you know how to dream about — you don't see anyone in your family that you can pick up the phone and say, 'How do I start a business?'"

And it's been this way in the United States for decades. In the mid-1960s, the average Black household was making around 57 cents per dollar compared with the average white household, according to Long. Today it's around 62 cents.

"You can see over the generations that the wealth gap is still there," Long said. "If we continue with that trajectory, it'll be well over 500 years before we're able to have no wealth gap at all."

Racism and systemic issues still prevent African Americans from getting approved for credit, said Tonita Webb, CEO of Verity Credit Union in Seattle.

"It is so traumatizing for some to even just walk into a bank to apply, because of their past experience," she said. "I know people who won't do it because they think the financial services industry is not for them because of all the nos that they have received."

Some of those nos may have been for sound creditworthiness reasons, she said, but banks frequently also don't take any steps to help move these applicants forward. Others are rejected "just because that's been the history of our financial services industry," Webb said.

A long history

Wole Coaxum left his job at JPMorgan Chase and started a fintech called Mocafi after Michael Brown, an 18-year-old Black man, was shot and killed by a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014. A grand jury subsequently declined to indict the officer, and a firestorm of protests followed. Mocafi works with governments and nonprofits to provide financial services to underserved consumers.

"Watching the folks in Ferguson in the streets protesting, for me, was an instance of people fighting for social justice, but also a need for economic justice and a lack of access to opportunity," said Coaxum. Their lack of resources was part of the reason they were in the streets, he thought.

In Coaxum's view, the racial wealth gap "is deeply rooted in the bones of this country, and I'm reminded of it regularly."

For instance, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt's G.I. Bill was designed to help World War II veterans obtain affordable mortgages guaranteed by the Veterans Administration. But the loans were made by white-run financial institutions that rarely provided mortgages to Black people.

As a result, the vast majority of the benefits went to white service members. In one example, "fewer than 100 of the 67,000 mortgages insured by the GI Bill supported home purchases by non-whites" in the New York and northern New Jersey suburbs, historian Ira Katznelson wrote in the book "When Affirmative Action Was White: An Untold History of Racial Inequality in Twentieth-Century America."

"The biggest economic driver of the 20th century that enabled us to become a superpower post World War II excluded Black people," Coaxum said. "From a historical lens to a modern lens, there is a consistent thread of Black folks having less access to wealth building opportunities," Coaxum said.

What it would take to shrink the racial wealth gap

The racial wealth gap is a huge, multifaceted problem with experts disagreeing over how to best close it. Some consider increased home ownership the answer, because of all the socioeconomic benefits that stem from that. Others focus on improvements in wages, basic income, increased savings or short-term loans that people can turn to in a pinch and, say, get new tires for their car so they can keep going to work. Others still think artificial intelligence will help. Many believe it will take a concerted effort by the banking industry, fintechs and government.

"It is a question I grapple with all the time," Webb said. "And here's where I land. We can make a difference for our small community and our small membership. But I think to make a difference for the overall wealth gap, the financial services industry has to make a decision to provide programs to undo systemic practices and policies and use technology, such as AI, that looks at other things besides the credit score, which we know is systemically created to have an advantage for some and a disadvantage for others."

Financial services firms could provide education to help people understand the financial system and how to navigate it, she said. And products need to be developed for the purpose of shrinking the wealth gap.

If more than 70% of white people own homes and only 40-plus percent of Black people do, "there has to be something specifically done to close that gap," Webb said.

It's not enough for the government to put out a policy that companies can no longer discriminate, Webb said. There are already laws, including the Fair Housing Act of 1968 and the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, that prohibit lending discrimination based on race — and yet these issues persist.

"We've had decades and years of discrimination," she said. "We also have to create programs that give access where folks didn't have access before in order to shrink that gap. We've got to remember there are underserved communities that are way behind, so they're playing the catch-up game."

Coaxum sees the racial wealth gap as a market failure that would be best solved in partnership with the government. Banks are driven to target more affluent — and in general, white — customers. These consumers tend to have more assets that the banks hope to help them invest. Originating one larger mortgage for a more expensive home is seen as less of a hassle than making several smaller loans for more modest houses. Credit decisions tend to be easier, and lenders feel more assured they will be paid back.

"If left to the private sector, it's going to come along in a drive towards efficiency that doesn't necessarily have a wide net that is systematic, sustainable and strong enough to close the wealth gap in our communities," Coaxum said.

Until local, state or federal government does something, "we're just going to have a series of really smart people building really interesting companies, but may not have the scale that's required to really meaningfully shift the needle," Coaxum said.

One thing governments could do is rethink how they get resources to the unbanked and underbanked of their communities and work with partners to do this digitally, rather than through checks and benefits cards, Coaxum said.

Coaxum's fintech, Mocafi, for instance, works with New York City to provide immigrants with debit cards they can use to receive help.

New migrants to New York are processed at the Roosevelt Hotel in Manhattan. They used to receive food deliveries every three days but this inevitably meant that uneaten food was thrown out, making the effort expensive and wasteful. With Mocafi, the city is testing giving immigrants a preloaded debit card so that they can buy their own food. According to Coaxum, this new system is a third of the cost of having food delivered and gives participants more choice in what they eat. It also puts dollars into the community and reduces waste, he said.

The credit gap

Tavares' family came to the United States from Angola when he was 10 years old. His mother was a physician and his father was a politician turned professor. His parents found a house they liked in a safe neighborhood with good public schools. His father went to the local savings bank to apply for a mortgage.

"He fully anticipated that he would be approved because he had a Ph.D.," Tavares, VantageScore's CEO, recalled. "He was a professor at a prestigious university, and he had money in the bank."

The application came back a couple weeks later: Denied. When his father walked into the bank branch to ask why, he was told it was because he was an immigrant and didn't have a credit report. Tavares' parents talked about this a lot at the kitchen table.

"I was just starting to learn English, but I kept on hearing this weird word, 'mortgage,'" Tavares said.

It's degrading and discouraging to be declined for credit the way his family was, Tavares said.

"When you say to somebody, you are not creditworthy, what they often focus on is not the credit part, but the banker saying, 'You are not worthy,'" he said.

That stigma is part of the reason why African Americans and Hispanics often are suspicious of the banking system, "because they have a relative or somebody that they know who was very hardworking, very focused on savings, but then when they applied, they got denied," Tavares said.

In Tavares' case, his father decided to use the family's entire savings to buy the house, against his mother's objections that if any one of them got sick, the family would be ruined. His father said the family would build a credit report over three or four years, refinance and get the money back.

"They were able to do that, and that's what paid for my engineering degree, my MBA and my law degree," Tavares said.

Starting in the fourth quarter, the Federal Housing Finance Agency will require lenders to use VantageScore 4.0 scoring models in order to sell mortgages to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. VantageScore 4.0 uses machine learning and trended credit data to assess the creditworthiness of people who have limited credit history. Trended data shows a person's pattern of financial behavior over a set period of time, generally about 24 months. Tavares estimates that this will enable 4.9 million new borrowers to become eligible for a mortgage and 2.7 million will be able to easily get a new mortgage because their credit score will be above 620.

Everyone who is creditworthy should have access to a mortgage, which is the key to unlocking financial stability, Tavares said.

"If you own a home, all sorts of great things flow from that: better access to public schools, a financial security cushion when times get rough, because you can dip into your home equity," Tavares said. "Eventually when kids finish public high school, they can go on to college and you can tap your home equity to finance that."

Besides mortgages, access to other types of credit, such as an auto loan, can make a significant difference in closing the racial wealth gap, experts said.

"Being able to access a car directly translates into better opportunities to tap new work opportunities," Tavares said. "It gives you the ability to find the best job in your area, the one that pays the highest wages, and that translates directly into increased wealth and closing that racial wealth gap."

Solo Funds, a Los Angeles fintech that hosts a platform on which people in disadvantaged communities make small loans to one another, is closing the racial wealth gap for its members, according to co-founder Rodney Williams.

Solo Funds' borrowers have saved nearly $30 million in fees they would have paid had they used a credit card, Williams said. And people who lend on the platform are seeing their money grow for the first time in their lives, he said.

Solo doesn't have the budget to do much marketing, he said.

"But if you go into the inner city community, if you go to the barber shop and you have a flat tire, someone's going to say, use Solo," Williams said. "That's just the word on the street."

The need for alternative data

Some blame the banking industry's reliance on the FICO score and traditional credit history data for the persistence of the racial wealth gap.

"There's not enough data in the traditional credit bureau system to give lenders confidence about how to lend to segments that are not well represented in the credit bureau file," said Misha Esipov, founder and CEO of Nova Credit. "To better serve those segments, you need to have a platform which includes the infrastructure, the analytics and the compliance to better understand those segments."

Nova Credit's platform provides credit bureau data (including from other countries), bank account transaction data and rent payment history as well as analytics and income verification.

"Our belief is that when you have more data and more visibility, you can responsibly serve these segments that the traditional credit bureau model just doesn't quite capture," Esipov said.

One in five Americans have no credit score because they don't have enough credit history to be scored, said Brian Hughes, former chief risk officer at Discover.

Yet 95% of American adults have a checking account, "which is a great source of data and payroll data," Hughes said. "There's light that can be brought to these customers that don't have a credit score. And once it's brought, then adoption can happen and if adoption happens, greater inclusion happens," he said.

Webb at Verity Credit Union agrees the FICO score is not sufficient to determine creditworthiness. FICO scores are calculated using data in credit reports that is grouped into five categories: payment history, amounts owed, length of credit history, new credit and credit mix. (FICO also offers UltraFICO, a model through which consumers opt to have a bank incorporate an analysis of their bank account data into their score. VantageScore offers a similar product, VantageScore 4plus.)

"A FICO score really only looks at five or six different pieces of data," Webb said. "There's lots of other ways that we can get more information about somebody's character. Someone shouldn't have to pay for the rest of their lives for maybe a blip in their lives."

For instance, a consumer could get a cancer diagnosis that impacts their ability to work for a time, she said.

"That is life and that is part of credit," Webb said. "You can't make somebody pay for this for 10 years. The situation can improve and no longer be a mitigating factor to how they're going to pay their bills moving forward."

Banks' and credit unions' efforts to use alternative data, such as checking account data, to inform lending decisions is a step in the right direction, in Coaxum's view.

"But you can't forget that check cashers and pawn shops and payday lenders are serving this customer, and those data elements are not in the algorithms," he pointed out.

If algorithms had data from these sources, banks would have "a pretty good shot at maybe reimagining lending for this population," Coaxum said. "That dataset would allow you to come up with some more interesting and creative lending solutions that you could feed the algorithms that might open the market up."

While check cashers and pawn shops don't report repayments of loans to credit bureaus, they do sometimes report when people don't repay, creating a double negative for people who don't have access to bank branches. The same is typically true for rent payments — the landlords that do report to credit bureaus tend to only report missed payments, not payments.

Some see hope in a movement to get landlords to report tenants' rent payment to the credit bureaus. This could give people who can't afford to purchase a home a way to build a credit history and work toward possibly obtaining a mortgage.

Esusu, for example, facilitates the reporting of on-time rent payments to credit agencies. It partners with government-sponsored housing enterprises like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

The company says it has unlocked billions of dollars in credit and facilitated access to loans, mortgages and student loans for individuals who were previously underserved.

"The tangible increase in credit scores among renters and the creation of new credit tradelines demonstrate progress in bridging the racial wealth gap by providing financial opportunities to those who were previously credit invisible," said Samir Goel, co-founder and co-CEO of Esusu.

AI-based lending

Some bank and fintech leaders think AI could help close the racial wealth gap.

"We are in the early stages of assessing the transformative power of AI," said Carolina Jannicelli, head of community impact at JPMorgan Chase. "We do believe that advancements in technology, as has been the case throughout history, have the potential to advance our economy and positively impact communities."

Since Verity Credit Union began using Zest AI in lending decisions last year, it has seen a significant increase in the number of approvals for protected status applicants, including a 271% rise for individuals aged 62 and older, a 177% increase for African Americans and a 375% uptick for Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. Approvals for women increased by 194% and by 158% for Hispanic borrowers.

The $809 million-asset credit union tries not to decline people without helping them get to a yes, Webb said.

"Not everyone has been told how to navigate finances," Webb said. "We also understand, especially for traditionally underserved individuals, there's a lot of trauma around finances. So dealing with those issues that may be present for folks helps get them in the position of a yes for some of the loans."

The credit union is using Zest AI software to make unsecured auto loans, credit cards and personal loans. It meets quarterly with Zest's data analytics team to review data on the results.

Tia Narron, chief lending officer at Verity Credit Union, considers a borrower's current ability to repay the loan a much stronger indicator than if the person's credit history indicates a brief past financial challenge.

The company hopes to use this technology beyond lending, for things like preapprovals and account opening.

AI's unintended consequences

As the many recent examples of inaccuracies, hallucinations and bias in generative AI models show, AI is obviously not a cure-all.

"I believe that technology is an accelerant, not necessarily a problem solver," Coaxum said. "It could make the problem worse if we're not careful."

The use of AI to make decisions doesn't equate to treating people equally, Coaxum said, because AI models are dependent on the datasets they are fed. And where banks aren't serving minority communities, or aren't serving them much, they lack the necessary data.

According to the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the total number of U.S. bank branches has declined by 5.6%. The number of so-called banking deserts — neighborhoods where no banks have a physical presence — has increased by 217, and the population living in banking deserts has increased by more than 760,000 people.

A consequence of under-serving minority communities is that when banks are building datasets to inform the algorithms they use for lending decisions, they don't have a large enough data sample to be able to really understand payment behaviors of these customer bases.

"It becomes, in my mind, challenging to have a robust lending framework," Coaxum said. "Not because they're not good people, not because they don't want to, they just don't have the customer base."

There is a chance AI could perpetuate discrimination, resulting in further unequal treatment of racial minorities, Goel said.

"To mitigate the risk of worsening the racial wealth gap, we have to ensure that AI systems are ethically developed, regularly audited for biases, and are regulated to prioritize fairness and inclusivity in financial services," he said.

AI systems used in commercial settings are typically trained on past human-generated data, pointed out Daniel Susskind, economics professor at King's College London, senior research associate at the Institute for Ethics in AI at Oxford University and author of the book "

"So a system that determines who gets a job interview is in part trained on the sorts of decisions that human interviewers have made in the past," Susskind said. "The great risk, and we see this in practice, is that the sorts of biases that people exhibit in human decision making simply get replicated and in some cases magnified by these systems, which are learning how to act from human experience."

When AI models do demonstrate biases after being trained on human data, "quite often they tell us interesting and uncomfortable things about ourselves," Susskind said. "They hold a mirror up sometimes to our own biases, some of which we didn't know that we had."

In a paper entitled, "

"Models are trained on historically biased data," said Salinas de Leon. "So when you put bias in, you will get bias out on the other side. If we continue on this path without properly reviewing the models and the training data they are given, then we'll definitely increase the gap because we're unaware of all the biases that they were trained on."

On the other hand, algorithms have less intentional bias than humans, Nyarko pointed out.

"Algorithms don't have animus," he said. "In the law, we care a lot about, do you have discriminatory intent? When algorithms make decisions, they don't have the intent to hurt minorities. They might do that as a byproduct, but for humans, there can be specific intent or subconscious biases."

According to Laura Kornhauser, founder and CEO of Stratyfy, transparency is key for a fintech providing AI-based underwriting and fairness models. Many models are tested after they've made decisions, which can make it hard to revise the models, she said.

"That ends up being really essential in this bias question," Kornhauser said. "If I'm just feeding the data we have into a machine, even if I'm doing some smart things around dual optimization and adversarial biasing, if I can't see inside the guts of the machine and make changes to how it's working, then the risk of that bias that exists in the data being propagated forward is very real and very meaningful."

Stratyfy is working with Underwriting for Racial Justice, a national working group convened by Beneficial State Foundation to drive greater fairness and access within BIPOC communities.

"That ends up being such a hard piece of really moving that racial wealth gap as it relates to availability of fairly priced credit," Kornhauser said. "So many lenders are so set in the way they've done things before."

Part of a broader issue

The racial wealth gap is part of an overall wealth gap in America. According to Advisorpedia, more than 70% of wealth in America is owned by 10% of families. The gap between the haves and the have nots isn't new, but it has been growing.

"When you look at 74% of Americans, according to our Inside the Wallet report, living paycheck to paycheck, you realize very quickly that it's just everybody you know," said Michael Woodhead, chief commercial officer of FinFit.

"Despite the best efforts of organizations like ours that are focused on financial wellness solutions and services, this problem's only gotten worse, and it was exacerbated by macroeconomics that came out of the pandemic," Woodhead said.

In his view, the financial services industry in this country has always been set up to serve people who have extra money at the end of the month, and they take that extra money and help them make it more money.

"As a result, if you don't have extra money at the end of the month, the financial services industry really doesn't have much to offer you," Woodhead said.

The way most Americans who are living paycheck to paycheck solve problems of lack of liquidity is with debt services that they can't afford, which creates even more problems, Woodhead said.

"But financially healthy people, even if they don't have savings to speak of, have access to affordable credit," Woodhead said.

FinFit works with employers to provide financial services to individuals who are underserved by the marketplace today, he said. It offers access to credit for emergencies or for long-term debt consolidation, with interest rates of 7.9% to 24.9%. Applicants don't need to have a FICO or VantageScore score, and instead, FinFit relies on a machine learning algorithm to price its loans.

The most important thing FinFit offers is an emergency savings solution, Woodhead said. "So the next time I have a financial emergency, I have an option: I could use credit, or I could use my own emergency savings account that I have built up over time," Woodhead said.

The traditional financial services industry has been paternalistic in telling people they're spending too much money — if they would just spend less than they make, they wouldn't have these problems, Woodhead said.

"That's the way we have tried as an industry to solve this problem for about 30 years: by shaking a finger at people," Woodhead said.

The cost of doing nothing

Banks that don't try to address the racial wealth gap face an existential threat, Tavares said.

"The demographics of our society are changing and technology has to keep pace in order for the lending system to continue to be resilient, growing, fair and free from risk," Tavares said. "What people don't often think about is there's a significant cost to not updating and innovating the technology for lending."

Some lenders hold that what worked 30 years ago or 20 years ago is tried and true and will continue to work today.

"There's actually a risk for that because in the America that we have today, the borrowers are not the same as 30 years ago," Tavares said. "And yet you're using this old, outdated technology, so there's a risk also of not innovating."

Many banks are making the decision to include more updated and inclusive technology because it's a business imperative in a country that's rapidly becoming majority-minority demographically, he said.

"If you look at a state like California, 58% of the population is Asian American, Hispanic American, and African American," Tavares said. "If you can't lend effectively to those people because you have outdated technology, that's a business problem, that's a profitability bottom line problem," he said.