Commercial developers could be the banking industry’s next big credit risk.

Many retailers, crippled by lower foot traffic tied to the coronavirus outbreak, didn’t pay their loans in May, with some banks reporting delinquency rates as high as 40%. If a similar percentage of stores are falling behind on their rent, it could create cash flow issues for landlords.

That might mean more bankruptcies, increased defaults on commercial real estate loans and greater stacks of soured loans for bankers to work through.

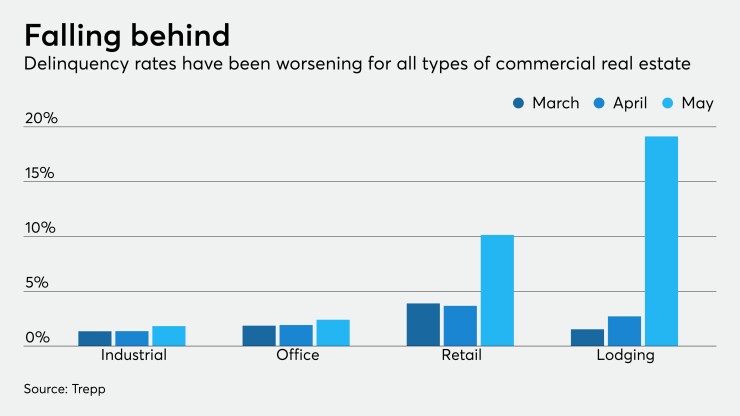

“We’ve seen problems rise dramatically already,” said Matthew Anderson, a bank and commercial real estate analyst at the data firm Trepp.

Trepp’s analysis of commercial mortgage-backed securities — an indicator of looming issues for banks — found that the CRE retail delinquency rate in May spiked by 647 basis points from a month earlier to 10.14%. More than 12.5% of retail loans were categorized as being in a grace period or more than 30 days delinquent.

“Those are staggering numbers,” Anderson said.

Corporate bankruptcies rose by 48% in May from a month earlier, with 724 businesses filing for Chapter 11 protection, according to data compiled by the legal-services firm Epiq Global. Bankruptcies had already risen by 30% during April.

Three prominent retailers — J. Crew, Neiman Marcus and JCPenney — were among the companies that filed for bankruptcy protection.

The numbers could have been even higher if not for filing delays due to the pandemic.

“We expect these delays to continue while key government programs address personal and commercial borrower liquidity concerns,” said Chris Kruse, a senior vice president at Epiq.

Heavy lifting expected

Bankers are watching the numbers closely as retailers of all sizes ask their landlords for rent leniency and renegotiated leases. Industry experts said deferrals, in many cases, are delaying problems that could intensify as the year wears on.

“We think the retail CRE asset class is climbing the ranks in terms of where folks are concerned” about nonperforming assets, the research team at Stephens wrote in a June report. Hotels and restaurants are struggling the most, but retail woes are deepening and “could create headaches down the road.”

Retail loans were 5.5% of total loans at banks in Stephens’s coverage universe. About 2.1% of those banks’ loans involve restaurants, and 3.6% are tied to hospitality.

Banks may face an uphill climb tackling issues with retail and commercial loans.

In April and May, banks extended loan terms, reduced interest rates and offered deferrals to give commercial borrowers time to get their arms around setbacks stemming from the pandemic.

As those short-term extensions near an end, bankers anticipate a second round of 30- to 60-day modifications, followed by deeper dives into loan books to determine which borrowers can recover as retailers reopen. The pandemic worsened issues in the retail sector, including shifting shopping patterns, a move to e-commerce and an excess of retail space.

Banks are hiring restructuring specialists, law firms and consultants to stress-test loans. They are shifting employees from commercial originations to foreclosure workout teams to analyze the conditions of each property and borrower.

“A lot of large retailers are not paying their rent, which is something that goes right [down] the chain,” said Harvey Rochman, a partner at the professional services firm Manatt. “Banks are recognizing that they’re going to have to take a much harder look at the business of the borrower" to determine "the best way to preserve the asset.”

The demise of malls, retail stores

As Marc Halle, a managing partner at Park Lane Investors, walked down Madison Avenue in New York this week he passed boarded-up retail stores where the only sign of life was a long line outside a Whole Foods grocery store.

“The whole retail world has been turned upside down,” said Halle, a former chief investment officer and head of real estate securities at PGIM Real Estate.

Halle, who estimated that 400 of the 1,000 malls in the United States will shutter in the next two years, said he is concerned that the demise of many smaller, regional malls will have a ripple effect on area economies and governments.

“What happens to those local communities?” he said. “How do they support their budgets and the municipal debt associated with that?”

Workouts should be different now because the Federal Reserve and five other regulators in late March

In a letter to the National League of Cities, the U.S. Conference of Mayors and the National Association of Governors, the acting comptroller of the currency,

“The consensus view is that the third quarter could get ugly, depending on governmental support and action,” said Walter Mix, head of the financial services practice at Berkeley Research Group and a former California banking commissioner.

“Senior bankers, workout people and bank lawyers who have been around the block all know that there’s a huge bet to kick the can down the road hoping that the economy is going to kick back in,” Mix added.

‘Plenty of triage to be done’

Banks are working through the painstaking process of screening their portfolios and categorizing loans to determine which are likely to be seriously impacted.

“There is plenty of triage to be done and the general thinking is that some large number of commercial tenants will not pay,” Rochman said.

While there is a sense that bankers want to help borrowers survive, Rochman said there are “significant limits” to what lenders will be willing to do — and for how long.

“This recession is really about commercial lending,” he said. “It’s going to take years to recover.”

Mark Zandi, an economist who runs Moody’s Analytics, estimated that 25 million jobs will be lost from peak to trough, affecting a third of the workforce.

Business reopenings and aggressive fiscal monetary policy have blunted the pandemic’s impact, but Zandi said he sees no obvious engine of growth going forward, and sees “massive consolidation” in the retail sector.

“Commercial real estate is in the crosshairs of this crisis,” Zandi said during