By basing credit decisions on artificial intelligence, Klarna made financing big-ticket purchases a cinch for shoppers. Now that the firm has received a banking license from Swedish regulators, it's time to seriously consider the broader industry implications of this kind of lending.

Klarna and companies like Affirm, Bread and Acima give online shoppers an instant loan to pay for a big-ticket item like a television or mattress.

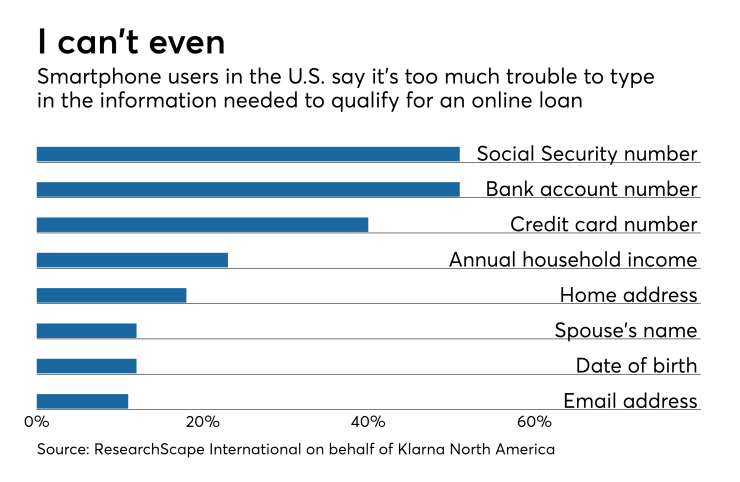

The customer types in very little information — in some cases, nothing more than a name and email address. No effort is required.

Behind the scenes, Klarna's underwriting software takes in data from more than 100 sources and uses artificial intelligence to make a credit decision in less than a tenth of a second.

“This is true disruption right at its heart,” said Alyson Clarke, principal analyst serving e-business and channel strategy professionals at Forrester.

Klarna has been offering checkout financing for more than a decade in Europe and two years in the U.S. It has 60 million consumers and 70,000 merchant partners in 18 markets. It has 3 million American customers.

Jim Lofgren, Klarna’s CEO for North America, theorizes that instant loans have become popular as a reaction against widely publicized card fraud and data breaches. Essentially, people are drawn to not having to surrender a bunch of information.

“When transacting online was becoming popular and the method of payment was still card-based and you saw a large amount of card fraud, people were still doubting their primary payment method, which was card,” Lofgren said. “We took the risk away from the merchants and we took the risk away from the consumer, so they could get the product, try it on and send it back if they didn’t like it.”

The widespread adoption of smartphones is also driving demand, Lofgren said, because card transactions are clunky on mobile devices.

“The phone is only this big and you don’t like the inconvenience of having to pull up the card and keypunch all those numbers in and verify everything every time you want to make a purchase,” Lofgren said. “Instant financing lends itself well to the smartphone environment.”

Aaron Allred, CEO of Acima Credit, a provider of instant leases at the point of sale, gives a lot of credit for the growing U.S. market in the U.S. to Affirm, a startup based here.

“Affirm has used technology to allow customers to buy anything and everything at the point of sale and pay for it over a period of time,” Allred said. “You could go to Delta.com and pay for your $700 plane ticket over a six-month period, and you can do that in two or three minutes — it’s almost as easy as checking out.”

Allred founded Acima Credit after he and his wife went to a local furniture store to buy their first couch as newlyweds, using the store’s financing. Three hours later they were approved and had their couch, but were frustrated at the hassle.

He saw opportunity.

“There was this insatiable demand out there in the marketplace for customers; they want this seamless POS option,” Allred said. “They want to be able to get finance in a matter of seconds, and because the tech has made it so fast and easy, this space has been exploding.”

Acima Credit works with several banks and is in talks with Wells Fargo for a large credit facility that Acima would use for its leases, Allred said. Wells Fargo would get some of the return, he said.

“Banks are either buying these fintech companies or they’re partnering with them. All the banks see what’s going on. They want in on this space.”

These firms have better technology than traditional lenders right, Clarke said, but traditional banks can catch up techwise.

“There’s a window of opportunity now to have that as a differentiator, but in a couple of years that window will close,” Clarke said. Traditional players could catch up by building their own version of the technology, buying it or partnering with a vendor or a fintech.

If the technology becomes equal, competition may come down to distribution, Clarke said.

“Once firms like Affirm and Klarna get embedded in a lot of retailers and they have that distribution footprint," she said, "they have an advantage in being there, in that line of sight when I’m making a purchase.”

The tech that makes it work

Lofgren calls Klarna’s credit issuing platform the “secret sauce of what we do.”

It takes into account more than 180 creditworthiness variables.

“It goes significantly deeper and wider than the traditional FICO, which normally lenders would look heavily at,” Lofgren said. It looks at “what you’re buying, at what time of day you’re buying, what IP address you’re coming from, and a bunch of other variables.” These factors are analyzed for each market and industry.

“Because we’ve been doing this since 2005, we’ve come to a point now where we can do a credit decision in less than 0.4 seconds,” Lofgren said. “People are impatient, and you want to remove as much friction as you can from the purchase process, and you want to have a decision really fast.”

The way Klarna verifies borrowers’ identities varies by market.

A big part of what it uses is behavioral data — a young parent buying diapers at 3 a.m. is a low risk.

“There’s also external data we leverage, and that might be different from market to market, depending on what’s available to match your address to where you say you live and what’s on file and where the item is going, for example if it’s being shipped somewhere,” Lofgren said.

Who are the customers?

Much of online lending is dominated by those pursuing customers too risky for traditional banks.

But that’s not always the case. Companies like Affirm and Klarna go after prime customers. These users can get potentially lower interest rates than they would from their bank or card company. Some like the idea of using a loan purely for one purchase — once it’s paid off, it’s done.

In a study of more than 2,000 consumers conducted by Researchscape and sponsored by Klarna North America, 47% said that when shopping online, they would like to be presented with the option of instant financing.

These providers are tapping an unmet need, especially among younger people, Clarke said.

“You have young millennials coming through who are loaded with student debt, not wanting to make the same mistakes their parents made around debt, and perhaps a little nervous about taking on debt after the financial crisis,” Clarke said.

Acima does target the subprime consumer — the person who needs a mattress but has a poor credit score and therefore can’t qualify for a loan from a prime lender. It offers leases rather than loans and it does so through a simple process on a smartphone.

It built a technology backbone that gathers and verifies information from credit bureaus and other data providers and gathers thousands of data points on each consumer. For instance, one provider checks the device ID for each applicant to see if there has ever been fraud associated with the device. Another alternative credit bureau checks for past fraud reported on the consumer.

Then the platform has to be able to make a prudent credit decision in a matter of seconds and enable the merchant to be paid “in a manner that doesn’t cause any more brain damage than swiping a Visa or Mastercard,” Allred said. Acima funds the leases through its balance sheet, so merchants are paid within 24 hours.

Customers can lease to own merchandise, or lease and return items. Repossession is handled on a case by case basis. Acima says it works with each customer to help them pay off the money owed, however possible. Nine out of 10 people using lease-to-own services like this one do end up paying it off, according to Acima research.

Why Klarna is becoming a bank

Klarna is becoming a bank to better compete with banks.

“Without the banking license we can’t offer all the services that banks can,” Lofgren said. “For us to really disrupt the industry, which is what we have been doing for a lot of our merchants and consumers for a long time in Europe and in the last two years in the U.S., we need that.”

Today, the company funds its business through deposits it takes from German and Swedish consumers through third-party banks.

“With a banking license, we can offer that directly to consumers,” Lofgren said. “We have a history of serving consumers really well. We want to take our DNA into the banking industry and make sure we disrupt it entirely.”

Lofgren couldn’t or wouldn’t say which products Klarna might start offering in the U.S., where it provides loans through Salt Lake City-based WebBank. He said the company is not currently pursuing a banking charter in the U.S. but declined to say what the firm might do in the future.

“There are a number of different things we can do, there are other things alluded to in the press such as credit card issuing and debit card issuing,” Lofgren said. A recent partnership with Visa spurred some of that speculation. “We’re exploring a number of different avenues, different products we’ll go to market, or even a combination of a few different products. Right now we can’t confirm anything, because we’re in an early mode.”

Future of the model

Clarke said she worries that some of the checkout financing models haven’t been tested in a market downturn.

For instance, some purchase financing firms offer promotions that customers mistakenly think are free, Clarke said.

“But the business model relies on a lot of these customers not paying off in time and getting hit with penalty rates after the interest rate period,” she said. Their rates could end up being higher than a credit card or a personal line from a bank.

“That sort of stuff can be dangerous in an economic downturn when people are defaulting,” Clarke said. “It should start to catch the attention of the regulators, because if they’re preying on subprime consumers who are likely to not pay in three months and are paying higher interest rates than credit cards, to me this starts to look and feel not so good, and maybe even start to be a little like payday lending.”

The fintechs will have to be careful about their underwriting, Clarke said.

“What the danger is and where the risk is, is the risk models underneath,” she said. “If you’re able to get full data on customers digitally and bring all that into underwriting immediately, the technology is only as good as your underwriting models underneath. I would argue that these new players may not survive an economic downturn because of their underwriting models.”

Editor at Large Penny Crosman welcomes feedback at