One of the most beloved features of Simple, the neobank that Madrid-based BBVA bought in 2014 and then

Simple trademarked the name Safe to Spend and aggressively protected it. In 2015, it sent a cease-and-desist letter to Mondo, the U.K. neobank that was using the name on its app at the time. That may be one reason why this feature, the loss of which many Simple users lamented on Reddit and Twitter, is hard to find. But a few fintechs, such as Digit, are emulating that service.

More banks and fintechs might want to do the same.

“It does behoove others to pay attention” to what Simple did with Safe to Spend, said Mark Schwanhausser, director of digital banking at Javelin Strategy & Research.

“Savings has turned into one of the hot topics of 2021,” Schwanhausser said. “That's partly because there's a growing importance in trying to provide better financial wellness and financial fitness. The banks and fintechs are all trying different approaches to that. Some are focused on saving. Some are focused on spending, some on credit scores.”

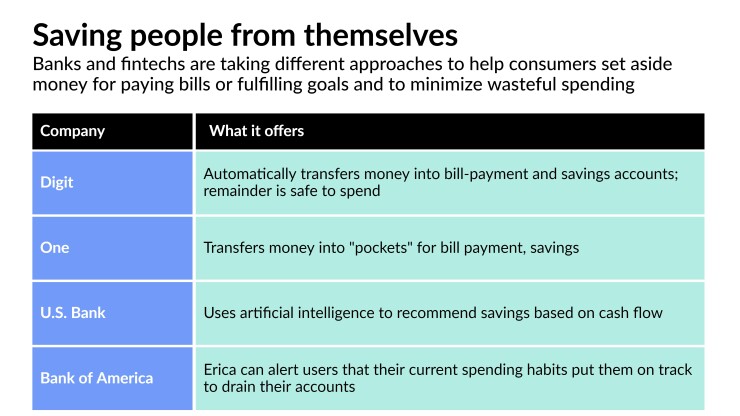

The main difference between fintechs' and banks' approach, in Schwanhausser’s view, is fintechs are trying to turn this kind of help into an automated service.

The fintechs say “we're going to be proactive and guide you to save money,” he said. “Banks are struggling to make the leap from providing do-it-yourself tools for self-aware customers to addressing the majority of consumers who care about their money but may not know where to begin.”

What Digit is doing

San Francisco-based Digit, the fintech that pioneered the use of artificial intelligence to help consumers frequently save small amounts of money without hindering their ability to pay bills and handle living expenses, recently introduced its own version of Safe to Spend. At the same time, Digit debuted a full-fledged bank account called Direct with the $9.8 billion-asset MetaBank, which is based in Sioux Falls, South Dakota.

In recent years Digit has launched other related features like the ability to automatically pay off credit card and student loan debt in safe increments. It has also increased its monthly fee to $9.99.

“We really think about how do you make managing your money easier day-to-day, and how do you make it easier to be financially healthy?” said Ethan Bloch, Digit’s CEO. “We're trying to help you budget for your bills. And on the flip side of that coin, we're trying to help make it really easy to control your spending.”

When customers use Digit’s safe-to-spend feature, each time a deposit hits the Digit account, some of that money is automatically transferred to an account allocated to paying bills. Another portion is shifted to a savings account.

Digit displays the amount that’s left over, or “what you could be spending right now without putting your bills in jeopardy,” Bloch said.

Digit recalibrates this safe-to-spend amount each night while the user is sleeping.

“It will auto-tune and make little adjustments, giving somebody a little more money for bills or a little more for savings,” Bloch said. “It’s not going to make huge money movements, but it will make some smaller adjustments and at 9 a.m., you'll get a notification that tells you how much is in your spending and how much Digit has set aside for bills. So you're starting each day with some sense of the ground truth of your money.”

The new feature stemmed from customers asking Digit to help them budget better for their bills, as well as save more and control their own spending.

It took Digit 18 months to build this out, Bloch said. The hardest part was creating its own bank account and choosing Metabank as its bank partner and Galileo (now part of SoFi) as its processor.

To make the new feature work, Digit sets up three bank accounts for every Digit Direct account: a checking account, a savings account and a spending account. The spending account is attached to the Digit debit card.

“We weren't just building the vanilla neobank with a debit card,” Bloch said. “Direct has technically three accounts that underpin it and money moves between all of them instantly.”

This way, Digit saves customers from themselves: They can’t accidentally spend money that they didn't intend to.

“We’re adding just a tiny bit of friction, because I might want to spend the money,” Bloch said. “But if I have to go into the app and transfer $30 out of the Bills account into the Spend account, that little bit of friction makes me realize, by doing this, I'm going to be less likely to be able to pay my rent this month. Is that OK? We’re hearing that that little tiny bit of friction built into the experience is really helpful. We're designing a car with seat belts and airbags because we know people get in accidents.”

You Need A Budget, a fintech based in Lehi, Utah, provides a budgeting app that shows users how much money they have available to spend after upcoming bills, savings allocations and living expenses are accounted for.

Not everyone's a fan

Critics question the efficacy of safe-to-spend programs.

“Safe to Spend is a pretty common concept, and can be useful, but it is often not used by customers as much as it is in marketing,” said Brian Hamilton, founder and CEO of the challenger bank One, which is based in Sacramento, California. “The algorithms are useful when they're accurate and recurring bills are reliable and all connected and everything works exactly right.”

If there are any disconnects or inaccuracies, people won’t trust the safe-to-spend number, rendering it useless, he said.

One offers “pockets” for budgeting for specific expense categories that can be taken out of each paycheck or directly debited by each biller.

Many fintechs and banks use this concept of pockets, envelopes or buckets to help people manage their money, Schwanhausser pointed out. One envelope will be for rent, another for saving for vacation, and so on.

“The human brain often feels more comfortable when it can compartmentalize,” Schwanhausser said. “So you're seeing players like Chime, One, Stash, Varo and others playing with different variations of buckets.”

Hamilton isn’t completely opposed to the idea of Safe to Spend.

“Safe to Spend, when done right, is a valuable concept,” he said. “We will likely employ some similar projections in our product but in a slightly different form based on user feedback on what they find most useful.”

Schwanhausser is also skeptical about safe-to-spend programs.

“With safe to spend, it's often about saying, we started with your paycheck, we took out your bills, we took out the things you've encumbered yourself with, we took out your spending,” Schwanhausser said. “And then we looked through the sofa cushions, and we found what was leftover. And that becomes your safe to spend.”

It would be better to flip that around and save first: 10% goes into savings, and you live on the other 90%, he said.

Banks stay savings-centric

This is what some banks have done, Schwanhausser said: Help people manage their cash flow by emphasizing savings.

Some go for the roundup or Keep the Change approach that Bank of America pioneered in 2005. As the name suggests, when a customer makes a purchase, the amount is rounded up to the next dollar and the leftover change is swept into a savings account. Some let people set their own rules, for instance, by depositing a portion of each paycheck automatically into a savings account.

U.S. Bank’s Pay Yourself First program, which it created with Personetics and launched in March, uses AI to identify ways customers can save. It offers recommendations based on their personalized cash-flow patterns.

Automatically saving a portion of each paycheck is far more effective than any keep-the-change program, in Schwanhausser’s view. A person in a roundup program might save $13,000 over the course of 15 years, he said. But if that same person saved 10% of income, the savings would be $130,000.

“You have fundamentally changed that conversation in a way that's going to lead to that $130,000 savings after 15 years,” he said.

The fintechs’ what’s-left-in-the-sofa-cushions approach works best for a younger consumer who hasn't yet gotten into overspending habits, Schwanhausser said.

But the biggest difference between banks and fintechs, he said, is in the types of tools they offer.

“The banks see it as a bunch of tools: You figure it out,” he said. ”The fintechs are trying to say, we're going to hold your hand and guide you. And I highly commend that. That can lead into the use of personalization, notifications, gamifications, things that take a consumer deeper into what should I be thinking about? What should I prioritize? What should I save for first? The fintechs are treating it almost like it's an advice-driven relationship: We're going to help you move forward. Banks are in a transactional relationship, and they're saying here's some tools for you to figure it out.”

Banks are not helping people figure out how much money they will have after their scheduled bill payments have been made.

“Help me do the mental math — we're not even seeing banks do that stuff, which is completely within their realm,” Schwanhausser said.