Are credit default swaps harmful to consumers and society at large?

The Vatican reignited a debate on the topic recently when it

Regarding credit default swaps, it said "the spread of such a kind of contract without proper limits has encouraged the growth of a finance of chance, and of gambling on the failure of others, which is unacceptable from the ethical point of view."

But the Commodity Futures Trading Commission

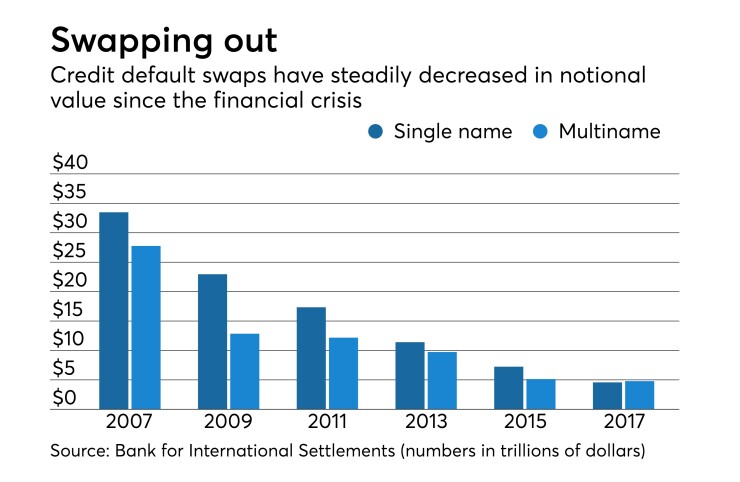

Although credit default swaps have declined markedly since the days of the financial crisis, the exchange was proof that there remains lingering distrust of them among the public at large.

The crisis helped give CDS a bad rap. AIG Financial Products wrote credit default swaps on more than $500 billion of assets, including $78 billion on collateralized debt obligations. When the CDOs lost value as the underlying mortgages collapsed, AIG had to be bailed out when the financial crisis hit. (Curiously, the Vatican did not mention CDOs, the debt instruments that were used to bundle trillions of dollars worth of subprime mortgages into triple-A-rated investments, in its document.)

In its letter defending credit default swaps, the CFTC said derivatives allow the risks of variable production costs, such as the price of raw materials, energy, foreign currency and interest rates, to be transferred from those who cannot afford them to those who can. For instance, farmers can hedge against their crops.

“Derivative products allow farmers and ranchers to hedge production costs and delivery prices,” wrote the CFTC, which is chaired by Chris Giancarlo, a practicing Roman Catholic. “They are the reason shoppers enjoy stable prices, not only in the supermarket, but in all manner of consumer finance from auto loans to household purchases. Derivatives markets influence the price and availability of heating in homes, energy used in factories, interest rates borrowers pay on home mortgages, and returns workers earn on retirement savings. In short, derivatives stabilize the cost of day-to-day living.”

Steve Rubinow, former chief information officer of the New York Stock Exchange and current director of the Institute for Professional Development at the College of Computing and Digital Media at DePaul University, where he teaches classes on ethics in technology, finance and medicine, said the trouble with credit default swaps and other sophisticated financial instruments is that they are not well understood by most people, and some may not realize they have exposure to them.

If there were a credit default swaps crisis, “a lot of people would be hurt, some severely, and leaving them exposed like that, is that an ethical thing to do?” Rubinow said. “I would say it’s a hard question to answer because those financial instruments serve a purpose: They help facilitate the credit markets.”

Kevin McPartland, head of market structure and technology research at Greenwich Associates, argues that the credit market needs more derivative exposure, not less.

“Increasingly, bond investors are using ETFs" — exchange-traded funds — "to get exposure because they don’t have access to liquid derivative markets like they do for interest rates,” he said. “That’s a negative for the credit market.”

He also noted that investors in credit default swaps tend to be large hedge funds.

“There’s an assumed level of institutional knowledge,” McPartland said. “There are also a lot more controls in place around disclosures and documentation and risk standards. Even the end investors in those funds are looking for a lot more transparency than they have before, right down to understanding which rating agency is being used, what model are they using and what are the inputs?”

Is the use of algorithmic pricing dangerous?

The Vatican also appeared to indict the practice of algorithmically pricing complex derivatives. Its document pointed out that for some types of derivatives, “more and more complex structures were built (securitizations of securitizations) in which it is increasingly difficult, and after many of these transactions almost impossible, to stabilize in a reasonable and fair manner their fundamental value. This means that every passage in the trade of these shares, beyond the will of the parties, effects in fact a distortion of the actual value of the risk from that which the instrument must defend. All these have encouraged the rising of speculative bubbles, which have been the important contributive cause of the recent financial crisis.”

Algorithmic models make it possible to price and assess risk for credit default swaps and collateralized debt obligations, and therefore make them sellable in a way that until now would have been impossible. But the models obviously didn't predict the financial crisis.

Some observers argue that the Vatican has a point, considering the opaqueness of the models.

“Financial models are so sophisticated that to unpeel the onion is a hard thing to do; it’s constantly changing and it takes a sophisticated reader of the model even to understand what they’re looking at,” Rubinow said. “The transparency is not there. It’s not available for everyone to understand in a way that would make it completely safe. You have to explain to people how the models and pricing work, what the downside could be.”

Is there a need for more regulation to bring ethics to financial services?

The Vatican stated in its document: “The recent financial crisis might have provided the occasion to develop a new economy, more attentive to ethical principles, and a new regulation of financial activities that would neutralise predatory and speculative tendencies and acknowledge the value of the actual economy. Although there have been many positive efforts at various levels which should be recognized and appreciated, there does not seem to be any inclination to rethink the obsolete criteria that continue to govern the world."

McPartland argued for “measured and thoughtful” regulation.

“After the crisis and the implementation of Dodd-Frank, there was this political rush to write and implement new rules, and have the market adopt them,” he said. “It forced things to move more quickly than they should have — to some extent, understandably so. The economy had gone through a tough time, so everybody was in a hurry to feel like they were putting in place something to stop it from happening again.”

Now there’s less of a hurry, and rules could be rewritten to be less prescriptive and a more principles-based, McPartland said.

But some questioned the Vatican's authority to question such issues, considering its own ethical scandals in recent years. The church's net worth exceeds $200 billion, and some have raised concerns whether it has adequately used that wealth to help the underserved.

“It feels like they should stick to their business and finance will stick to its,” McPartland said.

Others say the church should speak up.

“The church has more than a right,” said Bradley Leimer, co-founder of the consulting firm Unconventional Ventures and managing director and head of fintech strategy at Explorer Advisory & Capital. “Sometimes it can come off as sanctimonious, because they have the opportunity to do so much with their wealth. How can you preach when you as an entity have been collecting riches for millennia?”

The church could lead by example, Leimer said, by offering low-cost banking to those less fortunate.

“If they want to talk that talk and suggest to other industries they could be doing more, then they need to ramp up their efforts in the space,” he said. “Because they could be a force for good in so many countries that need it. They could take that criticism and show the industry how it could be done.”

Editor at Large Penny Crosman welcomes feedback at