The credit binge has been over for years, but the real hangover starts in 2010 for banks holding a lot of commercial real estate loans.

During the easy lending days of 2005 to 2008, banks extended a wave of such loans to retailers, office building owners, hotels and other businesses. But business profits have plummeted since then, and with vacancy rates soaring and rents falling, real estate values have plunged as well.

Refinancing and retiring these credits could be a nightmare; a majority of loans due through 2014 may be underwater, industry experts say, meaning more banks will be forced to restructure loans to avoid costly foreclosures.

"For a lot of community and regional banks that have a concentration in real estate, it's gotta be problem No. 1," said Matthew Anderson, a partner with Foresight Analytics LLC, a market research firm in Oakland, Calif. "For the largest banks, actually, commercial real estate isn't as big an exposure as consumer lending. But for a lot of those regional and community banks, commercial real estate is their main focus. At a minimum, it's going to be a drag on earnings."

U.S. banks had a historic $1.3 trillion of commercial mortgages outstanding as of Sept. 30, with about $60.5 billion of them delinquent, Foresight estimated.

About $650 billion in banks' boom-time CRE loans are coming due over the next four years, with more than $150 billion maturing in 2010. About 43% of the loans due next year exceed the current value of the properties they cover, Foresight said. The percentage of underwater loans due in 2011 is 60%, and the figure rises for each year thereafter.

"Everyone's view is pretty much consistent on this: there are significant numbers of commercial mortgage loans that are underwater because real estate property values have dropped significantly," said Robert Gordon, a partner at the law firm Mayer Brown LLP. "Even for loans that are performing on a cash-flow basis, when they hit maturity, it is going to be difficult to refinance them without additional equity."

But is CRE due for a meltdown akin to the home mortgage crisis? Market watchers have been describing CRE as the proverbial next shoe to drop in the credit crisis for at least a year now. Gordon and others say that may be overblown, though banks are certainly in for a period of extended pain.

"Everything is dependent on the economy and how quickly do we see a recovery taking place," said Keith Leggett, the senior economist at the American Bankers Association. "That will be a key factor affecting the commercial real estate market. Because [when] you have high levels of unemployment, you're probably also going to see higher vacancy rates. This is going to put pressure on rents."

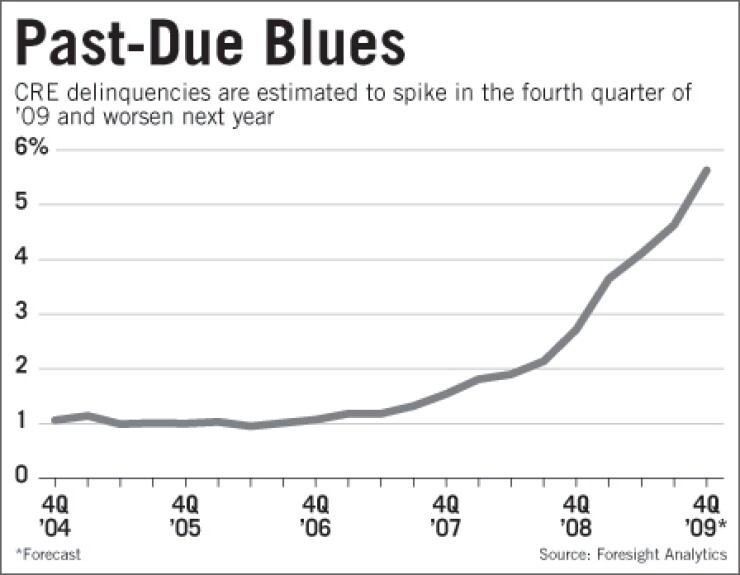

CRE stress is already doing plenty of damage. It's been a key factor at a number of the 140 banks that had failed in this cycle through Monday. Though CRE losses have not been as severe as losses on construction and development credits, they are accelerating. The CRE delinquency rate of 4.63% at Sept. 30 was up from 4.1% in the prior quarter and 2.1% a year earlier, according to Foresight. It could spike to 5.6% for the last three months of the year.

While a full-blown CRE crisis is conceivable, the more likely scenario is that small and midsize banks are just beginning a long slog through billions of dollars in commercial real estate losses. Helping banks avoid the worst: CRE loans are not all coming due at the same time, and the loans that are the deepest underwater — issued at the credit bubble's peak — do not mature for another couple of years. CRE loans tend to have a lifetime of five years or more.

"A lot of our deals were done on 10-year maturities, with five-year price resets," said Steve Rice, executive vice president of commercial banking with Umpqua Holdings Corp. in Portland, Ore. "The greater challenge for the entire market and entire industry is when the hard maturities come due."

Catherine Mealor, a banking analyst with KBW Inc.'s Keefe, Bruyette & Woods Inc., noted that with CRE loans tending to carry longer-dated maturities than other kinds of commercial loans, banks have more time to grow earnings and cover their CRE losses.

And the favorable terms borrowers got at the height of the credit boom mean it is relatively easy for them to keep making interest payments, even if retiring the loan is an issue.

"Losses will come, but the burn will be slow," Richard Ramsden, an analyst with Goldman Sachs & Co., said in a CRE research note earlier this year. "Commercial mortgages will be an issue, but given the cash flow on the properties coupled with a zero-interest rate environment, banks can deal with the issue slowly as there is debt service coverage flexibility" even if the borrowers' properties "are way underwater."

That means borrowers can stay solvent as long as they do not have to retire the loan. Recognizing this, regional lenders like Susquehanna Bancshares Inc. in Lititz, Pa., and Umpqua have been giving more extensions and other concessions to worthy commercial borrowers that have fallen on hard times. The trend should accelerate after regulators issued a policy statement in October that essentially gave banks their blessing to work out loans with borrowers that are earning money and making payments, even if their properties are underwater.

Whether this guidance is good for the industry remains a subject of debate.

Supporters of workouts say they let banks stave off losses while building goodwill with borrowers that have the potential to survive the recession. They also buy time for lenders to improve earnings and raise more capital to absorb future losses.

Detractors say workouts can be abused to mask banks' true health and may draw out the downturn by enabling lenders to "extend and pretend." Mealor said the flexibility regulators have granted banks comes with a price: They will keep a closer eye on CRE books, and may require bankers to raise reserves to cover troubled loans, even if the bankers avoid having to charge them off.

"It's kind of a race against time," Anderson said. "Whether the economic recovery is strong enough or fast enough to prop up the commercial real estate [market] remains to be seen."