WASHINGTON — Bankers are generally happy with the House Republican tax plan released last week, but one provision of the proposed overhaul is likely to give them pause: a cutback in the deduction for deposit insurance premiums.

The tax reform proposal did not include a "bank tax" per se, but the reduction in Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. assessments that can be deducted as a business expense — including eliminating the deduction altogether for banks with over $50 billion in assets — is seen as a definite drawback in a plan the industry is hailing for the most part.

"The just-introduced tax reform legislation can be fairly characterized as the ‘screw the big banks, again’ provision,” said Bert Ely, a bank consultant in Alexandria, Va.

The GOP plan estimated that restricting the FDIC-related deduction would result in $13.7 billion in revenue for federal coffers from 2018 through 2027. Banks between $10 and $50 billion in assets would see a gradual decrease in what they could deduct, while the plan would not affect the deduction for banks with less than $10 billion.

If the plan is enacted, it would not be the first time lawmakers have looked to big banks to help pay for legislation not specifically tied to financial services. The 2015 Fixing America’s Surface Transportation Act included a measure to cut banks' Federal Reserve dividend to raise money for the highway trust fund.

The tax plan provision "is comparable in its intent to the FAST Act,” Ely said.

However, while the restriction on the deduction for premiums has drawn industry concerns, the criticism has seemed muted, with industry representatives appearing to take a holistic view that the tax plan is still a win overall — particularly if it makes good on a proposal to lower the overall corporate tax rate.

“The 20% rate for corporations in particular promises to generate economic activity and jobs that will benefit the country and our customers,” American Bankers Association President and Chief Executive Rob Nichols said in a statement. He added, “We are encouraged by our initial analysis” of the plan.

Howard Headlee, president and CEO of the Utah Bankers Association, said the plan has enough benefits for banks potentially to look beyond a smaller deduction for FDIC premiums.

"Real FDIC-insured banks have always demonstrated a commitment to doing what is best for the country," Headlee said. "Tax reform is so important, we are trying hard not to focus exclusively on our own interests and stay focused on the broader benefits of the plan."

Still, in his statement, Nichols noted, “We are concerned that the House bill proposes to change the rules for deducting the cost of FDIC premiums for some banks.”

Chris Cole, executive vice president and senior regulatory counsel for the Independent Community Bankers of America, said the group would like to see the measure pulled from the tax proposal.

“There is an exemption for banks under $10 billion which covers most of our members, but we still oppose it because we know it is only a matter of time before that exemption will be reviewed again and we will lose it,” Cole said.

Some analysts framed the proposed measure as a toned-down version of a bank tax.

"Though the dreaded bank tax wasn’t included, the plan has a mini-me bank levy," said Charles Gabriel, an analyst at Capital Alpha Partners, in a note to clients, although he noted that the $13.7 billion in estimated revenue was a far cry from the $80 billion estimated from a previous proposal to impose a surcharge on "systemically important financial institutions."

The tax plan comes at a time when bigger banks are already paying more in FDIC assessments to boost the Deposit Insurance Fund as part of a plan to restore the agency's insurance reserves, which had suffered mightily in the financial crisis.

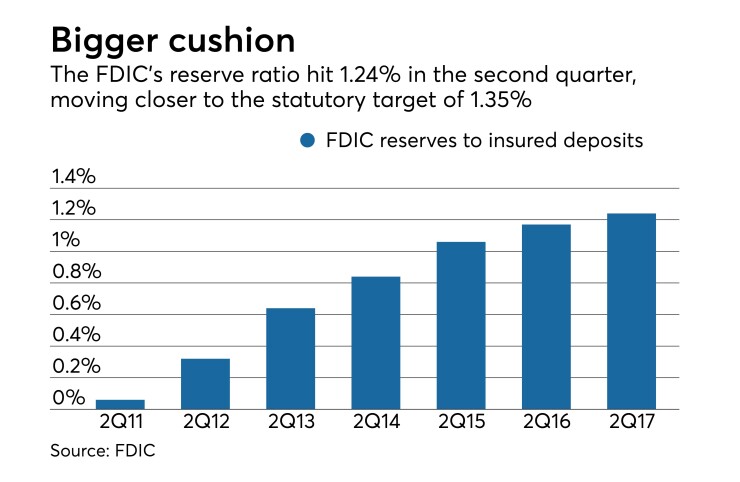

After the fund dipped into the red, the Dodd-Frank Act increased the minimum ratio of reserves to deposits from 1.15% to 1.35%, a target the FDIC must reach by 2020. The ratio stood at 1.24% as of June, according to the latest FDIC update.

As part of the restoration plan, ever since the reserve ratio crossed over 1.15%, banks with more than $10 billion in assets have been paying an additional surcharge to get it the rest of the way. The FDIC has expressed a desire to increase the reserve ratio even higher than 1.35%, which could worsen banks' concerns if they lose their ability to write off the assessments from their tax bill.

“The point where [the FDIC] reaches 1.35, when they are going over that, I think the conversation will be different,” Cole said.

Ely noted that the House GOP projections may overstate how much the FDIC plans to raise.

“The premium amounts projected by the Ways and Means Committee seem far in excess of what the FDIC needs to collect in order to reach the reserve-target ratios set for it by Congress unless the committee is anticipating a very costly round of banks failures in the coming years,” Ely said.

Cole said taking away the deduction could worsen problems for struggling banks.

“For banks that are on the margins … a bank that has gotten a low Camels score for some reason or another and they see their premiums jump, that‘s exactly the situation when their earnings are low and everything is bad and to lose the tax deduction as well, that is just another hit to them,” he said. “For banks on the margin I think it will be a problem.”

But the ultimate effect of cutting back the FDIC-related deduction may be limited, according to some analysts.

An analysis of the tax reform proposal by Keefe, Bruyette & Woods said that current annual FDIC assessments average only 4 basis points of assets for most large banks on a pretax basis.

"This is a fairly modest partial offset to the reduction in the tax rate for large banks," the KBW proposal said. "The change in the deductibility of FDIC premiums is not exactly a 'bank tax,' which we had previously cited as a potential risk to banks, but it is consistent with our forecast that some benefits that larger banks might see from lower tax rates could be slightly offset elsewhere in the plan."