For investors looking to dun banks over poorly underwritten mortgage-backed securities, a flurry of government subpoenas may help guide the way.

On Monday, the Federal Housing Finance Agency said that, as the conservator of Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae, it is subpoenaing loan-level underwriting and performance data from 64 security issuers and other entities. The agency said its goal is to "determine whether [private-label securities] issuers and others are liable" for losses on the two government-sponsored enterprises' investment portfolios.

The FHFA's request could be a tentative step toward filing a lawsuit akin to those of the Federal Home Loan banks and hedge funds, which seek to force a gamut of banks to repurchase deteriorating mortgage-backed securities. But because of the GSEs' gigantic portfolios and their federal conservator's ability to demand documents outside of court, the subpoenas pose a significant long-range threat to the as-yet-unnamed entities being served.

The conservator "is asking for the loan-level data that we ultimately want to get in discovery," said Owen Cyrulnik, a partner at the law firm of Grais & Ellsworth who represents the San Francisco and Seattle Home Loan banks in their suits. The FHFA "is able to take a leap over the normal litigation process, and get much further, much faster."

"Fast" is a relative term in such disputes, which will likely drag on for years. But other observers said that the breadth of the FHFA's inquiry could potentially change the landscape for MBS litigation. Though the bulk of the FHFA's subpoenas deal with underwriting, the agency explicitly mentioned servicing as an area of inquiry as well.

Ken Kohler, a partner in Morrison & Foerster's banking practice, said the large number of entities receiving subpoenas likely includes "just about everybody" in the field and represents a "shift in the balance of power between the investor and the issuer."

The scope of the issues the FHFA is looking at also appears to exceed that of prior private-label MBS litigation suits, said Paul Noring of Navigant Consulting.

The agency's press release explicitly cites the servicing of loans as an area of interest.

"This is now a government action, and it appears to go beyond initial underwriting," Noring said.

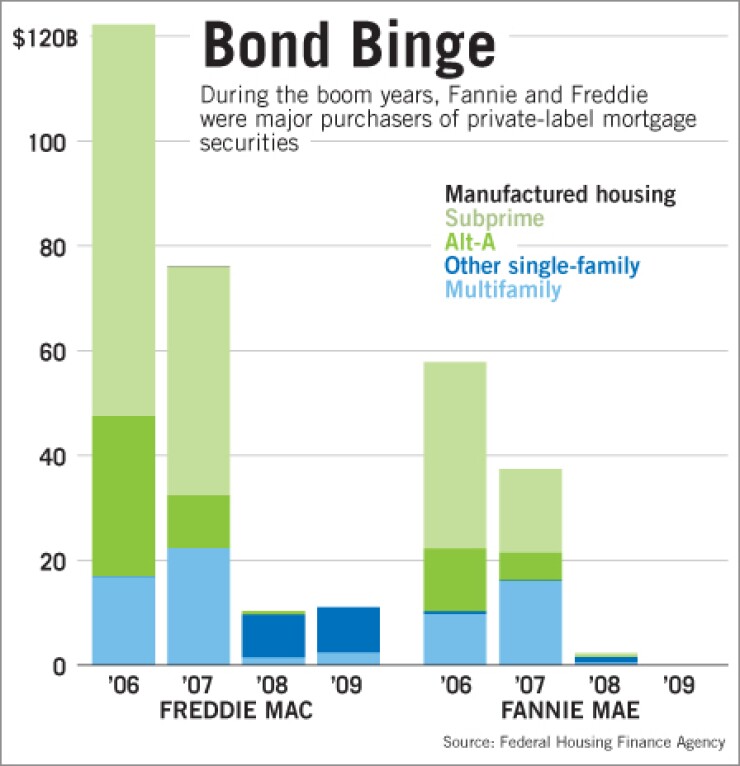

The FHFA explicitly said the subpoenas are "a financial inquiry, not an investigation or a lawsuit," but the potential scale of any attempt by the agency to force mortgage-backed securities on their underwriters would likely dwarf outstanding lawsuits. At the beginning of the year, Freddie alone held more $100 billion of bonds backed by subprime, alternative-A, option adjustable-rate and other nonagency mortgages.

Neither GSE has revealed identifying information for specific securities in their portfolios, and both invested solely in what were originally investment-grade securities. But information on the current ratings and losses severities of the securities suggests the losses are disastrous. Average delinquency in Freddie's $62 billion subprime residential mortgage-backed security portfolio is above 50% for the years between 2005 and 2008, with an average loss severity of around 70%. Freddie's gross unrealized losses on subprime alone have already hit $21 billion, and more than 80% of the securities have fallen below investment-grade.

Though Freddie and Fannie's problems are by no means limited to their investment portfolios, the GSEs failed as a direct result of residential MBS losses, the FHFA's acting director, Edward DeMarco, told Congress this spring.

"Investments in private-label MBS were primarily responsible for eliminating Freddie Mac's preconservatorship net worth of $27 billion and played a significant role in the initial draws under the Preferred Stock Purchase Agreements," he wrote in a letter to senior banking committee members in both houses of Congress.

Were the FHFA to try to recoup Fannie and Freddie's losses, the agency said Monday, whatever money was recovered would go toward offsetting the Treasury's continuing GSE bailout.

But getting direct compensation for taxpayers would require clearing the same hurdles that the lawsuits filed by the Home Loan banks and hedge funds face.

"Clearly there was poor underwriting," said Brian Harris, a senior vice president at Moody's Investors Service. "Does that rise to a legal issue is a different question."

If the FHFA were to make a case, it would have to demonstrate that the securities it bought contained collateral that was materially different from what was promised in the securities' prospectuses and other documentation. That would require disentangling losses due to sloppy or fraudulent underwriting from "a 35% decline in house prices nationwide," Harris said.

Such a lawsuit over origination accuracy would closely resemble the suits already filed by the Federal Home Loan banks and other investors.

But the FHFA's conspicuous inclusion of "servicing" as a topic of interest raises the prospect that the agency may be looking at how banks managed the repurchase and collection of delinquent loans as well, Noring said.

That avenue is largely untried, he said. The basis for a possible suit would likely be that mortgage servicers failed to properly manage the collateral after the securities' sale.

Servicers' obligations vary, but investors could argue that a defendant failed to buy back mortgages that go into early delinquency or to pursue adequate loss mitigation efforts.

Whether the FHFA's inquiry will be of use to other litigants, Noring and others said, depends on how the FHFA uses the information it obtains.

"They can directly get their hands on documents, and be in a far better position to take action," Kohler said. "They have a leverage that an ordinary private-label investor wouldn't have."