CINCINNATI - For all of the acquisition deals Fifth Third Bancorp has made under chief executive George A. Schaefer Jr., he says he can recall only one instance where he had the tables apparently turned on him.

The approach came in the form of a letter inquiring about the possibility of acquiring "the company's operations," he recalls. Follow-up calls revealed that offer to be a case of garbled language: a banker's attempt to express interest in some branches.

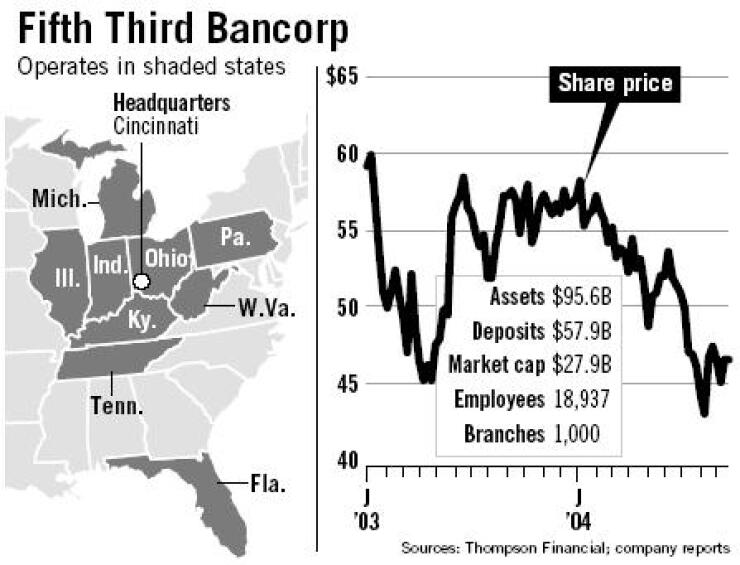

Mr. Schaefer says he doubts he will ever actually face the question of whether to sell Fifth Third. In his view, its tight-run operations - an efficiency ratio of 48.9%, compared with the industry average of 58.5% - makes it nearly impossible for any buyer to justify paying the premium a takeover would require.

He then pulls out his pencil - assuming a premium of 30% to Fifth Third's roughly $30 billion market capitalization, a buyer would have to pay about $40 billion. The buyer would then want to achieve a 15% to 20% return, or annual profits of $6 billion to $8 billion, on Fifth Third's operations, Mr. Schaefer says. But his company expects to post earnings of about $1.8 billion for this year.

A buyer "would have to triple or quadruple our earnings," he says. "If you are an investor, is that a good play? You probably say, 'Hey, no, I don't want to pay. I'll go and find something bad to fix up.' "

For years Mr. Schaefer and his management team won praise for their relentless focus on costs and their ability to grow through acquisitions.

But some of that luster faded after Fifth Third's 2001 acquisition of Old Kent Financial Corp. of Grand Rapids, Mich., for $4.9 billion, then its largest acquisition ever. Fifth Third never got around to expanding its back-office operations to accommodate the much larger and more complex operations.

In September 2002 it disclosed that it had detected a mistake in the booking of certain securities transactions, forcing it to take a $54 million charge.

Two months later it revealed that Ohio regulators and the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland imposed a moratorium on acquisitions, including its pending one of Franklin Financial Corp. of Nashville.

The error triggered criticism of a much larger issue: Fifth Third's risk management and controls. In March 2003 it signed an agreement with the Cleveland Fed and the Ohio Division of Financial Institutions that said, among other things, that Fifth Third was not in compliance with the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act's financial holding company requirements.

To the surprise of virtually all observers, the regulators required the banking company to comply with a long list of improvements of its controls and to submit to an independent review of its board, board committees, directors, management structure, and senior officers.

Does compliance keep Mr. Schaefer up at night, particularly in the post-Sarbanes-Oxley world? The issue is "huge," he acknowledged. "You have to be sensitive to the regulatory climate out there. When the examiners are coming in, they don't say 'Are you making money?' "

Fifth Third gave risk management a major overhaul. A week before the written agreement was disclosed, it created the position of chief risk manager and hired Malcolm D. Griggs to fill it. Mr. Griggs, a lawyer, was previously the risk policy director at Wachovia Corp.

In an interview, Mr. Griggs conceded that Fifth Third ran into problems because it had grown too fast. "If you hit a certain threshold, the $70 billion to $75 billion in assets, you got different standards and expectations" from regulators.

He created a risk strategy group, which is working on internal capital allocation models and looking into complying with the Basel II capital rules, which are not mandatory for a company of its size but may well be to its benefit, he said.

Mr. Griggs also created an affiliate risk management structure, with a senior risk officer in each of Fifth Third's 17 subsidiary banks and each of its four business divisions. Those officers report to both Mr. Griggs and the head of their respective bank or division.

According to analysts, these moves strengthened the company and rehabilitated its management team's reputation. "They were sloppy; there was a lack of attention," said Frank Barkocy of Keefe Managers LLC, a New York fund group. "It was a great learning opportunity, and they got their house in order."

The memorandum was lifted in April, and Fifth Third did not wait long before resuming its acquisitive ways; it closed the Franklin deal in June and announced one in Florida soon after. But Mr. Schaefer seems to prefer steering attention anywhere but to M&A and says the company doesn't view that as a core competency. He insists that growth is possible without another deal.

To achieve internal growth, he wants a bigger contribution from fee-generating businesses like payments processing, corporate treasury services, and asset management, all businesses that Fifth Third says will be major sources of growth.

Fee revenue will play a key role in the retail strategy, Mr. Schaefer said. "We know, when we do 100 mortgages we get 92 checking accounts out of those 100 mortgages, and we know we get 54 home equity loans, and we know we get 40 credit cards and 11 brokerage accounts. We are pretty good at that."

An ex-Army officer and a nuclear physicist by training, he is happy to let it be known that he drives his staff hard. "I stack-rank them. I know who is the best and who is the worst. And that forces the performance up." Those performing at the bottom of the scale selling products are "invited" to talk to those at the top to discuss measures to improve.

If their performance continues to lag? "You cannot maintain residence in intensive care," he said.

The loan book nearly tripled during the five-year period that ended December 2003, to $52.3 billion, though Mr. Schaefer said he is not after more assets in general. Fifth Third wants to cross-sell everything from foreign exchange services to transaction processing, he said.

During that five-year period profits from payment and transaction processing more than quadrupled, while net interest income just about tripled. Over the past 10 years processing income has grown more than tenfold, and net interest income has risen 566%.

Fifth Third has been in the processing business since the mid-1970s, so it has a substantial fee revenue base, and Neal E. Arnold, the former chief financial officer who is now the head of the payments business, said its clients have driven it to become more efficient.

The pressure of processing grocery payments "helped us to be ahead of the curve" in developing the technology that is now a major asset, he said. And Fifth Third wants to focus more on low-risk, high-volume transactions. "I care about volume, because I have more pricing power when I am a wholesaler."

Fifth Third is also one of many institutions building branches at a significant clip: Since January 2002 it has built 116, and it opened its 1,000th branch last month. A recent deal for First National Bankshares of Florida Inc. would add another 16 to its network.

Earlier this month, the company received regulatory approval to open branches in Pennsylvania, and a spokeswoman said Fith Third is planning to open two in Pittsburgh by yearend.

That deal, in which Fifth Third would pay a 41% premium, had some on Wall Street wondering if Mr. Schaefer is uncharacteristically overpaying. He said last week that the Florida market, which Fifth Third entered 15 years ago, is simply growing faster than the rest of the country and that its attractiveness justifies the premium.

First National is also the largest remaining independent bank in Florida, and buying it would make more sense that acquiring a string of small community banking companies, he said.

Fifth Third intends to use its own Florida branches and First National's as a springboard for expansion, mostly through building branches on the state's west coast. Mr. Schaefer said he plans to hire 50 commercial loan officers to lure small and midsize business borrowers. In the interview at his offices, he said, "When we open a branch there, it grows like crazy."

Not all analysts and investors accept that logic.

Denis Laplante, an analyst at Keefe, Bruyette & Woods Inc., said during a recent American Banker roundtable discussion that the growth opportunity in Florida does not justify the price Fifth Third is paying for First National. (However, he still named Fifth Third's stock as one of his top picks.)

The prospect of more costly deals may be weighing on Fifth Third's shares, which have fallen approximately 17% this year. Fifth Third was rumored to have talked to Charter One Financial Inc. of Cleveland this year before it sold to Royal Bank of Scotland Group PLC's Citizens Financial Group Inc. Also, Fifth Third was a finalist in the bidding for National Commerce Financial Corp. of Memphis, only to lose out to SunTrust Banks Inc.

And it was perhaps a shock when Fifth Third opened a branch in Chicago's Sears Tower. Mr. Schaefer acknowledged that the location "is unbelievably expensive," but he argues that even that investment is cost-efficient. About 30,000 people go in and out of the Sears Tower every day, he said. In contrast, "Ashland, Kentucky, has only 20,000 people, but we have four branches there."

Still, it is difficult not to sense the attention to cost in First Third's headquarters. Even now there are no company cars and no corporate jet. Mr. Schaefer drives his own Lexus to visit clients, and until last week he got reimbursed 27.5 cents a mile for gas, 10 cents less than the Internal Revenue Service allows a company to credit an employee. (On Wednesday the company told its staff via e-mail that it had raised the gas credit to 37.5 cents.)

Fifth Third's philosophy on costs has created a level of back-office efficiency that it says is unmatched, even by vendors seeking to get business from it.

And costs will always be part of the equation when Mr. Schaefer talks about Fifth Third's goals. He told investors at a conference last week in New York that cutting costs alone is not "a path to long-term success," but Fifth Third mentioned in its midquarter earnings update this month that it planned to cut $100 million of costs in the third quarter.