The inventors of Grain had the idea, the research and the coding in place for an app to help bank customers build credit, but they lacked a viable way to test their product.

Enter the fintech sandbox.

Regulatory sandboxes, which provide a framework for startups to vet products with consumers before pursuing a license or jumping through onerous hoops, have caught on more slowly in the United States than in other countries like the United Kingdom, which pioneered the concept.

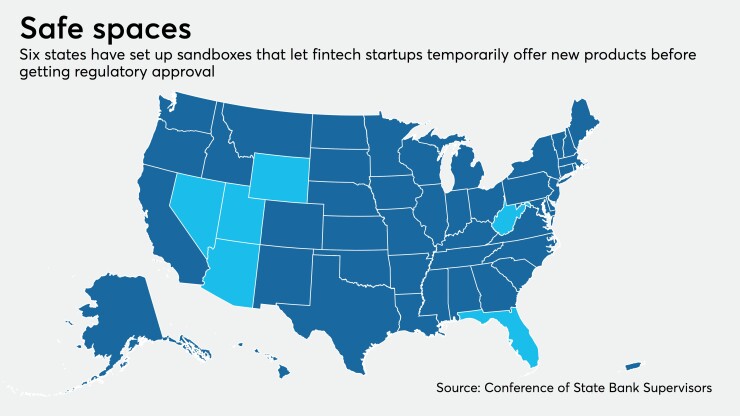

Florida and West Virginia passed legislation in recent months, joining Arizona, Nevada, Utah and Wyoming as states with fintech sandboxes. Several other states, including Illinois and North Carolina, have bills in the works.

Arizona, which in 2018 became the first state to offer a fintech sandbox, is the only one with active participants. But some early signs of success show that fintechs can emerge from this process with a promising product — and in Grain’s case, a bank partnership. The pandemic may increase consumers’ appetite for more innovative ideas.

Grain has found that the burden of medical debt is a big motivation for people trying to rebuild damaged credit.

“The market is changing and people are asking for different things in terms of financial services,” said Carl Memnon, Grain's chief operating officer. “The pandemic has exacerbated the need for mobile solutions.”

States are innovating beyond the sandbox concept.

The Multistate Money Services Businesses Licensing Agreement, or MMLA, which streamlines the money transmitter licensing process among 27 states, and regulatory sandboxes, “are not one-offs,” Catherine Pickels, communications director at the Conference of State Bank Supervisors, said in an email. “Experimentation is baked into this dynamic system of state regulation where states work together to harmonize and each state retains the ability to fulfill consumer protection and economic development mandates.”

How to play

Each state has its own rules concerning the eligibility, residency and reporting requirements for sandbox participants, but the broad goals are similar: to entice companies offering innovative financial products or services — including those in the areas of peer-to-peer lending, money transmission and cryptocurrency — to bring their business to the state.

“This is supposed to be a much lighter touch regulatory regime so you can trial and pilot concepts,” said Andrew Lorentz, a lawyer at Davis Wright Tremaine. “There is a balance between protecting consumers and enabling innovation with time and cost taken up by licensing.”

In all the states with sandboxes, firms won’t need a license to conduct limited tests on consumers for up to two years, though they may be subject to criminal and state consumer protection laws. Applicants must outline their plan for consumer protection and, once accepted, report to the overseeing agency and keep meticulous records.

“Companies have to open up their books so we can run checks to test their progress and make sure they are consistent with Arizona law,” said Arizona Attorney General Mark Brnovich, whose office oversees the state’s fintech sandbox. “We’re trying to reduce those regulatory barriers and eliminate companies going through various agencies to get approval to test a product that may or may not be successful. But it’s a sandbox, not a beach, so it’s not a complete free-for-all.”

Grain is based in the Bay Area, but Arizona’s rules allow nonresidents to participate, though they are subject to the state’s jurisdiction.

The startup was admitted in October 2018 and spread the word about its product — an app that connects a revolving line of credit, based on the income and spending, to an individual's checking account so they can use their debit card as if it’s a credit card — among friends of friends in Arizona, collecting up to 30 beta testers in the state. In 2019, Grain signed a deal with the $1.2 billion-asset Ponce Bank in New York City to provide the line of credit.

In West Virginia, a bill to set up a fintech sandbox was introduced last year but drew opposition from consumer advocates and other groups; a 2020 rewrite incorporated more consumer protections and input from other affected constituencies.

A major motivation for the bill was a desire to “invite new business to the state,” said Kathy Lawson, general counsel for the West Virginia Division of Financial Institutions, which oversees the sandbox. “It also gives us an opportunity to look at our laws and see where there is more opportunity for modernization and efficiency.”

The legislative session ended shortly before the pandemic impacted West Virginia. Lawson and Tracy Hudson, deputy commissioner of the West Virginia Division of Financial Institutions, scrambled to get the program up and running under emergency rulemaking by June 5.

Will fintechs dig in?

It’s unclear how attractive these sandboxes will be for budding entrepreneurs.

“To get venture funding and the attention of strategic partners, you can’t confine yourself to a single state,” Lorentz said. “I still find that clients want to go in other directions.”

But he says sandboxes have advantages when it comes to spurring innovation.

“It’s good for incumbents to see the lessons others are drawing, about how to reach customers and configure products, which they wouldn’t necessarily do without the pressure of competition,” Lorentz said. “And it gives insurgents the opportunity to prove their concepts and serve customers, particularly the underbanked, in ways they haven’t been served before.”

Hudson said the pandemic might lead to more activity in West Virginia’s sandbox.

“Licensing has picked up as companies are trying to extend their market a little bit," she said. "I think everyone is looking for a new way to reach different parts of the market, whether through licensable activity or an innovative product."

Lawson and Hudson have had about eight informal conversations with interested firms.

West Virginia is the first state to have sandbox entrants apply through the Nationwide Multistate Licensing System, or NMLS, meaning that once companies graduate, they can seamlessly apply for licenses in other states because a lot of the background work has already been completed.

As the only state sandbox with active participants, Arizona has welcomed 10 participants, including two that have exited. One of the graduates is Verdigris Holdings, a company that aims to serve the underbanked and unbanked and is

“One thing the pandemic has shown is how much technology matters in our lives and how innovation is changing the world,” Brnovich said.

Memnon said Grain wouldn’t exist if not for the sandbox.

“There are certain capital barriers to offer a product like ours,” he said. “When we discovered the sandbox we saw it as an opportunity to validate our idea in a controlled environment with the guidance and oversight of a regulatory authority.”

Grain is close to leaving the sandbox, but its reach has already extended well beyond Arizona. In December, the product was open to New York and California customers in Apple’s App Store. Grain became available nationwide in June.