From the beginning, blockchain technology has held out the promise of making intermediaries unnecessary. Never has this promise looked so good to banks as when it takes the form of smart contracts, which have the potential to slash back-office costs, create business opportunities and reduce the need for expensive lawyers and compliance officers.

But reduce doesn't mean eliminate. At the very least, coders will need to consult with lawyers to figure out the proper way to put the terms of an agreement into code. Banks' interest in smart contracts could even lead them to beef up their legal departments in the near term, as the financial industry and regulators alike continue to wrestle with the implications of blockchain technology.

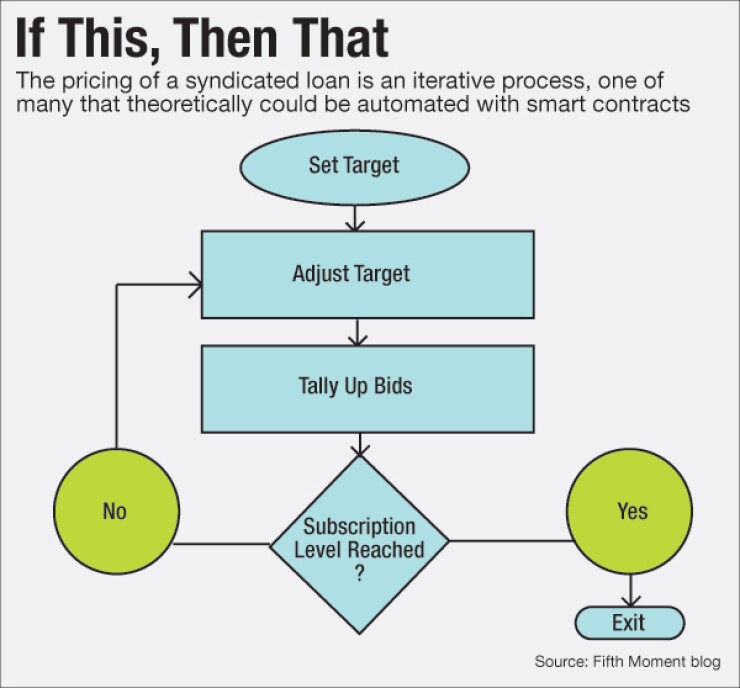

Fundamentally, a smart contract is a piece of software that executes its terms automatically and encodes rules agreed upon by all parties. Smart contracts are decentralized — living on a blockchain — and transparent, viewable by all parties. They can be used to transfer value, and that transfer is triggered in response to certain events.

-

A new blockchain protocol that has been in development for the past 18 months is ready for its public release.

May 2 -

The state of Delaware is looking to avoid prescriptive regulations when it comes to supervising blockhain companies, but instead be mindful of how the industry actually works, Gov. Jack Markell said Monday.

May 2 -

Delaware, whose business-friendly laws have lured more than half the country's publicly traded corporations and more than 60% of the Fortune 500 to incorporate in the state, is now vying to become a hub for blockchain technology.

April 5 -

The ability to program value exchanges without risk of censorship, moderation or theft gives smart contracts a leg up in servicing users who lack a mainstream banking association.

March 30 -

In focusing on private blockchains, banks make the same mistake companies made in the nineties when they favored private information networks over the open protocols of the Internet.

March 9 -

A concept that predated bitcoin itself is becoming more than a thought exercise as blockchains explore ways to harness smart contracts for greater uses.

January 8

Two of their chief benefits are automation and lack of ambiguity. Another is decentralization — the fact that everyone on the network can verify the validity of the contract, which eliminates the possibility of one unscrupulous professional undermining the whole system.

"It provides a very different trust model," said Ari Juels, a professor at the Jacobs Institute at Cornell Tech who serves as co-director of the Initiative for Cryptocurrencies and Contracts, a group of academic researchers. "If you believe that an agreement has been properly expressed in English prose and will be honored, then you may not need to rely on code to enforce the same agreement. But trust — in prose and other people — is very fragile, as we know. Code at least eliminates the fuzzy semantics of an agreement and the fuzzy trust assumptions that revolve around its execution."

For instance, a written contract might say that "prompt payment" will be made upon a piece of work being submitted and found acceptable by a client. But what determines the work's acceptability? What time frame does "prompt" indicate? With a smart contract, said Juels, "you can specify exactly when payment will be made and under what conditions."

Nilesh Vaidya, a senior vice president at the consulting firm Capgemini who is advising national and regional banks on blockchain applications, gives the example of a smart contract designed for microlending. It could "handle the entire loan process, from the time somebody sends in an application to the assessment of credit risk to the approval to its being issued by somebody to its servicing by someone else," he said. "We're talking about loan approval in minutes while the applicant is still at the location where the loan is desired."

If a single institution is handling it all, a smart contract doesn't provide as much benefit. But in developing countries, where it is more difficult to assess credit risk and where the entities equipped to manage one part of the process may not be able or willing to do the rest, a standardized smart contract could make it easier for them to work together.

"It can be done without smart contracts, but it helps to have that standard definition," Vaidya said. And the loans could be processed without the need to hire loan officers. Getting a loan would be more like buying a soda from a

At least one of Capgemini's clients is working on a proof of concept for just this kind of program, said Vaidya. Other financial institutions, startups and university researchers — including people at IC3, Juels's initiative — are conducting experiments. No such contracts exist in the wild, though that might soon change if a smart-contract investment vehicle known as

Privacy is a big challenge, given that the original bitcoin blockchain was designed for complete transparency. "If you can't solve the confidentiality of transactions, then people aren't going to use [smart contracts] for most use cases," said Tim Swanson, the director of market research at R3CEV, a startup that has put together a global consortium of banks with an eye toward applying blockchain technology to the world of finance.

What if smart contracts were to catch on? Ideally, the code would be reusable in the form of templates, cutting down on legal busywork. Just not all legal work.

"Lawyers will always have a strategic role, especially if people realize they can start doing more complex things operationally with smart contracts," said Danny Bradbury, the lead author of a report on smart contracts published by CoinDesk, a media organization. "They're going to need people to walk them through that stuff. What they might not do is pay the lawyer $600 an hour for six hours to go write the contract. "

That sounds pretty good to some legal professionals. "As a lawyer, one does not wake up and think, 'Wow, I can't wait to get into the weeds of some obscure clause in an 80-page prospectus,'" said Patrick Murck, a lawyer and researcher at Harvard University's Berkman Center. "You want to spend your time doing higher-level, creative work. And to the extent that technology creates a lever that allows you to do that, the better it is for you as a professional. So I don't see this as a threat to the legal community; I see it as an opportunity."

Smarts contracts don't yet have a legal framework to govern their use, and while their adoption could reduce lawyers' numbers over time, it seems likely that for now they will be kept busy trying to figure the technology out, said Brad Bailey, a research director at Celent.

Another unresolved question is whether the dominant system for smart contracts should be one or more private distributed ledgers, a new public blockchain such as Ethereum, or a so-called "sidechain" working in tandem with the established bitcoin network. "There are truly interesting battles taking place," Bailey said.

No matter which system ultimately wins out, Murck said, one thing seems certain: "The future is bright for lawyers who can code."