The power wielded by a small number of companies in the core processing market is one of the — if not the most — pressing issues that affects minority depository institutions wishing to innovate.

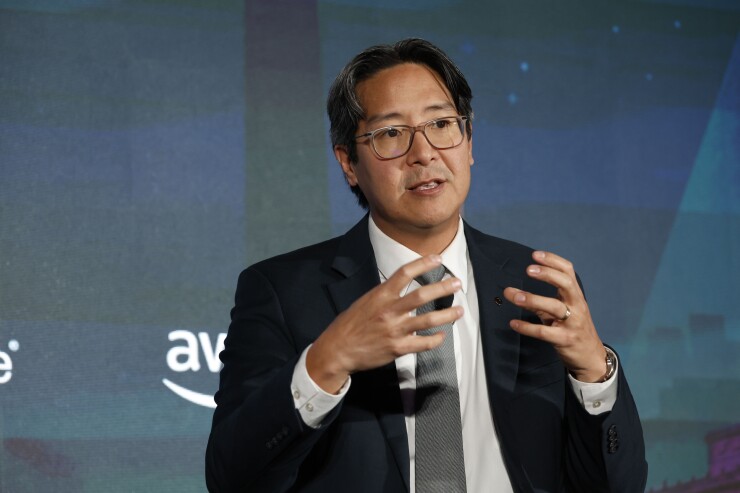

"In every single discussion I've had about banks, digital, and modernization, especially with community banks, all roads lead through the core," said Michael Hsu, Acting Comptroller of the Currency, said in a recent fireside chat hosted by the Alliance for Innovative Regulation. "I've heard a lot of frustration from community banks because they feel like hostages in these relationships and have no negotiating leverage."

That was one theme to emerge in a daylong set of panels and conversations on Thursday organized by AIR around its multi-year MDI ConnectTech initiative,

At stake is the ability for financial institutions focused squarely on under-resourced communities to be competitive and serve their audiences effectively.

Minority depository institutions have limited budgets and staff to upgrade their technology. Some are turning to secondment programs and like-minded fintechs to tackle these problems.

In her ongoing research as the program director for MDI ConnectTech, Alexandria Currie, of the National Bankers Association, found that cost is the number one barrier to minority depository institutions across the board in adopting technology. The institutions she examined ranged in size from $30 million of assets to more than a billion.

Staffing is next on the list.

"If I have the money, do I have the staff capacity to implement and learn the technology with my three to four-person loan department?" she said during a panel on MDIs and digital transformation. She pointed out that a

The topic of negotiating contracts with core services providers came up frequently as something complex and cost-prohibitive.

The three major core providers, FIS, Fiserv and Jack Henry, have grown through mergers and acquisitions, meaning different banks will have different experiences depending on which service they are using under the larger umbrella, said Rob Nichols, CEO of the American Bankers Association.

Currie has seen situations where, for example, a bank will sign a long-term contract with a core company only to find the provider is sunsetting that specific product midway through the contract and ceasing compliance updates. Yet the bank will have to pay to convert to a new system under the same provider.

"There are sticking points in contracts, and there is space in the regulatory environment to tighten that up and not allow some of these things to happen," she said.

Brian Argrett, CEO of CityFirst Bank, a $1.4 billion-asset institution in Washington, DC, echoed the thought.

"My question is, how can the regulatory community provide both pressure and perhaps policy that benefits small institutions?" said Argrett. "The imbalance in power makes it very difficult to change cores from a financial and contractual standpoint."

The cost issues facing MDIs can partially be offset through "being creative with other forms of finance that are loosely structured to let you use it for operational transformation," Argrett said, pointing to the

The broader issue of digitizing an institution with few resources can be tackled by taking small steps.

"Community bankers will say, we know we have to modernize but we don't know where to start," said Hsu.

He recalls one fintech investor recommending that banks start by digitizing their forms because it's a manageable project, pulls in different teams, and encourages the snowball effect once the institution sees an immediate impact.

He also suggests small banks boil down their strategy to a simple question: who is your future customer?

"MDIs and CDFIs are excellent with their existing customer base. They know them better than anyone," said Hsu. "But who is the future customer? Probably someone younger and more addicted to their phones."

Currie has advice for small banks to counterbalance some of the power the three major core providers wield: stop signing all-in-one bundled deals, which typically combine core data processing, card processing and online and mobile banking. Out of the 15 MDIs she assessed as part of her research, all had bundled their core contracts.

"That means even if I want to switch one of those things I'm now bound to all three for the term of this five, seven, or 10 year contract," she said.

Even though discounted pricing for all-in-one packages can be enticing, she finds it pays to shop around for digital banking and card processing services.

"I hear that everyone wants to go to a different core," she said. "That is not the solution. It's how we navigate within the confines we have now."

Current and former regulators also acknowledged the role they could play in guiding MDIs toward digitization.

Jo Ann Barefoot, founder and CEO of AIR, noted on one panel that one element she didn't appreciate as a former bank regulator is "the degree to which the examiners raise an eyebrow at some new piece of technology and the bank determines, I better not do that," she said. "We're going to have to reverse that. I'm dreaming of the day when a field examiner will come into a financial institution, see an antiquated piece of technology, raise their eyebrows and say 'I can't believe you're still on that.'"

The role of the regulator is especially potent when it comes to leveling out the balance of near-monopolistic power between the three major core providers and small banks.

"I wish I'd been more proactive in taking this on as an issue," said Hood of his time at the NCUA. "It's lamentable that in the wake of George Floyd, you had Wall Street investing in these institutions that serve communities of color but you didn't hear anything about the core providers."