The recent sell-off in bank stocks has had a predictable effect on merger activity.

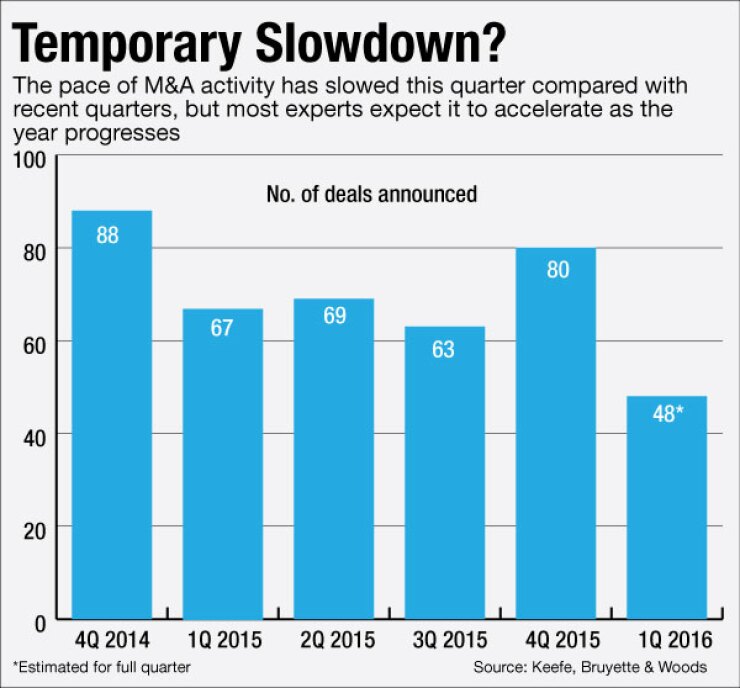

After a wild fourth quarter, when nearly 80 acquisitions were announced, the pace of deal making slowed considerably in January and February as stock values plunged and weakened acquirers' buying power. Only 32 deals had been announced through Feb. 29, compared with nearly 50 in the first two months of 2015, according to data from Keefe, Bruyette & Woods.

But many experts say the slowdown is just temporary and predict that M&A activity will rebound even if stock prices do not fully recover.

-

Mergers of equals are hard to complete due to cultural issues, but a spike in consolidation paired with weary leaders and a lack of young talent could make such combinations more appealing.

March 2 -

Texas has had a fair share of M&A since the financial crisis, but deal volume has declined since oil prices began to plummet in late 2014. Uncertainty over sellers' exposure and depressed stock prices for aspiring buyers are largely to blame.

February 26 -

There is a widening gap between the premiums paid for bigger institutions and those of smaller community banks. Economies of scale, scarcity value and earnings potential are more important than ever, and a return of larger acquirers has increased demand for bigger sellers.

February 18

With the Federal Reserve now signaling that it may not raise interest rates again anytime soon, many smaller banks will look to sell themselves rather than face another prolonged stretch of margin pressure, said Scott Siefers, an analyst at Sandler O'Neill. Larger banks, meanwhile, are likely to see acquisitions as the only way to meaningfully increase loan balances and profits.

"For the last half decade or so, banks have had this hope that the Fed would raise rates in each of the following years and finally provide some relief on margins," said Siefers, who recently lowered his 2016 earnings estimates on more than 100 community and regional banks. Though the Fed raised rates from near zero to a range of 0.25% and 0.5% in December, "it doesn't look like it will do anything more this year and maybe not next year, and that's going to lead to much more serious M&A conversations."

It is not just margin pressure that will drive consolidation. Mounting regulatory costs (potentially made worse by a

While stock market volatility is suppressing dealmaking for now, Chris Marinac, managing principal and head of research at FIG Partners in Atlanta, said he expects activity to pick up in the coming months as more bankers accept that the challenges they have been facing over the past few years are not going away. Spreads are still narrow, and there are still too many banks chasing too few quality loans, he said.

"Reality is going to set in. Banking's a tough business and it's going to be a tough year for bank stocks, but that doesn't mean M&A is going to dry up," he said.

What Marinac sees happening is sellers teaming up with preferred buyers and perhaps accepting a lower price now in hopes that shareholders can benefit from the buyer's stock appreciation down the road. It is also not a bad thing, he added, if buyers overpay a bit for lackluster performers.

"Sometimes you have to pay a premium for a mediocre company to create a truly great company," he said.

Though bank stock prices have rallied a bit in recent weeks, most still remain well below their trading prices at the end of 2015. The KBW Bank Index, which is made up of the country's 21 largest bank holding companies, stood at 64.02 midday Tuesday, up 13% from its mid-February low but still down 13% from late December levels. The decline might prompt active acquirers like BB&T, for example, to use a mix of cash and stock, rather than all stock, to get a deal done.

Low stock prices do not "change the long-term strategic importance of consolidation and scale for the banking industry, and I would expect we'll be as active in M&A in the future as we have been in the past," BB&T Chairman Chief Executive Kelly King told American Banker in February.

Shareholder activism also drove much of the activity in late 2015 and Dennis Trunfio, the U.S. banking and capital markets leader at PwC, said he expects that trend to continue this year.

While activists tend to set their sights on smaller banks, there have been more examples lately of larger firms being pressured to sell. Case in point: The $15 billion-asset Astoria Financial in Lake Success, N.Y., opted to sell to New York Community Bancorp not long after investor Basswood Capital Management began pressuring it to

"The fundamental reasons shareholders (and activist investors) believe consolidation in the banking sector is necessary have been widely discussed for years," Trunfio wrote in an email. "What has changed in the current climate is that shareholders appear to be taking action to try and overcome perceived inertia…and the difficulties management teams have in being able to articulate how they will get back to earning their cost of capital."

Poor succession planning, particularly at smaller banks, is also likely to spur more consolidation.

Robert Kafafian, CEO of the Kafafian Group in Bethlehem, Pa., said that the directors at banks he advises recently had a "deer-in-the-headlights moment" when they learned that the current CEO was not grooming a successor. That is common at small banks, he said, which often do not have the bench strength to promote from within and where CEOs are often reluctant to initiate searches for their eventual successors.

"Quite candidly, I would tell you that a lot of banks that want to remain independent will have trouble [doing so] because they've done a poor job of succession planning," Kafafian said. "It's going to startle a lot of boards into going out and finding partners."

Josh Siegel, the CEO at StoneCastle Partners in New York, agreed, adding that even community bank CEOs who are eager to groom successors often cannot do so because the talent pool is thinning. He said many colleges and universities do not offer commercial banking courses and that graduate schools of banking simply are not turning out enough future leaders.

"There are a lot of people being trained to be tellers or for credit jobs, but not enough being trained as CEOs or [chief financial officers]," Siegel said. "So what we have is a lot of experience at the lower levels and not a lot [in the C-suites] and it's going to continue to get worse."

Banks' lack of succession planning — as well as the desire for more scale -- could accelerate a recent trend in which buyers are acquiring banks closer in size to themselves, Siegel said. He pointed out that in 2004 acquiring banks were, on average, 8.08 times larger than the banks they bought. By 2015, the average buyer was 5.53 times the seller's size and in the deals announced so far this year, the average buyer has been less than four times larger. The $71 billion-asset Huntington Bancshares, for example, is about 2.8 times larger than the $25 billion-asset First Merit, and the $9.2 billion-asset Chemical Financial is just 1.4 times larger than the $6.5 billion-asset Talmer Bancorp. Both deals were announced in late January.

"Many buyers, particularly larger ones, don't see the benefit of buying these small banks," Siegel said. "They want to buy banks more comparable size to themselves."

— Paul Davis contributed to this article.