WASHINGTON — The White House and the Republican majorities in Congress have big plans for rolling back the Dodd-Frank Act and other aspects of post-crisis financial reform, but there are growing doubts that they will be able to deliver on the sweeping changes that they've promised.

Battles over health care, tax reform and other priorities are liable to eat up both time and political capital, while President Trump's team may have overpromised on economic growth, which could further sap policymakers' ability to enact reform.

Although the Treasury Department is expected to deliver a blueprint on regulatory relief by the beginning of summer, and House Financial Services Committee Chairman Jeb Hensarling, R-Texas, is working on a revised version of Financial Choice Act, both efforts face significant obstacles. Even actions taken directly by Trump's regulatory appointees are likely to be long in coming.

Following is a detailed look at the challenges facing efforts at reform.

A crowded agenda

The top financial policy priorities for the Trump administration are eliminating the parts of Dodd-Frank that it believes enshrined some banks as "too big to fail," reforming Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and reining in the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, according to Mark Calabria, chief economist for Vice President Mike Pence.

Speaking at a panel discussion Wednesday at the National Association of Business Economists, Calabria said "one of the driving forces behind the election is a sense that regulators during the financial crisis were, quite simply, in the game of picking winners and losers.

“We had 500-some banks fail" during the crisis. "We let them fail," he said. "Their shareholders took losses, and in some places creditors took losses. I think it’s fair to say the larger institutions were treated a little differently.”

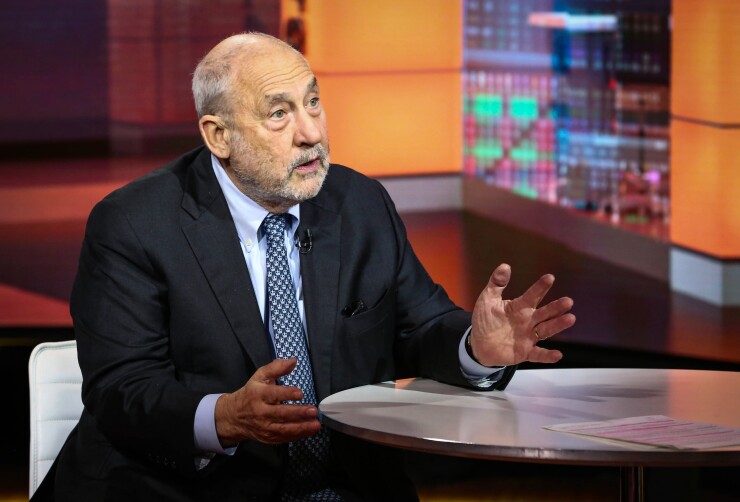

But Joseph Stiglitz, who chaired the White House Council of Economic Advisers in the Clinton administration, said that changes on that scale require legislation, and that without 60 votes in the Senate, Republicans' only way to make such alterations is through reconciliation, a seldom-used legislative process that allows a majority vote on items that directly affect government spending. That process takes time and limits what can be accomplished.

“This will be hard to stuff into reconciliation, and it especially gets harder because they’re not going to be able to put it in in 2017, so their only chance is 2018,” Stiglitz, who is now at Columbia University, said in an interview. “And my bet is they’re going to be strangling each other over Obamacare first, over the tax cut second, then over infrastructure.”

Brian Gardner, managing director of Keefe, Bruyette & Woods, said on the panel that items like eliminating regulators’ orderly liquidation authority, subjecting the CFPB to congressional appropriations and raising the threshold for a bank to be considered systemically important could potentially be included in reconciliation. But that may be it, he said.

“At the end of the day, frankly, some kind of reconciliation mechanism is the best that Republicans can hope for,” Gardner said. “Centrist Democrats talk a good game … about modifying Dodd-Frank. Six, maybe seven will vote that way, but there are never going to be eight that you need to get the 60 votes you need to make changes to Dodd-Frank.”

Economic expectations

The drive for regulatory relief may also be hampered by Trump's promises on growing the economy.

The president has made much out of the stock market’s recent rally since the election as a vindication of his policy preferences, tweeting March 2, “Since November 8th, Election Day, the Stock Market has posted $3.2 trillion in GAINS and consumer confidence is at a 15 year high. Jobs!”

Hensarling similarly emphasized economic growth during Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen’s testimony Feb. 15, saying the central bank should adopt a rules-based monetary policy because the Fed’s monetary policy behavior “severely compromises the kind of policy transparency and predictability that is necessary for household wealth to grow and American companies to create jobs.”

Senate Banking Committee Chairman Mike Crapo, R-Idaho, implored Yellen during her testimony on Feb. 14 to reconsider the Fed’s regulatory choices in order to kick-start economic growth.

“It will come as no surprise to you, Chair Yellen, that improving economic growth is a key priority for Congress this year,” Crapo said. “We all need to better understand the combined impact of these rules on lending, liquidity, cost for small financial institutions and broader economic growth.”

Yet while economic growth is clearly preferable to economic stagnation, many economists are uncertain the policies the White House appears to be pushing for will result in the kinds of growth figures that will justify those policies.

Douglas Elmendorf, dean and professor of public policy at Harvard Kennedy School of Government, said that “the rhetoric of this administration has clearly overpromised on economic growth,” even if it has not been long on details of what its expectations are.

The administration’s apparent yearning for the era of sustained GDP growth of over 3% ignores the underlying elements of productivity that were driving that growth — namely a wave of baby boomers entering or already in the workforce and rising numbers of working women, Elmendorf said in an interview. Today, the demographic realities are an aging population, retiring baby boomers and slippage of women’s workforce participation.

“Economic policy can change labor force participation in small ways, but there’s no policy being discussed that will push labor force participation back to what it was a few decades ago,” Elmendorf said. “If labor force growth is a percentage point below what it was before, then productivity growth will have to be a percentage point higher than it was before to get growth back to 3%. That might happen for some period of time … but certainly not in the middle of the distribution of possible outcomes will productivity growth suddenly be much higher than we’ve seen.”

Glenn Hubbard, who served as chair of the White House Council of Economic Advisers during the George W. Bush administration, said that while Trump has not explicitly promised anything in terms of economic growth, he certainly has reset the market’s expectations. That can be good, Hubbard said, because it unleashes the “animal instincts” of market and consumer confidence, which can buy the administration some time and flexibility to deliver regulatory and legislative changes that can boost productivity, which has been the main drag on growth for the last 15 years. But there is a danger of not delivering on those expectations, he said.

“I think there is a danger of overpromising … because those animal spirits will only take you so far, and then they become like Wile E. Coyote in the cartoon, where he’s running off the cliff and he doesn’t know it,” he said in an interview. “I wouldn’t use the word ‘probable,’ but I would use the word ‘possible.’”

Chris Thornberg, founding partner of Beacon Economics, said the fundamental problem with the White House’s growth plan is that it is based on the assumption that the economy is doing more poorly than it really is. While there may be some segments of the population that are not doing as well as they used to be several decades ago, even getting those workers back won’t result in large numbers of high-paying jobs. There simply isn’t enough room to improve on the current situation, he said, and other administration policies like cracking down on illegal immigration could counteract any improvements that do come along.

“On net, could you get a couple million more people to work? Yeah, maybe,” Thornberg said. “Those people are largely low-skilled, it’s going to take them a while to work their way into the workforce, they’re not going to be very high-income … in other words, those couple million people out there that you could refer to potentially as ‘slack’ really represent a small potential share of growth.”

Another complicating factor, Stiglitz said, is that if there is a financial crisis or some other unforeseen emergency, it can absorb all of the political willpower and momentum that might otherwise be directed at reg reform.

“When you have a crisis, it’s all-absorbing,” Stiglitz said. “Energy is limited, bandwidth is limited."

But Randall Kroszner, a former member of the Fed’s Board of Governors and head of the central bank’s supervisory committee during the financial crisis, said that those moments can also present an opportunity to make the kinds of reforms that might otherwise seem too abstract or remote.

“If we look historically, sometimes … some tumult in the economy can provide a foundation for change,” Kroszner said. “It will depend on the specifics, sometimes when something doesn’t go well in the economy … can get more support for legislative action of action at one of the agencies. It really depends on the circumstances.”

Timing is everything

If the performance of the economy is the metric that Republicans are using to define success of their deregulatory agenda – and if most of the gains that are likely to be made will come via regulation rather than legislation – then another complicating factor is simple timing.

Stiglitz noted that even though the administration has an opportunity to install a number of new members to the Fed’s Board of Governors, Yellen is not slated to leave her post as chair until early 2018, and the administration won’t have a full complement of Trump-appointed bank regulators until sometime next year. But the administration may not want to start softening bank regulations in a midterm election year, he said.

Calabria acknowledged some disappointment that nominations to open positions at the Fed, Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., Office of Comptroller of the Currency and the market regulators had not yet been made, but said that the administration “will make every effort” to fill those vacancies “in short order.”

But even with personnel in place, each rule takes several months or even years to complete, and it could be a long time before banks start to feel the relief they’re looking for today.

“The challenge is the timing, both in terms of the execution and the impact,” Kroszner said. “With regulatory change, sometimes you can get a relatively quick impact, but often it’s a longer run thing. It will change the incentives for investment, it will change the incentives for innovation, but the investments and innovations don’t happen overnight.”

Gardner said that some changes are more subtle and can be made relatively quickly, but can have a major effect. For example, new leaders at the bank regulators can set a tone on their first day by encouraging bank supervisors to clearly state expectations and take a less punitive approach toward gray-area regulatory violations.

“One of the easy ways to change the bank regulatory environment is that the bank will get the benefit of the doubt," Gardner said.

Great expectations

Another question is whether banks — and their investors — have priced in their loftier hopes for regulatory reform or the more realistic expectations of what may come from this administration. Goldman Sachs noted in a recent research note that the legislative changes are “less likely” while simpler regulatory changes — such as adjusting capital and liquidity standards — could unlock substantial values at many of the largest banks.

The March issue of Wolters Kluwer Blue Chip Financial Forecasts said that investors surveyed already have diminished expectations of tax reform going through Congress this year, down from 80% around the election to barely a majority today. Respondents also said their expectations for GDP growth in 2017 are only around 2.2%, and only 2.5% for 2018 — far below the 3-4% growth the administration is hoping to achieve.

Gardner said that, in general, the larger banks are aware that the most sweeping changes to the post-crisis regulatory regime are relatively unlikely and have set their expectations accordingly. That awareness tends to diminish as banks get smaller, however, and the midsize and community banks may still have unrealistic expectations on what the administration can deliver.

But for publicly traded banks and the institutional investors who buy their stocks, he said, the expectations for reform are appropriately modest, notwithstanding the recent market rally.

“I’ve been waiting for expectations to reset, and to my surprise, I think they already have,” Gardner said. “I think there’s a sense of realism on the buy side, at least from the investors I talk to. I was worried about that a few weeks ago, but I’m not anymore.”