When Rabobank Group announced in August 2004 that it was planning to buy the government-sponsored Farm Credit Services of America, it signaled big U.S. plans for the Dutch giant. But when that deal fell through two months later due to political pressure, Rabobank scaled back its ambitions, focusing less on big deals here and more on organic growth and bite-sized acquisitions.

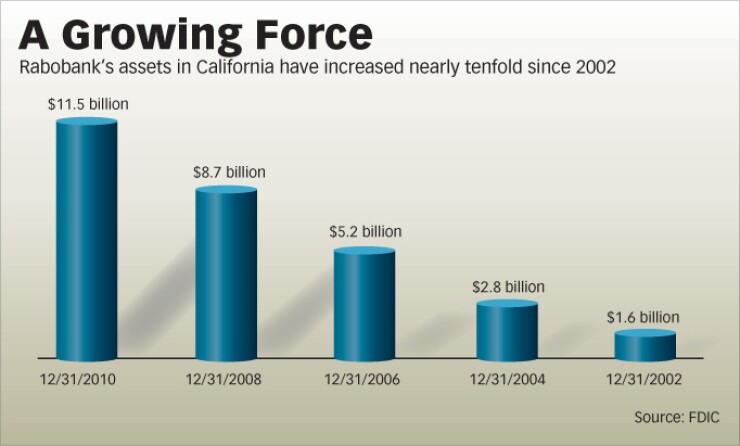

Now Rabobank, one of the world's largest agricultural lenders, is getting restless. Its U.S. banking unit, Rabobank N.A., bought three banks in California last year, boosting its assets to $11.5 billion and significantly increasing its share of the ag-loan market in the nation's largest farming state.

Meanwhile, its U.S. financing company, Rabo AgriFinance, is gearing up for a major expansion under chief executive John Ryan, with plans to double its footprint over the next four to five years, mainly through organic growth.

"We recently went through on a worldwide basis looking at ... what countries we want to be active in, and the United States came out on top as one country where we see tremendous opportunity," Ryan says.

Rabobank executives insist that the growth will be deliberate. Its California bank is taking a break from deals while it integrates the three banks it bought last year and, for now, has no plans to buy banks in other states, according to Ronald Blok, Rabobank N.A.'s chief executive. And Ryan says that while the financing unit would consider acquisitions, it's not planning to seek out deals.

Still, competitors will be watching Rabobank's moves with interest. Rabobank is already a major ag lender in parts of the U.S., and with its deep pockets, AAA-credit rating and cooperative ownership structure that allows it to offer better rates than many of its competitors, observers say it could soon emerge as an even more formidable foe.

"Just give 'em time," says Curt Covington, a former Rabobank employee who's now a senior risk manager at Bank of the West. "They are a pretty methodical, but very driven, organization. And they have a pretty compelling story to tell."

Rabobank is a direct descendent of two of the Netherlands' oldest banks, Raiffeisen-Bank and the Boerenleenbank. Both were founded in the late 19th century and in 1972 they combined, taking the first two letters of each to form Rabobank.

Throughout, Rabobank has specialized in agricultural lending, maintaining a cooperative ownership structure that eschews dividends and instead allows for plowing profits back into the business. The company has nearly $900 billion of assets and 58,000 employees in 48 countries.

In the U.S., Rabo International has operated out of New York with a handful of offices for three decades, offering sophisticated banking to large agribusinesses such as Cargill and Archer Daniels Midland. But the company had no retail banking presence here until 2002, when it acquired Valley Independent Bank in El Centro, Calif. At the time, its then-U.S. banking head, Cor Broekhuyse, said Rabobank's goal here was to replicate its "country banking" model that it has so successfully employed in such countries as the Netherlands, New Zealand and Australia.

A year later, it acquired an agricultural finance company in the Midwest that was the predecessor of Rabo AgriFinance.

The bank, led Blok, has offices only in California and is responsible for the agricultural lending business in that state. St. Louis-based Rabo AgriFinance, led by Ryan, does the rest of Rabo's U.S. ag lending from loan production offices outside of California. And a third executive, Ruurd Weulen Kranenberg, runs the big-customer wholesale business from New York. (Rabo designed those reporting lines-which leaves no one executive in charge of U.S. strategy-in a restructuring last year after Broekhuyse's retirement.)

Blok says that when Rabobank Group did its feasibility studies on where to expand in the U.S., it made the decision to start in California for two reasons: The sheer size of the state's agricultural sector-it produces $63 billion a year -and the efficiency of the community banking system.

"In California, it's very well-developed, and the way the community banks interact with their customers, with their employees, with the communities they operate in, is very similar to the Netherlands," says Blok, who came to California as CEO of the bank unit in 2006 after 14 years in the company's wholesale group, serving large customers in a series of stops from Chile to Singapore to Europe.

Rabobank built its California base largely through three deals between 2002 and 2007, and further expanded last year with three deals in the span of four months.

In April, Rabobank entered wine country when it purchased the one-office Napa Community Bank and in August it picked up two failed institutions in the same day: the $499 million-asset Butte Community Bank in Chico and the $312 million-asset Pacific State Bank in Stockton.

"We were very interested in all three of them because they were in areas we wanted to be," says Blok. "We had hardly any presence in these areas and from an ag lending side, they make perfect sense to us."

The three deals boosted the bank's total farm and farmland loans by 20 percent, to $2.4 billion. Among banks based in California, only the $1.1 trillion-asset Wells Fargo & Co. and the $58 billion-asset Bank of the West have more agricultural loans on their books, according to Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. data. (A Wells Fargo spokeswoman said the bank would have no comment on competitor Rabobank.)

The deals also added nearly two-dozen branches, giving it 123 throughout the state. Notably, though, it has no branches in Los Angeles County, the immediate San Francisco Bay Area, or San Diego because, Blok says, "We don't understand the big cities as well as the others do."

By concentrating on more familiar territory, he believes the bank can better execute its strategy with borrowers.

"We want to be the one-stop shop for everything to do with banking," he says. We want to do two sides of the balance sheet with them. And in these smaller to medium-sized towns, the farmers and ranchers are the key business people in these towns."

Many competitors say that while Rabobank has become increasingly visible in smaller communities, it isn't necessarily vying for the same business they are. Robert Hahn, CEO of Community Valley Bank El Centro, says Valley Independent Bank, which Rabo acquired, had been the "preeminent" bank for small businesses, for which agricultural lending was just a piece. Now Rabobank is focusing on much bigger deals than Valley Independent used to.

"They have pulled back; unless it's a $2 million deal or greater, they are out of the market," Hahn says. "I don't see them on the street against us or the local credit unions in those ranges."

Charles T. Chrietzberg, Jr., CEO of Monterey County Bank says that while Rabobank is "easily the No. 1 ag lender" in Monterey County, "they're a lot more interested in making a $25 million ag loan than a $250,000 business loan, which is good for us."

Still, says Hahn, "I respect them. They fill a need. A small community bank can't give anybody a cattle loan for $5 million, because we don't have the expertise. And they have people on the street here, where the major banks send folks down from San Diego or L.A. They have a community presence here that the majors don't."

Blok deflects suggestions that Rabo focuses on agriculture at the expense of other types of lending: "Providing financing to small and medium-sized businesses, as well as consumers and agriculture, is at the core of our mission as a community bank and we are committed to helping our local businesses grow and succeed."

While Blok oversees the expansion of the bank, it's Ryan's job to build up Rabo AgriFinance, which has $5 billion of assets. During a 10-year career as CEO of Farm Credit Canada, Ryan tripled the government lender's loan volume and his mission at Rabo AgriFinance seems to be to achieve similar growth.

Today, Rabo AgriFinance has two dozen offices, each with anywhere from three to 15 employees, stretching from Washington and Oregon in the west to Indiana, Tennessee and Arkansas in the east. There are another 15 locations where "relationship managers" work from home or satellite offices.

Ryan's plan, over the next two years, is to convert many of those locations to full-fledged field offices: 10 to 15 in 2011, and a similar amount in 2012, so that there are 40 field offices by the end of 2012. The number of "field managers" should triple to roughly 150, and Rabo AgriFinance has taken out new office space in St. Louis to accommodate headquarters growth.

Ryan, who joined Rabobank two years ago, says his division is looking for loans of $500,000 or more, and that it will generally do a smaller loan only if it's a foot in the door to more deals. The typical customers are producers "who are of significant size now, and are going to continue to grow." Smaller farmers have lots of banks to help them, he says.

Echoing the community bankers in California, those in other states say they have never viewed Rabo AgriFinance as much of a competitor, because it tends to target larger credits. And besides that, it has no visible branch network.

That could change, though, as it expands its footprint throughout the grain belt.

John Engelbert, president of First State Bank in Norton, Kan., says his bank has several customers with loans in the $1 million to $2 million range, "and if Rabobank came into this area, they would be the ones they'd try to cherry-pick. I'm sure we'd have a difficult time competing with them on interest rates."

Roy Becker, the ag finance specialist in the credit administration department of Dakota Bank in Aberdeen, S.D. says Rabo AgriFinance has approached some of his bank's customers for refinancings, offering better rates for longer terms.

Still, Englebert says his bank mainly considers its major competition to be the Farm Credit System.

"They're supposed to be the lender of last resort, but they're not afraid to cherry-pick your best customers, by any means. We're much more concerned with them."

Rabobank Group's strength, combined with the U.S. banking casualties of the credit crisis, seemed to have presented a perfect opportunity for it to start buying banks outside of California.

"They are one of those banks out there you see on the move, picking up some pretty key banks, and if they're targeting agricultural portfolios, then why not somewhere in the Midwest or other agricultural states?" asks David Heathcock, executive director of the California Independent Bankers group.

But Rabobank seems content to continue on the twin course of having retail branches in California while servicing the rest of the U.S. through its financing arm. "For the time being, California offers us a great opportunity to grow," Blok says. "We truly believe in what we call knowledge-based bankingunderstand what you do and try to do it as well as you can."

Growth via acquisition within the state may not occur in 2011, however. "We've done three acquisitions in a yearwe need to sit back a little bit and get them absorbed. Two of them were failed institutionswe need to get them back to work. It's a big job."

As for another attempt at a U.S. mega-deal, the strategic review described by Ryan "didn't automatically translate into 'Let's go and try to buy something,'" he says. "I'm not saying if there's a real big opportunity to do acquisitions we wouldn't go down that path, but we feel we've got a successful track record in terms of what we've done organically."

The aborted attempt at buying Farm Credit, says Bank of the West's Covington, had raised everyone's expectations for Rabobank, including its own. "Having said that, Rabobank's got the capital base, they've clearly got the reputation, and I think they've got, in a lot of areas, the expertise to take the next step."