-

Responding to lawmakers frustrated that the small business lending program has yet to dole out any funds, the Treasury Secretary said the fault lay with the banking regulators.

June 22 -

The Small Business Lending Fund will not provide the boost to economic activity hoped for when it was enacted. Banks have again had the rug pulled out from under them.

June 8 -

The Treasury Department is notifying Small Business Lending Fund applicants that they will not qualify for the program if regulators have restricted them from paying dividends.

June 1

Bankers are fond of the Small Business Lending Fund, but the SBLF is playing hard to get.

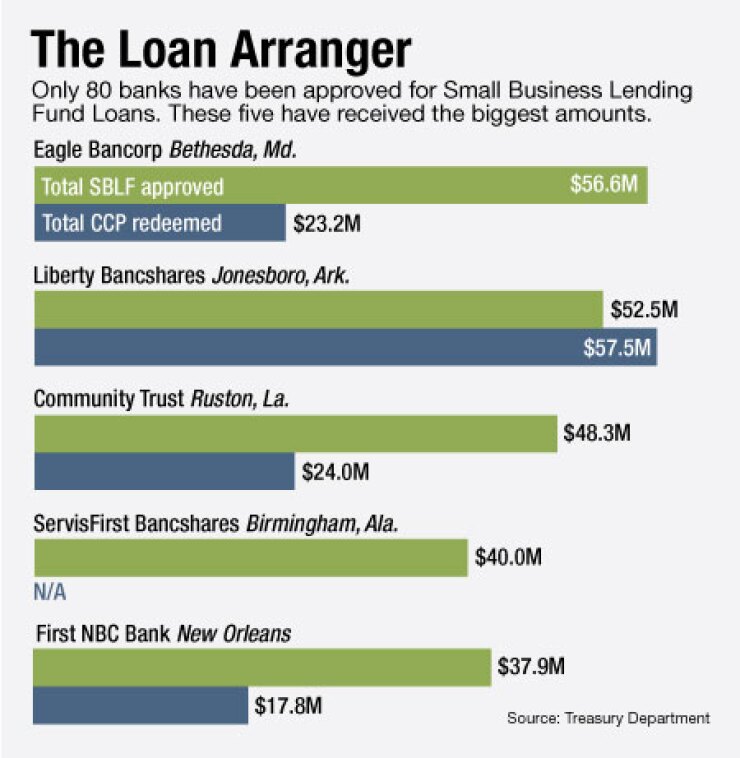

The Treasury Department has approved 80 banks for SBLF funds, but hundreds of others are waiting or have given up because of holdups tied to their age, size or dividend restrictions. Those not approved by the Sept. 27 deadline could face higher dividend costs and few capital options, as they seek other ways to fund their exits from the constricting Troubled Asset Relief Program.

Some Tarp "banks may consider a stock offering if they don't get SBLF and that window has closed because of volatility in the markets," said Kip Weissman, a partner at Luse, Gorman, Pomerenk & Schick. "Everyone is very concerned there will be banks that just run out of time."

Jason Tepperman, director of the Small Business Lending Fund, said the department is "very confident that we'll be able to come to decisions on all banks, and fund those that participate, by the end of September." The Treasury could not say how many applicants have been adversely affected by a dividend restriction.

Still, with just 3% of the SBLF's $30 billion invested so far, observers wonder whether the Treasury would even be able to fully vet all of the applications.

"I doubt you will see the $30 billion totally allocated," said Dan Yates, president and CEO of Regents Bank in San Diego. Regents withdrew its application after discovering "certain nuances" that would have given it less capital than what it received through Tarp.

In its third and latest round of approvals, 37 banks were accepted on Wednesday, compared to 20 on Aug. 3. More than 900 applied to the program.

"It looks like they are setting up for a mad dash to finish," Weissman said. "The Treasury is assuring us that they will be able to get the job done, but people are scared. They're very nervous."

Most bankers said the hold-up is not so much at the Treasury as it has to do with regulatory and economical snags before applications reach the agency.

One roadblock involves instances where a bank has a dividend restriction, typically due to an enforcement action. Such banks must get a waiver from their regulator to proceed. Few, if any, have received one, observers said. The Treasury Department said several applicants have worked with regulators to obtain a waiver.

"The concern is that the Fed is just not acting on these waivers," said Paul Merski, the chief economist at the Independent Community Bankers of America. "The real consequences are that you're just going to pull in the horns. The whole purpose of adding capital is to free up banks' ability to lend."

The ICBA sent a letter to the Federal Reserve Aug. 10, urging it to work closely and promptly with the Treasury to resolvie the dividend restriction. Merski said the only response was the Fed acknowledging they had the letter.

A Fed spokesman did not immediately respond, but said after deadline that they planned to reply to the ICBA's letter.

There are also states, such as Connecticut, that have statutes barring banks from paying dividends until they reach a certain level of profit. This is holding up younger, state-chartered banks that opened during the financial crisis, including Connecticut Bank & Trust Co. in Hartford.

The seven-year-old bank had received approval from the state commissioner to get $5 million in Tarp and applied to refinance through the SBLF. That came to a halt in May when the Treasury issued a rule requiring waivers for banks with dividend restrictions.

"I explained the situation to Treasury, and all we've gotten back is a receipt application," said Anson Hall, the bank's president and CEO. "That was in March."

"I wish the Treasury had taken a more wholesome look at" the restriction, said Howard Pitkin, Connecticut's banking commissioner. "I'm not sure … any other state can address it."

Some bankers said they haven't heard from the Treasury since applying, which could be due to a lack of resources at the Treasury, observers speculated.

"SBLF is more like an economy car," Weisman said. "It's well designed … but they probably skimped a little on resources. That's why they're a little behind at this point."

Others noted the program has ran more smoothly once the Treasury began to approve applicants in July.

"It was not a difficult process," said William Moss, president and CEO at Community Partners Bancorp. The Middletown, N.J., company received $12 million from SBLF on Aug. 11 and exited Tarp using $9 million of the fund. The SBLF "is an improvement over the CPP in that it's directly correlated to stimulating loan growth."

Yates agreed the SBLF runs smoother with less restrictions than Tarp, even though the bank withdrew its SBLF application. After applying, the bank discovered it could not refinance all of its Tarp funds into SBLF. The Treasury does not let a bank be in both programs.

"The banks that have taken funds will work diligently to achieve those [qualified loan] hurdles but it remains to be seen if they can accomplish that," he added. "For it to really have a true advantage for community banks, you must meet the benchmarks of new business production on C&I lending … and demand is very tepid in our area."

Bankers with Tarp funds like the SBLF since they can refinance at a lower rate, leading to lower dividends and better quarterly results. To get a lower rate, they must meet a certain threshold of "qualified" business loans. This is tough in markets where quality loans are hardly replacing the ones being paid off.

Due to anemic loan demand, many banks have shrunk, making it difficult to justify refinancing with SBLF after receiving TARP at a time when they were larger.

NewBridge Bancorp in Greensboro, N.C., withdrew its SBLF application, estimating that it would have a $10 million to $15 million capital shortfall in refinancing its Tarp. NewBridge received $52 million in Tarp but it qualified for less SBLF funds because it has shed so many assets. Paying off Tarp would require selling common stock as a supplement.

"The SBLF is a good program … but if you shrunk your balance sheet, you're going to have to address the same issue," said Pressley Ridgill, president and chief executive of NewBridge. "Until we see how many people actually take the money, it's hard to see" the overall benefit. "I don't view it as something that's going to change the environment."