The Small Business Administration has renewed a push to nearly triple the cap for loans in its popular SBA Express program.

Testifying before a House subcommittee, Associate Administrator William Manger said Tuesday that the current $350,000 lending limit is outdated and that SBA Express’ performance is suffering as a result. The agency wants the cap raised to $1 million.

The program "has not been performing as well lately and we think that’s because the cap is too low,” Manger said. “If you took into [account] inflation, we’d be well over $500,000 now in that program. It needs to grow with the times.”

The SBA initially proposed to increase the cap in its budget for the 2019 fiscal year, but the proposal was excluded from the budget deal President Trump signed earlier this month. The agency will make an identical request in its 2020 fiscal year budget, which is expected to be made public in March.

“We are asking, through the president’s budget again, to increase the cap on Express loans to $1 million," Manger said. "That is something we think would be very helpful."

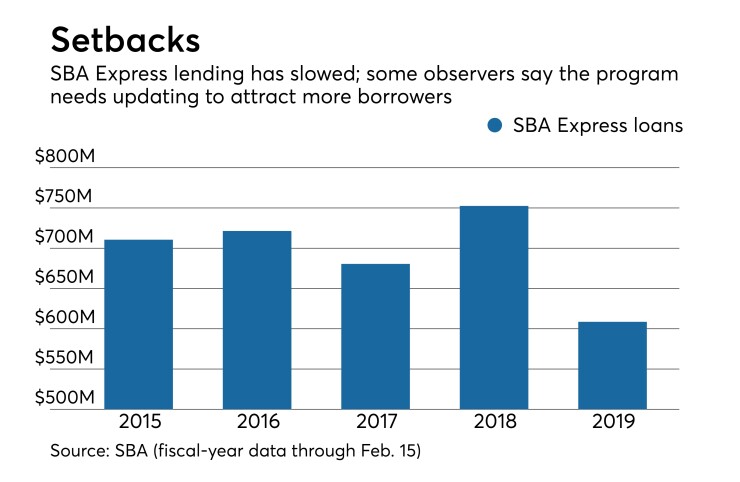

On Feb. 15 the amount of SBA Express loans backed by the agency in the 2019 fiscal year was down about 19% from a year earlier, at $608.6 million.

The downward trend persisted despite what Manger described as a tremendous rebound from the recent 35-day government shutdown. The agency has approved more than 7,900 loans totaling more than $3.7 billion since the shutdown ended, Manger said.

“We are now back to pre-lapse levels in all of our lending categories,” Manger said.

SBA Express is a component of the agency’s flagship 7(a) program, which offers loan guarantees as high as 85%. Under SBA Express, which was created as a pilot program in 1995 and made permanent in 2004, the agency put in place a streamlined application process allowing lenders to use their own forms and underwriting guidelines in exchange for a reduced, 50% guarantee. It promises a 36-hour turnaround time, where regular 7(a) applications can take up to 10 business days.

Under SBA Express, loans can be structured as seven-year lines of credit, which adds to their popularity with lenders, Manger said. Regular 7(a) loans can also be structured as credit lines, but there are significant limits on how funds can be used.

To date in the 2019 fiscal year, about 40% of all 7(a) loans have been submitted under the SBA Express program, making it one of the agency's most popular offerings. For all of the 2018 fiscal year, however, SBA Express accounted for 47% of the number of 7(a) loans.

The SBA's proposal would restore the provisions of the Small Business Jobs Act of 2010, which authorized a one-year increase in the SBA Express threshold, to $1 million. During the year the expanded limit was in place, the dollar volume of lending under SBA Express spiked to a record $2.8 billion.

Manger’s comments, given in response to a question by Rep. Tim Burchett, R-Tenn., seemed to catch lawmakers off guard. None commented on the proposal.

Bankers, too, appear wary to venture an opinion.

Jean Hale, chairman and CEO of the $4.2 billion-asset Community Trust Bancorp in Pikeville, Ky., said she couldn’t comment until she saw the proposal. A spokesman for TD Bank also declined to comment.

Tuesday’s hearing was organized by Rep. Judy Chu, a California Democrat who chairs the House Small Business Committee’s Subcommittee on Investigation, Oversight and Regulation, to look into what impact the government shutdown had on small businesses.

Chu described the shutdown as “35 days of missed paychecks, delayed loans and strained budgets for too many of our federal employees, contractors and small-business owners.”