HarborOne Bancorp in Brockton, Mass., turned to its backup plan to lock down its first bank acquisition.

The $2.7 billion-asset HarborOne is a mutual holding company, so it can merge with other mutuals. Money doesn't change hands in those deals, making them advantageous to growth-minded companies that are reluctant to shell out cash.

But social issues can make mutual mergers difficult to pull off. HarborOne spent months talking to "more than a handful" of targets, said Joseph Casey, the company’s president and chief operating officer. In the end, it was unable to find another mutual to absorb.

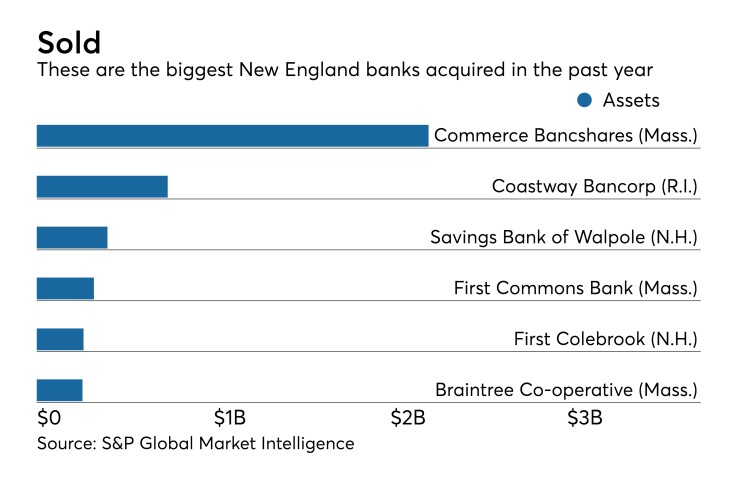

Management was fortunate that Coastway Bancorp, a state-chartered thrift in Warwick, R.I., became available. As part of its roughly

While HarborOne, which rolled up several credit unions before converting to a mutual in 2014, is keen on buying more banks, it could be limited by the lack of opportunities in New England.

And some industry observers believe the dilutive nature of the Coastway deal puts the company on a path to becoming a fully stock-owned company. That would be a tough choice for HarborOne's management, which remains interested in merging with other mutuals. (Companies are

“Our preference would be, as long as we have the structure, to merge with other mutual banks,” Casey said. “Those are economically superior than doing a dilutive transaction. Until we're successful in that regard, we would consider acquisitions of publicly traded institutions, but there are not a lot available.”

The decision to finalize a bank acquisition has taken a toll on HarborOne. Its shares are down 9% since the deal was announced on March 14.

It will likely take more than six years for the company to earn back the expected dilution to its tangible book value, which seemed to spook some of its investors, said Mark Fitzgibbon, an analyst at Sandler O'Neill. Many investors get nervous when the earn-back period extends beyond five years.

The all-cash deal will deplete HarborOne's excess capital, increasing the likelihood that it will eventually convert to a fully stock-owned company, Fitzgibbon said. "That time frame has moved up dramatically,” he said.

HarborOne's management has opted against a second-step conversion because it doesn't want to raise a significant amount of capital only to feel pressure to redeploy the funds, Casey said.

That being said, management and the board constantly monitor appropriate capital levels, Casey said.

“We want to be prepared for a downturn,” Casey added. "The board will consider where we're comfortable given our ongoing business plan and our thoughts on where the economy is going over the next several years."

HarborOne's trajectory could also be shaped by its ability — or inability — to merge with another mutual.

Such deals are hard to evaluate financially since no money changes hands, said Kip Weissman, a partner at Luse Gorman.

“When you have two bidders, in general it is pretty clear who is giving a better deal,” said Weissman, who declined to discuss HarborOne specifically. “In general, a mutual merger is way more amorphous. You have to look at other factors and it becomes trickier. Social issues are among those factors.”

Still, Coastway made a lot of sense, Fitzgibbon said. HarborOne already has a commercial loan office in Providence, R.I., with three lenders and a $400 million portfolio. The deal would also allow HarborOne to be less reliant on mortgage banking, which can be a volatile business.

Revenue tied to mortgage banking should fall from roughly 29% last year to a little more than 20% after the Coastway deal closes, Fitzgibbon said. HarborOne

“It is a deal they can comfortably execute on and it does make sense with their strategy of expanding into adjacent markets,” Fitzgibbon said. “Maybe most importantly it leverages their excess capital and puts them in a position where they can contemplate a second-step conversion.”

Despite the challenges, HarborOne executives are comfortable pursuing more bank acquisitions given their experience with other deals, Casey said. A big difference between buying a bank and merging with a credit union is negotiating the price, he said.

Credit union deals were "easy because they would come to us," Casey said. "There wasn’t a bidding process [or] an extensive commitment to get a 'yes' answer.”