-

It might take "another year from now" to finish Dodd-Frank rules that seek to end "too big to fail," Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke said. That was a slower timetable than that given by Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew.

July 18 -

Other countries are discussing implementing capital reforms that go beyond Basel III after the U.S. proposed a leverage ratio higher than the international accord, Federal Reserve Board Gov. Daniel Tarullo said Monday.

July 15 -

Federal Reserve Board Chairman Ben Bernanke said Wednesday that regulators are making steady progress on a number of critical rules under the Dodd-Frank Act, predicting that several final rules will be released in the coming months.

June 19 -

On eve of law's second anniversary, regulators face heavy scrutiny over how they will implement remaining Dodd-Frank rules. Many key regulations have yet to be seen.

July 13

WASHINGTON Getting different regulators to agree on joint rules has become the biggest obstacle to completing the Dodd-Frank Act, and three years after the law's passage agency officials are more inclined to admit the process is wearing on them.

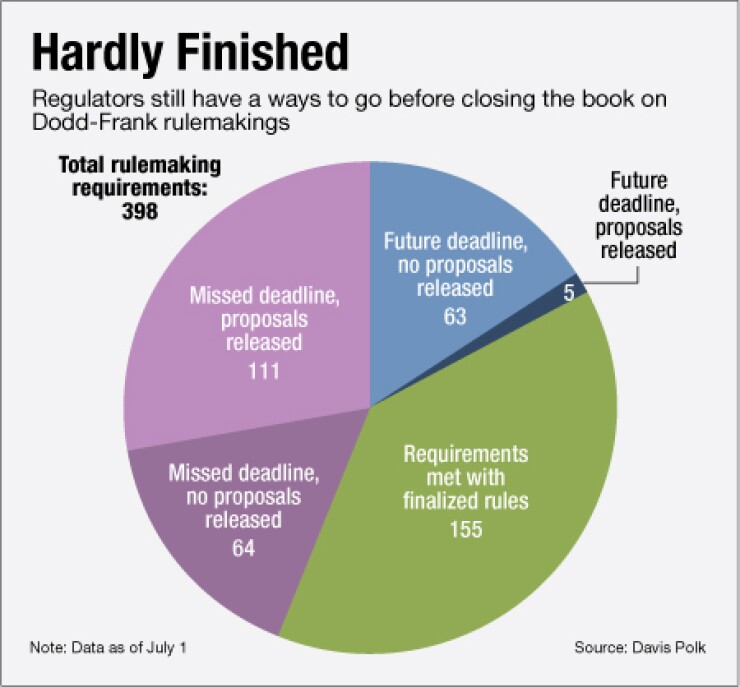

On the law's third anniversary, many key provisions requiring interagency rulemaking from banning proprietary trading to rules for securitized mortgages to derivatives restrictions are still unfinished. The joint rule-writing process has been fraught with agency disputes and the drudgery of brokering agreements, inevitably slowing progress.

"It's a painful process at times," Richard Cordray, director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, said at a recent Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. board meeting, discussing the difficulty of interagency consultation during his year-and-a-half tenure. "It's a frustrating process at times. It necessarily prolongs the work that is done. But it almost inevitably, if people work together, can make the work better, sounder, and stronger."

Federal Reserve Gov. Daniel Tarullo, the central bank's point person on drafting Dodd-Frank rules, recently called the process "very long and frustrating" given the time it has taken to finish rules representing the biggest overhaul since the Depression.

The items still unchecked on the to-do list are crucial areas of the statute. Topping the list are restrictions curbing banks' ability to do their own in-house trading, and a rule requiring lenders to retain some credit risk of loans they securitize. A key element of both rules is what activities will be exempted. For example, in the securitization rule regulators must establish a new status of safe loan called the "qualified residential mortgage" that allows lenders to skip risk retention.

In the trading ban known as the Volcker Rule since it was proposed by former Federal Reserve Board Chairman Paul Volcker the disagreement has stemmed from banking and market regulators, which must finish the rule together, having different philosophies. (In addition to the CFPB, Fed and FDIC, the joint deliberations have also involved the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission.)

Observers say regulators have clearly become more transparent about the cumbersome nature of being forced to work together.

"If they were cautious about talking about that before, it was probably just because it wasn't so incredibly painfully obvious two years or arguably a year ago," said Douglas Elliott, a fellow at the Brookings Institution and a former investment banker at JPMorgan Chase. "I suppose they might have worried if they were too realistic in their discussions earlier, they might have been seen as defeatists."

Marcus Stanley, a policy director with Americans for Financial Reform, said regulators' dissatisfaction with the process has included acknowledgment that some of the joint proposed rules they are trying to put into final form were subpar.

"Regulators are kind of coming out and saying more publicly this process has not been working in a lot of ways," Stanley said. "Not only have they had problems in finalizing rules, but there's also been an admission that the proposals are not really enough to do the job essentially."

Still, there are signs that the painstakingly slow process is nearing completion.

Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew predicted Wednesday that much of the remaining work left for regulators would be completed in the next five months. "Let me repeat: by the end of this year, the core elements of the Dodd-Frank Act will be substantially in place," Lew said, noting that progress going forward would be measured in "weeks and months, not in years."

Others are less optimistic. Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke, for example, told lawmakers on Thursday it could take another year to put in place all the rules meant to end "too big to fail."

In the last two months, regulators have made strides in the rule writing process, finishing up capital rules, proposing a new leverage ratio, taking early steps toward money market mutual fund reform, and designating two nonbank firms as systemically important financial institutions. But there's still more work to do.

Regulators have promised to finish the Volcker Rule by year end, along with simplified mortgage disclosure rules, capital and margin rules for derivatives and prudential standards for banks and nonbank firms designated by the Financial Stability Oversight Council.

Referring to the Volcker Rule, Lew said, "I will continue to push for swift completion of a rule that keeps faith with the intent of the statute and the President's vision."

The stakes have been high for both banking and market regulators given the complexity of the trading ban. Speaking about the Volcker Rule, Tarullo said in public remarks July 15 that it was important for the agencies "to provide firms, markets, and the public with the product of all this work, so that they can begin to adjust their plans and expectations accordingly."

But some are still skeptical about whether regulators are near the finish line on Dodd-Frank implementation given the number of times they have said rules were "coming soon."

"This is yet another July heading into vacation, heading into September, heading into the fourth quarter with none of the major interagency rules seemingly any closer to finalization than they were in 2010," said Karen Shaw Petrou, a managing partner at Federal Financial Analytics Inc.

Coordination was a hallmark of Dodd-Frank. Lawmakers had hoped interagency rules would help balance the strong competing interests of various financial sectors. It also represented a departure from the days when banking agencies voluntarily agreed to write capital rules jointly but were not forced to do so under law.

Even now, agencies could split off from the joint Dodd-Frank discussions if they chose. In certain cases, the law allows any agency to go ahead and write rules pertaining to institutions it alone supervises if cooperation broke down. But for the most part, regulators have remained committed to joint rules. In discussing Volcker, for example, regulators have noted that they could proceed with the rule separately, but have declined to do so in order to avoid inconsistences.

But complicating the process even more is that it is not just the three bank regulators the Fed, FDIC and OCC needing to sign off on a rule. And within some agencies, a board must approve every decision. The Fed, FDIC, SEC and CFTC have a combined total of 22 individual board members, each with individual perspectives.

Some have criticized the Treasury Department, in its role chairing the FSOC, for failing to step in often enough to force a decision when disagreements over how to proceed with rulemakings have stalled the process.

While the council has held dozens of meetings that have sometimes revealed themselves to be contentious, "Treasury does not come in and say, 'Here's the deal we should take, tell us right now why not?' Divide them into winners and losers and move the process forward," Petrou said.

Others agree, saying FSOC has lacked necessary strength to intervene. Stanley said the council and the administration have not made "trying to keep the implementation process on track a priority."

But others said more involvement by Treasury would be difficult, given the amount rules Dodd-Frank required and the administration not wanting to be viewed as overruling independent agencies.

"It's not just a process thing with FSOC," said Randall Kroszner, a former Fed governor and now a professor at the University of Chicago. "There is an astonishing amount of rules to be written in a very short period of time, which would strain any system for a single regulator."

Some say that given the amount of work left to regulators, expectations for how quickly they could get through it all should have been tempered.

"We shouldn't be surprised that it's taken so long," Elliott said. "We're making a very wide set of far-ranging changes to the financial system. Dodd-Frank is quite lengthy, but also leaves a tremendous amount to the regulators to go beyond that, and we do have a regulatory system with too many different agencies in addition to the need to coordinate internationally."

Not everyone agrees that a group approach to writing rules is the best method.

"I don't think we actually get better rules that way," Elliott said. "In theory, having more voices will help, but we don't usually assume a committee will do a better job than a few smart people working together."

The regulatory quagmires following the law's enactment raise the question of whether a mandate of writing rules jointly will ultimately be viewed as a benefit or a cost of the regulatory reform effort.

Volcker has voiced his own criticism, suggesting on May 29 that too many agencies jointly implementing Dodd-Frank has been a "recipe for indecision, neglect and stalemate, adding up to ineffectiveness."

Tarullo says he will reserve his own judgment, for now.

"We'll have to wait until the whole process is over for more objective observers to ask the question on net: has the value of different perspectives been such as to make that kind of rulemaking with multiple agencies the best way to go?" Tarullo said. "I think it's a little early to judge yet, but I think it's undeniable that the feature of Dodd-Frank is part of what has slowed down the rulemaking process."