-

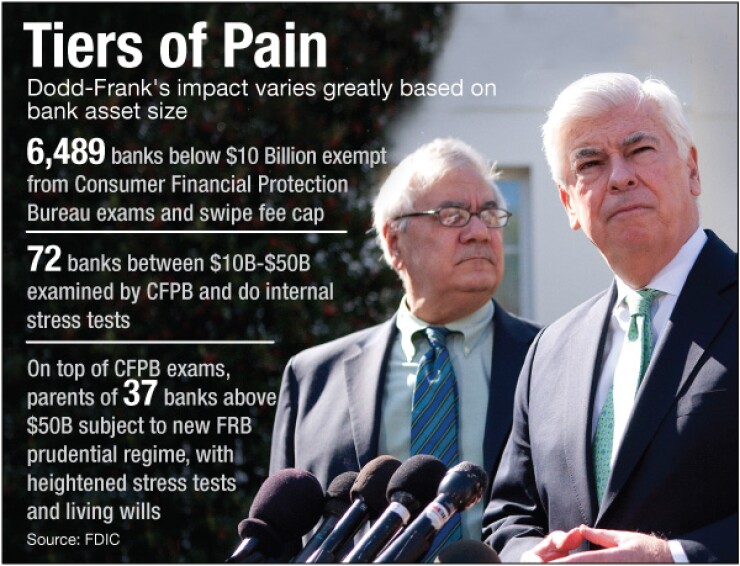

The focus on raising the $50 billion-asset threshold determining which banks face the toughest provisions is highlighting interest in letting more community banks enjoy exemptions written into the law.

January 23 -

There's a growing push to revisit how banks are determined to be "systemically important" under the Dodd-Frank Act, but questions about how to resolve the problem still loom large.

October 8 -

In a broad-ranging Q&A at American Banker's Regulatory Symposium, Comptroller of the Currency Thomas Curry questioned the asset threshold used to subject larger banks to enhanced rules, and discussed examiners' concerns about the "culture" at banks.

September 23

WASHINGTON The ranks of policymakers pressing Congress to increase the $50 billion "systemic" threshold for large institutions is continuing to swell, but there is a faster method a little-noticed provision of the Dodd-Frank Act that allows regulators to act on their own.

The 2010 regulatory reform law specifically created the $50 billion limit, above which all banks are considered "systemically important" and subject to enhanced supervisory and capital standards. But Dodd-Frank also empowers the Federal Reserve Board acting on the recommendation of the Financial Stability Oversight Council to raise the threshold on its own for certain standards.

Regulators have not said whether they would act on their own, but several top officials, including Fed Gov. Daniel Tarullo and Comptroller of the Currency Thomas Curry, have already expressed their concerns about the current threshold.

"The question is whether the Fed would want to address this issue itself or leave it to Congress," said V. Gerard Comizio, a partner at Paul Hastings. "For the Fed, this may be a question of the efficient allocation of supervisory resources where they are most needed."

Some observers said, however, that regulators may prefer to leave the issue to Congress. They point out that the central bank's authority to raise the threshold is only limited to certain standards of the law. Setting a new threshold would also effectively create new winners and losers for firms that still exceeded the cutoff, creating a controversy supervisors would rather avoid.

"There will be constituencies that want that threshold in different places. Who wants to make that decision?" said Oliver Ireland, a partner at Morrison Foerster and a former Fed attorney. "The regulators might say to Congress, 'We'd rather you pick the asset threshold.'"

Some said that attempts by the FSOC and Fed to raise the threshold could also throw cold water on efforts to make broader changes to the supervisory regime for systemically important firms.

"I would much rather see a fundamental debate in Congress as to where [the threshold] should be than have the regulators move unilaterally," said James Thomson, a professor at the University of Akron. "Is it better than nothing to have the regulators do it? Yes. But if the regulators' moving unilaterally prevents other needed reforms from happening, then that's the downside."

The $50 billion figure is already increasingly in the crosshairs. Lawmakers in both parties, including the Senate Banking Committee's top Democrat, Sherrod Brown, say it unjustly burdens midsize banks that exceed the threshold but are not truly a systemic threat. A bill proposed by Rep. Blaine Luetkemeyer, R-Mo., would get rid of all numeric thresholds, while an idea floated by the Bipartisan Policy Center would raise the cutoff to $250 billion.

Even regulators strongly in support of the tough supervisory standards have suggested the Dodd-Frank cutoff was set too arbitrarily.

"The key question is whether $50 billion is the right line to have drawn," Tarullo said in a May speech. "Experience to date suggests to me, at least, that the line might better be drawn at a higher asset level $100 billion, perhaps."

The law grants authority to the FSOC to recommend that the Fed raise the threshold as it relates to certain standards outlined in "Section 165" of the law. They include requirements that companies increase their contingent capital, draft resolution plans known as "living wills" and credit exposure reports, limit concentrations, enhance public disclosure and curb short-term debt. But that authority does not extend to other significant requirements, including rigorous stress tests and general risk management standards. (Regulators are barred from lowering the threshold.)

To date, it is unclear whether the council plans to take such a step.

A source familiar with the internal deliberations of the council, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, said such a recommendation up to this point has not yet been seriously considered since some of the Section 165 rules are still being implemented.

"The staffs of the member agencies of the council have discussed this authority to recommend raising the threshold, but it has been important to give the regulators time to develop the rules required under the statute," the source said.

But at least the Fed and the Office of the Comptroller of the Curry already appear to have misgivings about the current $50 billion cutoff.

"Fifty billion dollars [in assets] was a demarcation at the time" but "it doesn't necessarily mean you're engaged in that activity that they are trying to target," the OCC's Curry said at American Banker's regulatory symposium in September.

He said a "better approach" would be for regulators to go beyond the cutoff and determine the scope "based on the risks in their business plan and operations.

"It's just too easy to say, 'This is the cutoff.' I'm a little leery of just a bright line," he said.

But whether they would support acting without Congress is a different question. Barney Frank, the former chairman of the House Financial Services Committee and a co-author of Dodd-Frank, agreed the limit should be increased, but said the issue should be left to Congress to decide.

"I think the $50 billion ought to be at least indexed, so I think for the regulators to do it only I think it would be better to look at it overall," said Frank in an interview. "I'd rather do it legislatively."

But getting a law passed could be tricky. Some Democrats fear that further reopening the law risks more wholesale changes. In his State of the Union address, President Obama said he would veto any further "unraveling" of Wall Street rules. It's unclear whether raising the threshold would qualify.

In contrast, a quick move by the FSOC in concert with the Fed would allow more banks to avoid the new prudential regime without a prolonged legislative debate.

"At least as the law is written, the FSOC could vote to raise that number," Comizio said.

He noted that the Fed staff has signaled recently that the breadth of institutions currently eligible for the new supervisory standards puts a potential strain on the agency's resources, limiting its ability to focus on the biggest firms.

"I would be surprised if there were any agencies that would object to that number being raised, especially since the main player with respect to the large [systemically important financial institutions] the Federal Reserve Board seems to be more concerned about concentrating resources on the biggest institutions," he said.

But others said Congress is much better positioned to adjust the number. From all signs, there is bipartisan support for a higher cutoff, and supporters of broader legislative changes to Dodd-Frank are hopeful that the asset threshold issue could prompt discussion around a corrections bill.

"I still think of the SIFI asset threshold as being the backbone of any Dodd-Frank legislative fix this term," said Isaac Boltansky, an analyst at Compass Point Research & Trading. "You take that out of lawmakers' hands, and it further lessens the effort for a broader fix, because there's less agreement."

A congressional fix could also take into account whether the threshold should be raised for additional aspects of the Fed regime, such as the stress test requirements.

"It's cleaner with a legislative solution," said Edward Mills, a policy analyst at FBR Capital Markets. "You get a clearer sense as to what the intent of Congress is ... you get a threshold of what the dollar amount should be set at now, and what standards should be included and excluded for these institutions."

Boltansky noted that the Fed has previously been shy to act unilaterally on changes to policy related to Dodd-Frank. When some lawmakers had urged the central bank to be flexible with insurance companies under a provision imposing stricter capital requirements on big financial services companies, the agency still waited for Congress to act.

"The Fed's seemingly taken a narrow view of the legislative authority in certain areas of Dodd-Frank," Boltansky said. "They'd much rather have Congress change the threshold."