A section of the law rolling back key Dodd-Frank Act provisions could help small banks in need of funding.

Embedded in the nearly 200-page document is a change to how banks report reciprocal deposits, or those that a bank, with certain conditions, can hold with help from a placement network. Under terms of the law, reciprocal deposits at well-capitalized banks with a Camels rating of 1 or 2 can total the lesser of $5 billion or 20% of total liabilities.

That's welcome news for institutions such as FVCbank in Fairfax, Va., which relies on reciprocal deposits to compete with larger banks, said Patricia Ferrick, the $1.1 billion-asset bank's president. The product provides security or comfort to customers who may be concerned about parking large sums of money with smaller banks, she added.

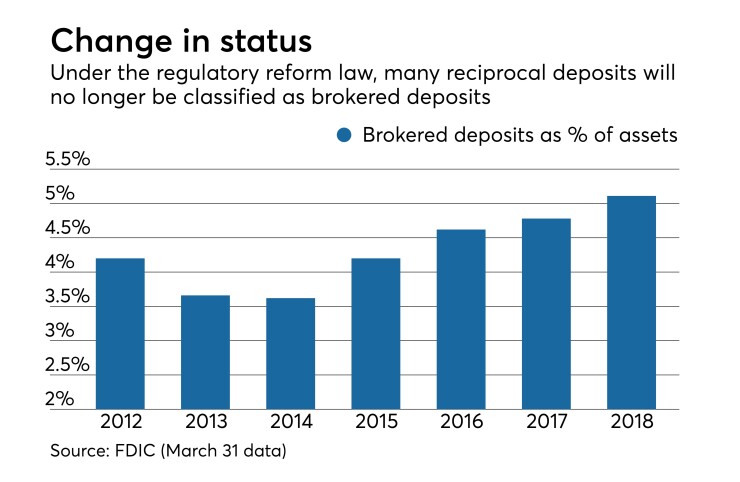

The change could provide an even bigger lift to banks that have used the product sparingly because regulators had required them to report reciprocal deposits, which exist to guarantee deposits over the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.’s $250,000 insurance limit, as brokered deposits. Regulators view brokered deposits with more skepticism than core deposits; banks that rely on those deposits pay higher deposit insurance premiums.

“This is probably some of more beneficial legislation we’ve seen in the last couple years,” said Mark Merrill, president and CEO of Old Dominion National Bank in Tysons Corner, Va.

Community bankers assert that reciprocal deposits are a secure funding source.

Most reciprocal deposits are from local clients with real relationships with the bank, said Christopher Cole, senior regulatory counsel for the Independent Community Bankers of America. He said the reform law removes some of the stigma tied to reciprocal deposits. Some bankers were wary about reciprocal deposits because a downgrade in their institution's Camels rating would give regulators an opportunity to question its brokered deposit volume.

The law “makes community banks more comfortable with using reciprocal deposits for funding and much less concerned about repercussions if they do [use them] and something happens,” Cole said.

About 80% of reciprocal deposits come from depositors located with 25 miles of the host bank’s office, according to Promontory Interfinancial Network, one of the leading placement networks for such funding. Promontory, which started offering reciprocal deposits by electronically trading pieces of large deposits to network banks in the early 2000s, said 1,170 community banks use such deposits.

FVCbank, for example, has many commercial and nonprofit clients that need to deposit large sums of money — but also want their money insured, Ferrick said, adding that about 11% of the bank’s deposits are reciprocal deposits.

“We always considered those core customers, even though we reported them one way,” Ferrick said. “Reporting it this way [under the new law] more accurately reflects our deposit base.”

About a tenth of Old Dominion’s liabilities are reciprocal deposits, Merrill said. The law gives the bank an opportunity to increase its volume of reciprocal deposits.

“Right now, we're being very selective as to the customers we put through the program, knowing that our capacity is limited,” Merrill said.

Not all bankers are as pleased with the legislation.

The law does not go far enough, said Andrew West, president of Eagle Bank in Polson, Mont. Despite the changes, Eagle would still have to report $13 million of reciprocal deposits as brokered deposits, he said.

“It doesn’t make a lot of sense,” West said. “Where did they come up with that arbitrary 20% of total liabilities?”

The $70 million-asset Eagle has a large percentage of reciprocal deposits because it is owned by a Native American tribe with large deposit needs, West said.

“They're not going to pull this money out of the bank and sink us,” West said. “They own us.”

West argued that regulators should differentiate between noncore and core deposits.

Cole said he expects the FDIC will define core deposits at some point, though it will likely take a while for the agency to make that differentiation. He said reciprocal deposits make up less than a fifth of total liabilities at most community banks.

For now, most bank watchers believe labeling up to 20% reciprocal deposits as core deposits will help smaller banks compete.

“The brokered label has certainly frightened off some institutions,” said Mark Jacobsen, Promontory's president and CEO. The law “more easily allows them to use a tool that’s been available to them for some time now to help compete with larger banks."