With the election of Democrat Phil Murphy as its next governor, New Jersey inched closer to becoming the second state in the country to establish a state-run, taxpayer-owned bank.

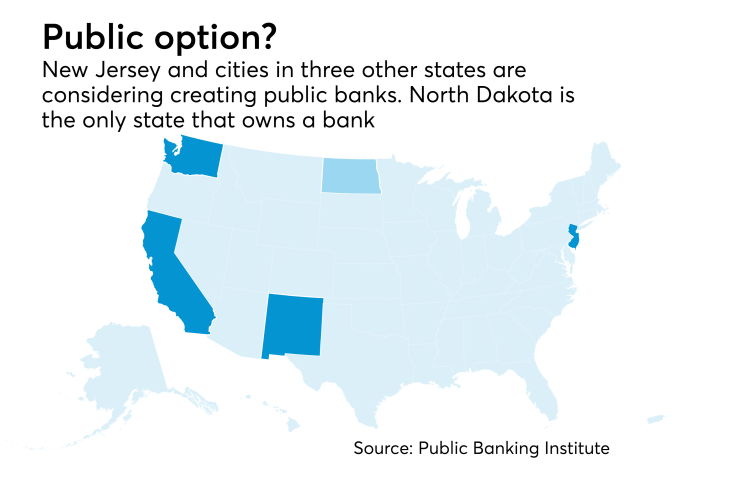

Murphy, a former Wall Street investment banker, is among a growing number of progressives who support the creation of more public banks as vehicles for funding infrastructure projects and stimulating economic development in underserved neighborhoods. Though efforts to create public banks in other states have failed in recent years, Murphy’s resounding defeat of New Jersey’s lieutenant governor in last week’s election — in a state where the legislature is already controlled by Democrats — is being seen as a much-needed shot in the arm for the broader public-bank movement.

“It’s not only a win for Murphy, it’s a win for public banks,” the Public Banking Institute, a nonprofit that advocates for the creation of public banks, said on its website following Murphy's victory.

Under his plan, tax and fee revenue the state collects would be deposited in the bank and then used for a variety of purposes, from providing low-cost loans to small businesses and college students to funding community development in areas that “are often ignored” by mainstream banks, Murphy said on his campaign website. A public bank would also create another infrastructure-funding option for cities and towns that might otherwise turn to “costly Wall Street bond markets.”

The proposal, as well as similar efforts in other states, face myriad hurdles, the biggest being stiff opposition from the banking industry.

The New Jersey Bankers Association is concerned that many small banks would lose out on municipal deposits that they use to lend in their communities. Michael Affuso, the trade group’s director of government relations, said that more 100 banks in the state are licensed to accept municipal deposits.

Affuso also drew a sharp contrast between New Jersey and American Samoa,

“I don’t like to pick fights, so I’m not willing to say its mere existence is awful,” he said. “However, its existence, depending upon how it’s created and what it is, could become a potential competitive threat to the banks in New Jersey. It’s not that we’re against competition, but we’re against government competition.”

Murphy has said that a public bank would complement, not compete with, local banks and credit unions. His gripe is with large out-of-state banks, because the state "has no control" over how they spend state funds. As an example, he noted that one unnamed bank accepted more than $1 billion of public deposits last year but made only three loans in the state through the federal government’s small-business lending program.

Murphy’s victory is one of several recent developments that have given hope to advocates of public banks. California State Treasurer John Chiang recently proposed a feasibility study of a public bank as one option for providing the

Funding a safe banking option for marijuana-related businesses, plus its intent to cut ties with Wells Fargo, also motivated the Los Angeles city council to greenlight its own feasibility study last month.

Public bank advocates are hopeful that better education around the issue, along with a few high-profile wins, will sway the court of public opinion in their favor.

Ellen Brown, the founder and chair of the Public Banking Institute, estimates she’s talked with about 20 different groups nationwide that are actively exploring options for creating public banks. Serious efforts to study the issue are also underway in Santa Fe, Seattle and Oakland.

“It seems to me that right now the biggest challenge is fear, based on a lack of education, that the local mayor or the governor or the state treasurer is going to run a bank and they’re not trained to run a bank,” said Debra Figart, a professor of economics at Stockton University in New Jersey. Figart said that as more people learn about

In North Dakota, all state money, mainly taxes and fee revenues, are deposited into the state bank. The state insures those deposits itself, rather than obtaining insurance from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., and those funds are used to make low-cost loans to the agricultural industry, small businesses and college students.

Founded in 1919, the Bank of North Dakota is governed by an industrial commission made up of the governor, state attorney general and agricultural commissioner. The bank also has an advisory board, which is required to have at least two officers of North Dakota banks, and an executive committee made up of seven corporate-level officers at the state bank.

Still, bankers counter that North Dakota’s economy is vastly different than economies of other states where public banks have been proposed.

Massachusetts conducted its own feasibility study in 2011, but ultimately chose not to pursue creation of a state bank. The authors of that report cited the significant initial capital investment as an obstacle and said it made more sense for the state to work within the banking system.

Massachusetts is home to more than 180 state-chartered banks and credit unions, and several of the nation’s largest banks, including Bank of America, Citizens Financial Group and TD Bank, have significant operations there.