Regulators need to give banks a kick in the pants to confront business risks posed by climate change, according to a new report out of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission.

Federal agencies — and banks themselves — should conduct stress tests and other analyses

that measure the financial industry’s resilience to hurricanes, wildfires, floods and other natural disasters. Otherwise the economy could be subjected to shocks as devastating as the fallout from the coronavirus pandemic, the report said.

If the recommendations were to be adopted, banks in the short term would need to collect more and different kinds of data on their customers. In the longer term, lenders would have to make some tough decisions with respect to credit and underwriting practices.

“What strikes me in this report is the very detailed road map — we have the plans and we know what needs to happen to manage these risks, is what this report says,” said Emilie Mazzacurati, founder and CEO of 427, a Moody’s affiliate that specializes in climate risk. “Should this become a priority, there’s a very clear set of actions the market should expect to see from financial regulators and supervisors.”

U.S. regulators

The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, the Federal Reserve Board and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., all declined to comment on the report.

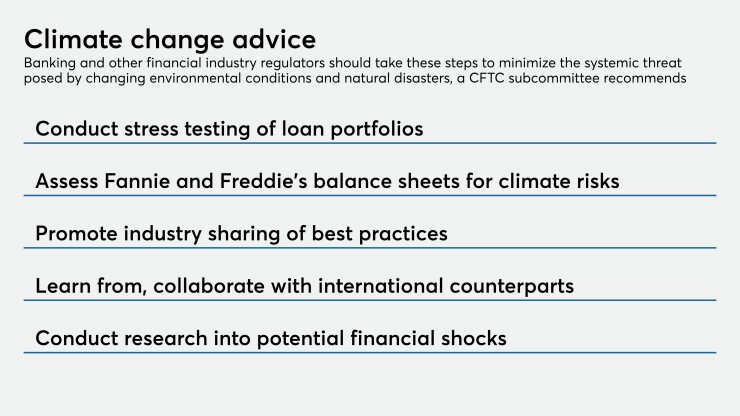

The subcommittee that wrote the report, which included several bankers and officials from the government and nonprofit sectors, outlined a possible stress-test pilot and urged regulators to study the steps already taken by central bankers in Europe and elsewhere.

The pilot should include agricultural and other community banks as well as regional banks, and it should test balance sheets against “plausible and relevant” climate scenarios, the report said. It should cover financial institutions’ responses to climate-related risks and opportunities over defined time horizons.

The report called for greater research into and attention to what it calls subsystemic shocks, or climate events affecting a particular geography, sector or asset class. An example of a subsystemic shock might be

“Subsystemic shocks related to climate change can undermine the financial health of community banks, agricultural banks, or local insurance markets, leaving small businesses, farmers and households without access to critical financial services,” the report said.

Besides stress tests, the subcommittee recommended that regulators promote information sharing across the industry and conduct greater research into climate-related shocks. This could mean banks would need to collect more and different kinds of data on their clients, especially commercial clients, and integrate that data into their risk management processes.

Climate-risk-related capital requirements could even be part of the discussion someday, the report said. It did not explicitly recommend special capital requirements, but the report said the Dodd-Frank Act gives regulators the authority to “prescribe more stringent prudential standards based on the riskiness, complexity, size and ‘any other risk-related factors the [Fed] Board of Governors deems appropriate.’ ” And that could include enhanced capital requirements.

The report also recommended that regulators assess the balance sheets of Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and other government-sponsored enterprises for climate-related risks. And it recommended that the Financial Stability Oversight Council — which includes banking and other financial regulators — incorporate climate risk into its regular oversight and reporting functions, coordinate information sharing across member agencies and develop a long-term research program on the subject.

Perhaps most notably, the report suggests that no congressional action would be needed to implement its advice. Regulators already have the authority to do many of these things under existing statutes and rules, the report said.

The industry has already gotten a small preview of what this kind of scrutiny might look like, said Paul Noring, managing director and leader of Berkeley Research Group’s financial institutions practice.

Regulatory attention to flood risk in general has increased over the last five to six years. In particular, regulators have begun to look more closely at flood risk in commercial portfolios, he said.

“More and more exams were focused on commercial, and banks’ processes around commercial just generally are not as strong on flood compliance as they are on the residential side,” Noring said. “More properties are being impacted by it. They maybe weren’t in an area that was typically thought to flood, but now you’re experiencing significant floods, which you hadn’t before.”

Mazzacurati, too, cited commercial lending as a vulnerability for the banking industry. While banks possess granular detail on the residential mortgage loans they originate, they may not necessarily know the location of every piece of property a large corporate client owns — let alone whether that property is at higher risk to damage from hurricanes, severe flooding or fires.

While acknowledging that climate change poses a real systemic threat to the industry, the Bank Policy Institute — a trade group representing 42 of the largest banks in the country — also identified a lack of data as one of the challenges to implementing stress testing.

“Stress testing for long-term climate change … is an extraordinarily complex and difficult endeavor given a lack of data, established modeling techniques and the need to forecast over longer time horizons than economic stress testing has ever contemplated,” the institute's president and CEO, Greg Baer, said in a statement.

The report urged greater disclosure across the financial sector, something that experts say is long overdue.

“We don’t know what we don’t know,” said Kristen Sullivan, a partner with Deloitte who leads the firm’s sustainability practice. “Absent effective and reliable disclosure around risk, the market’s not able to price risk.”

“Market participants need to understand the risks that are out there and need to have a framework to be able to manage the risk,” said Blaine Townsend, director of sustainable, responsible and impact investing with the investment management firm Bailard. “Regulators taking this step to identify the risks and create a road map to dealing with them is very important.”

David Reiling, CEO of the $1.4 billion-asset Sunrise Banks in St. Paul, Minn., said that without carbon pricing, another one of the report’s recommendations, efforts like stress testing may fall short of the broader objective. There are several ways to achieve it, but carbon pricing is a market-based strategy that essentially encourages companies to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions by making polluting more expensive. The Business Roundtable, a lobbying group made up of CEOs from some of the largest U.S. corporations,

“One underlying question I would have is if there’s a will to do it, politically, financially, socially in the U.S., specifically,” Reiling said. “I would even say that moving a regulator into this space, there really aren’t a lot of regulations to fall back on, other than general risk categories to the business model. There’s no climate or carbon metrics to be held accountable to.”

Mazzacurati says that in the long term, some of the stress testing and scenario analysis results may mean banks need to make some tough choices about underwriting certain loans. If borrowers in certain regions cannot obtain fire insurance, for example, that may lead some banks to decide it simply isn’t worth the risk of lending in those places. Reviewing the aggregate risk across their own portfolios could also eventually lead banks to price certain loans higher to reflect climate-related risks, she said.

The report’s authors emphasized that its recommendations are merely a starting point for understanding and preparing for the potential risks of more severe weather events.

In introducing the report, subcommittee chairman Bob Litterman, risk committee chairman and a founding partner at the registered investment adviser Kepos Capital, drew a direct comparison to the pandemic in warning about the consequences of inaction on climate change.

“