-

At least three serial consolidators are positioning themselves for more deals should the right opportunity arise. SCBT and Iberiabank filed shelf registrations this month, while Wintrust raised $127 million.

March 26 -

PSB Bancorp in Wisconsin is requiring Marathon State Bank to pay out a special dividend before the deal closes. While unusual now, the move harkens back to a pre-crisis tactic that existed when capital wasn't a concern.

March 21 -

Four community bankers on the hunt for acquisitions warned prospective sellers that they will have little say in how much they get paid.

November 10

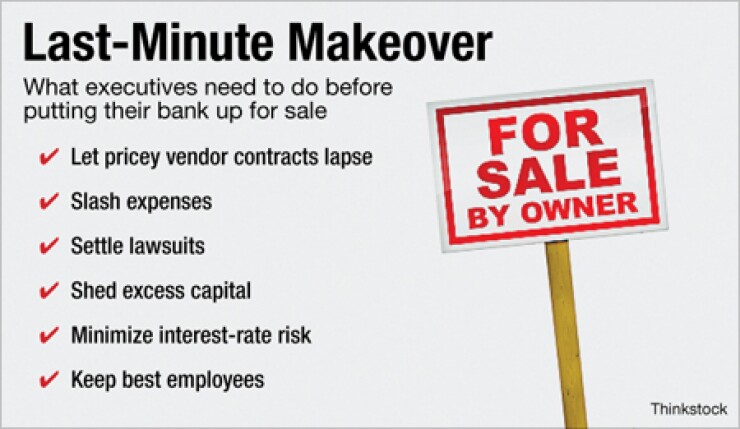

Credit quality is the No. 1 thing on bank buyers' minds, but that doesn't mean they don't have other things on their checklist.

Like on television shows that help homeowners stage their abodes to increase curb appeal, there are things that banks on the hunt for a buyer must do to prepare for a sale, experts say. It is insufficient to fix the proverbial roof; buyers want a working toilet, too.

As credit quality improves, experts say, once secondary considerations are becoming more important. Being proactive can help a seller stand out among all the others on the block, and it could also help them eke out a better deal.

"If the bank has crossed that mental hurdle and decided to sell, their goal is to maximize shareholder value," said

Perhaps the easiest step is to avoid entering into any long-term contracts involving data processing, core systems or real estate. Those contracts tend to have large breakup fees, and the cost falls to the seller to resolve, said Jeffrey C. Gerrish, a partner at Gerrish McCreary Smith.

Lee said he advises clients that are bent on selling to enter into short-term contracts, even if they are more expensive up front.

"In a small bank, it can be a material impact," Lee said. "As the seller, you could be on the hook for tens of thousands of dollars."

The observers also suggested cutting expenses, but that should be handled with care. Lowering expenses can help raise earnings and ultimately the price of the deal, but buyers can tell when the cuts are justified or if they are window dressing.

"All banks are looking hard at expenses, but it can backfire," Lee cautioned. "If it is so dramatic, the buyer sees it as an obvious ploy that can jeopardize the revenue stream."

Chris Myers, the president and chief executive of CVB Financial (CVBF) in Ontario, Calif., agreed that cost cuts get sellers closer to the "true value" of their institution but offered one warning: Banks should offer incentives to star employees to stick around.

"Do what you can to retain the talent," Myers said. "If you have a niche business that is driven by a couple of key individuals, do what you can to make sure they don't walk out the door when they find out you are planning to sell."

Retention bonuses for top sellers and some executives are common, Lee said. Such bonuses do not guarantee that the talent will stay when the ownership change happens, but it keeps them at least until the purchase closes.

"I say go to the key producers and tell them, 'We are going to sell the bank, but we want to protect you'," Lee said. "You need a commitment for them to stay put."

Myers is currently on the hunt for acquisitions; his $6.5 billion-asset company has a track record of acquiring a bank once every two years or so, but it has been nearly three since the company has announced one.

"The asset quality game is dissipating. There are trends we can rely on now," Myers said in an interview. "We are looking pretty hard, but as we peel back the onion, there are all these other things that are becoming concerns."

Myers is particularly concerned with interest-rate risk in securities portfolios at targets. With an abundance of deposits and hardscrabble loan growth, more banks are increasing the size of their securities portfolio. He wants to know how many of those deposits are sticky and how many could flee when interest rates rise.

"I'm looking at the sustainability of the cash flow and the risk involved in the cash flow," Myers said. "My focus is on the quality of your funding."

He said he is also not looking for a bank whose balance sheet has swelled because of securities.

"If I'm looking at a $700 million-asset bank, with $250 million in securities, what am I really buying here? I don't want to pay for a bank because they have securities," he said.

Though sellers should be mindful of interest-rate risk, making over the securities portfolio to tailor a sale is probably too aggressive, Lee said.

"Every bank has a different philosophy about their securities portfolio," Lee said. "It is really hard to anticipate what the buyer wants, so I just say to practice prudent interest-rate risk modeling."

Gerrish also said that sellers should look for ways

Additionally, Lee and Gerrish said, banks should put their regulatory and legal affairs in order. Acquisitions are time-consuming, they said, and such matters only add uncertainty to the process. "Make sure you are up to scratch with the regulators on everything. Don't leave any settlements on the table. Don't fight for nine months for that last 10 cents," Lee said. "The goal is to get everything cleaned up and resolved."