-

Visa lost a lot of PIN debit business after new regulations took effect this year, but the payments network insists it has stanched the bleeding and its incentive programs will win back market share.

August 10 -

The company's fixed network fee penalizes merchants that route debit transactions to any competing network, and subverts the competition that the Durbin amendment was designed to foster.

June 26

"Debit or credit?" That's a familiar refrain for debit card users upon deciding whether to key in a PIN or sign for a purchase.

But the question is also an increasingly important one for banks adjusting to new rules that capped interchange fees and transformed the economics of the debit card business.

Whereas banks used to encourage customers to make higher-revenue signature transactions on their debit cards, even using

"From an issuer point of view, they would like to see a lot more PIN transactions," says Ed Lawrence, director of Auriemma Consulting Group.

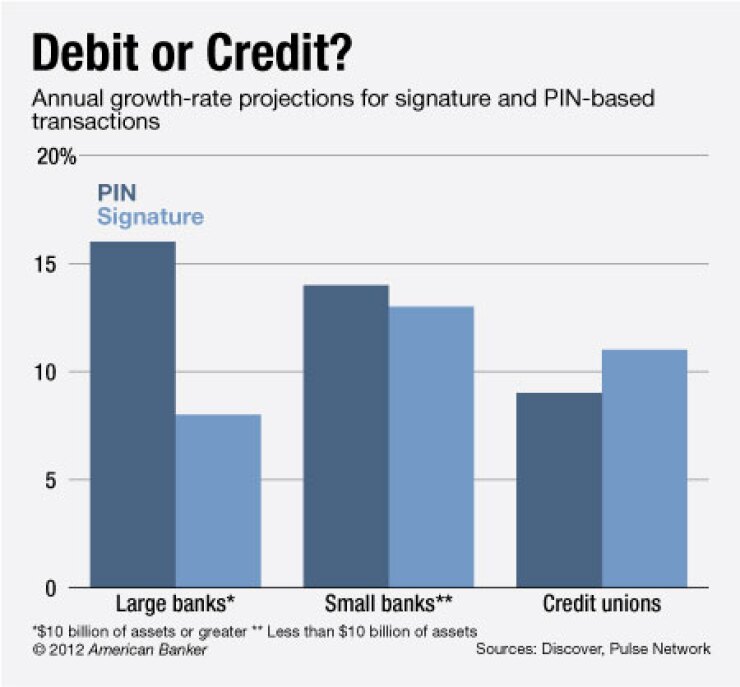

A study released earlier this month by Discover's PULSE pin-debit network found that some issuers are even actively looking to move debit card users from signature to PIN, which accounts for about one third of the overall debit market right now.

"The signature-centric approach has been abandoned by many regulated issuers," says an executive summary of the study, which was conducted by consultancy Oliver Wyman. More than two dozen issuers now regulated under the interchange cap were surveyed for the study, along with 30 smaller credit unions and banks exempt from the rule, which applied only to institutions with at least $10 billion of assets.

"'We need to move from signature to PIN. We may have some sweepstakes for PIN transactions,'" said one unnamed issuer subject to the interchange cap, said in the study.

"We have been aggressive with contacting customers with phone and direct mail to promote PIN,'" added another.

With signature and PIN interchange rates now roughly on par, issuers are looking at the lower cost structure of PIN, says Steve Sievert, executive vice president of marketing and communications at PULSE.

"There's the fraud component — a lower risk profile associated with PIN," he says. "When you combine lower fees for processing with lower fraud losses, the economic profile is stronger."

But consumer habits are hard to break, and it's still not clear how effective issuers' efforts will be, especially after they spent years trying to convince customers to sign for purchases instead of using a PIN.

There was no change in the proportion of business conducted using PIN between 2010 and 2011 among issuers affected by the interchange cap, according to the PULSE study. The cap went into effect in the fall of 2011.

"From a consumer point of view, you've got to look at the reasons why people don't use a PIN," says Auriemma's Lawrence. "They don't like others looking over their shoulder. It's a secure transaction, but it makes people feel a little uneasy."

Moreover, some who were used to signing for purchases may have forgotten their passwords, he adds.

"What message do you use, what incentive are you giving to the consumer to use the PIN? You say there's less fraud, but does fraud really upset the consumer? Basically there's zero liability for them" in cases of fraud, he says.

Banks also have to contend with another complicating factor: Merchants now have more control over routing decisions thanks to a second part of the Durbin Amendment that went into effect in April. Issuers must process debit card transactions over at least two networks, which puts the routing decision in retailers' hands.

Moreover, some smaller merchants don't have PIN pads set up, and there's currently little incentive for them to add one.

"From a merchant point of view, if they look at this as a better way of doing business, they'll bring pin pads in," says Lawrence. "Merchants who don't have pin pads today, what incentive do they have to bring a pin pad in?"