-

Many problems with payday products are concocted by activists and politicians with mercenary intent who are more interested in squelching innovation than letting people make choices for themselves.

February 20 -

The traditional payday loan structure should cease to serve as the standard by which innovation in this credit space is measured.

February 12

Storefront payday lenders are making a combative new pitch to state lawmakers as they push for an expansion of short-term, high-cost lending in states across the country. Their message, in essence: if you don't allow us to do business, our would-be customers will find shadier sources of credit on the Internet.

"We see on the television commercials from other companies that are preying upon these people," Trent Matson, director of governmental affairs at Moneytree Inc., a payday lender that operates in five states,

That argument elicits cackles from consumer advocates, but it is echoing through legislatures in states that have banned or restricted storefront payday lending. At least three states — including Washington, North Carolina and New York — are now considering lifting their bans or easing restrictions on the theory that if consumers are going to obtain payday loans anyway, they might as well use an outlet that gets licensed and pays state taxes. Similar pieces of legislation are expected to be filed in Arizona and Pennsylvania.

Traditional payday companies are licensed to do business in more than 30 states, while Internet-based lenders — some of which operate from overseas — often lend in the states where laws prohibit payday loans.

Storefront lenders, which have long been portrayed by consumer advocates as the bad guys, argue that they're abiding by the law, and their upstart challengers often do not. The mud is flying in the other direction, too, with online lenders claiming that traditional lenders are trying to thwart competition.

"The industry is changing. And those who cling to a dying business model look for ways to preserve it," says a source from the online payday industry, who asked not to be identified.

Payday lending is a roughly $7.4 billion-per-year industry and an estimated 12 million Americans take out payday loans each year.

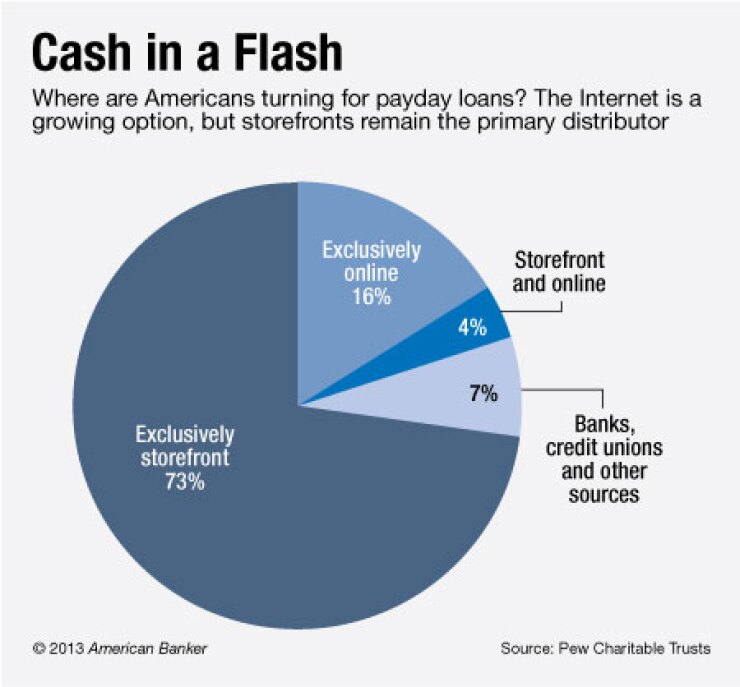

No one knows exactly how much payday lending takes place on the Internet, in part because some of the industry operates in the regulatory shadows. In late 2011, 16% of U.S. payday borrowers said they were getting their credit exclusively online,

In states that are considering changes to their payday lending laws, the question of whether bans are driving would-be storefront customers to online borrowing has become a key point of dispute.

Consumer advocates, who've long accused payday lenders of trapping poor people in a cycle of debt, say the state bans have done what they were intended to do.

Last year's Pew study found that the percentage of U.S. adults who took out payday loans from brick-and-mortar stores was four times as high in states that permit the loans as it was in states that ban or significantly restrict them. The amount of online lending was slightly higher in the states that ban or restrict payday loans than it was in states that permit them, but not by a statistically significant amount, according to the report.

"So the notion that people are flocking to the Internet," says Sarah Ludwig, co-director of the Neighborhood Economic Development Advocacy Project in New York City, where payday loans are banned, "because they can't find a loan at their storefront payday lender is complete nonsense."

"The states that have legalized payday lending — what do they get? They get more payday loans," adds Uriah King, director of state policy at the Center for Responsible Lending.

The Pew research also suggests that bans on payday lending may be advantageous to those banks and credit unions that are interested in offering small-dollar, short-term consumer loans at lower interest rates. The report found that 44% of storefront payday borrowers say they would turn to a bank or credit union if payday loans were unavailable.

When representatives of the storefront payday industry are pressed, they acknowledge that state bans lead to fewer overall payday loans. But they dispute the size of the effect.

Jamie Fulmer, senior vice president of public affairs for Advance America, a payday lender that operates in 29 states, questions Pew's numbers and favorably cites

"State prohibitions do not necessarily prevent all state residents from getting a payday loan, since people can get payday loans via the Internet or go across state lines to obtain the loan," that report stated, drawing on state-by-state survey data.

Traditional payday lenders have long argued that banning payday loans will simply drive the business to nearby states. Today in North Carolina, where payday lenders are seeking to overturn a ban on their industry enacted in 2001, that old argument is being married to the newer one.

"Because online lenders operate outside of the jurisdiction of state regulators, they often charge higher fees and offer none of the consumer protections regulated lenders provide," advocates of bringing payday lending back to the Tar Heel State wrote on a website they established to rally support.

The North Carolina legislation, which

Pennsylvania is another state where storefront payday lenders have been seeking to overturn a ban. Last year, the sponsor of legislation that sought to legalize payday lending tried to solicit co-sponsors with the argument that Internet loans are impossible to regulate.

Washington state currently allows payday lending, but its stores operate under tighter restrictions than in many other states. For example, borrowers are only allowed to take out eight payday loans a year.

Now the storefront payday industry is backing two bills that would give it wider latitude under Washington law. One of the measures has passed the state Senate and is awaiting action in the House.

During a legislative hearing in January, Moneytree's chief executive officer, Dennis Bassford, noted that his company pays taxes and employs 500 people statewide, drawing an obvious contrast with online competitors.

"I can assure you there are Internet lenders from all over the globe who do make these loans illegally to Washington consumers. And let me be clear: the illegal online lenders are rampant in this state," Bassford said.

The lines between traditional payday lenders and online operators are not always clear. Some companies operate in both spheres. And among online lenders, some companies will not process applications from states that ban payday lending, while others will.

"It's really on a company-by-company basis as to how they do that," says Peter Barden, spokesman for the Online Lenders Association, whose members include both lenders and lead generators.

So what are the repercussions of taking out an online payday loan in a state where the product is illegal?

Storefront payday lenders warn that online borrowers are susceptible to great risk, and customers who are wary of borrowing online

But consumer advocates say the online loans are not legally collectible in states that ban payday lending. Their position got support last month from New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, who

Instead of simply playing defense at the state level, the online payday lenders are taking their case to Washington, D.C.

"We think a state-by-state approach makes it difficult for this emerging nonbanking industry to create innovative products that consumers are now demanding," says Barden of the Online Lenders Alliance.

But the measure faces an uphill fight. Last year it failed to get a committee vote, and it was dealt another setback in November when Democratic co-sponsor Rep. Joe Baca lost his reelection bid. The bill's backers plan to introduce it again, but it is hard to imagine the legislation gaining traction during President Obama's tenure.

The main trade group representing storefront payday lenders, the Consumer Financial Services Association, has not taken a position on the federal charter bill, according to spokeswoman Amy Cantu.

She quickly adds: "And we are very happy working with our state lawmakers and regulators."