The payday loan chain ACE Cash Express had a brief moment of notoriety in 2014, when

Surprisingly forthright, the graphic depicted the cycle of debt for which payday lenders frequently get criticized. It suggested that Irving, Texas-based ACE

Almost two years later, when Google banned ads for U.S. loans with annual percentage rates above 36%, the tech giant cited the payday lending debt cycle as

Google’s 2016 ban drew praise from consumer advocates and civil rights groups, along with jeers from one then-executive at ACE Cash Express.

“Extremely disappointed,”

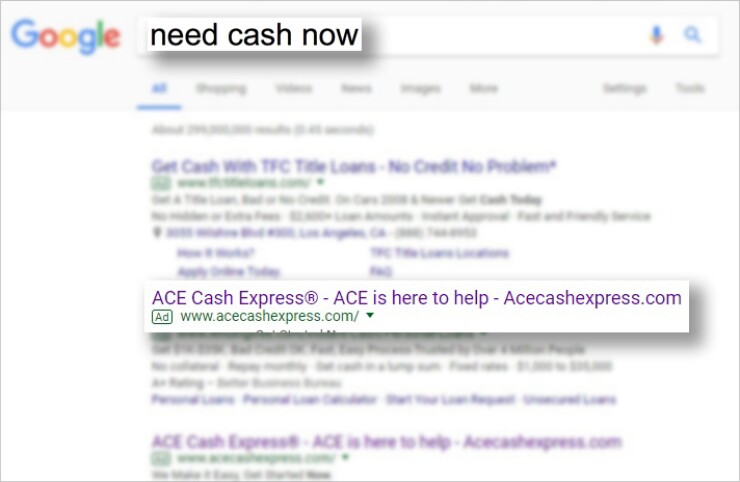

But as it turned out, there was less to the Google ban than initially met the eye. A year after it took effect, American Banker found numerous ads on Google from ACE Cash Express and other payday lenders, often on the first page of search results.

Some of the ads appeared to be clear violations of

In short, payday lenders have found multiple ways to get around Google’s year-old ad ban. Similarly, the payday industry has dodged the rules in

“Subterfuge is as core to the payday lenders’ business model as is trapping borrowers in a cycle of debt,” said Diane Standaert, director of state policy at the Center for Responsible Lending.

In late September, American Banker sent screenshots of payday ads found on Google to the Mountain View, Calif.-based company. After an internal review, a Google spokeswoman said that the ads in question violated the company’s policy.

“While we do not comment on individual advertisers, we have reviewed and removed the ads in violation of our policy on lending products,” the spokeswoman said in an email.

Google declined to answer questions about the details of its payday loan ad ban, the steps the company takes to enforce it, or the ban’s effectiveness.

Exploiting a loophole

Loan sharks in 2017 operate mostly online. Because the Internet is borderless, companies can set up shop overseas and make loans to Americans without regard to federal and state consumer protection laws.

Online payday lenders typically charge higher interest rates than in-store lenders, according to

Pew found that 30% of online payday loan borrowers reported having been threatened by a lender or a debt collector. It also determined that advertisers were typically paying $5 to $13 per click on online loan ads. That is a hefty price, given that a click does not necessarily translate into a loan.

Google, which collected a whopping $79 billion in ad revenue last year, has made a lot of money from the clicks of cash-strapped consumers. So the search giant was acting against its own financial self-interest when it announced plans to crack down on payday loan ads.

The policy, which was announced after the company consulted with consumer groups, had a similar rationale as the Silicon Valley giant’s rules against advertisements for guns, ammunition, recreational drugs and tobacco products.

“We don’t allow ads for products that we think are excessively harmful,” Vijay Padmanabhan, a policy adviser at Google, said in June 2016.

The Google ban covers all U.S. personal loans with annual percentage rates of 36% or higher, a category that includes both payday loans and high-cost installment loans. Personal loans that require repayment in full in 60 days or less are also subject to the ban.

“For payday lenders, targeting the vulnerable is not an accident, it’s a business strategy,” Alvaro Bedoya, executive director of the Center on Privacy & Technology at Georgetown Law School, said when Google announced its policy. “Today, the world’s largest search engine is saying, ‘We want no part in this.’ ”

But the new rules were not as far-reaching as they initially seemed.

The loophole in Google’s policy was described by a person who kept notes from a conversation in which Google officials explained the ban. This source said that the tech giant acknowledged that its advertisers’ websites are allowed to feature loans that do not comply with Google’s policy — the advertisers just need to ensure that the high-cost loans are not mentioned on the webpage where the user first lands after clicking on the ad.

“The fact that you have noncompliant products on another page is not a problem,” the person said.

Google’s spokeswoman declined to respond on the record.

ACE Cash Express advertisements that ran on Google after the tech firm enacted its payday loan ad ban featured a link to an altered version of the company’s homepage.

This landing page did not mention payday loans, but it prominently stated: “Money when you need it most. ACE makes it fast and easy.” Users who clicked on “Learn More” were taken to another page where they could apply for payday loans, installment loans and auto title loans, all of which typically feature APRs well above 36%.

Unlike many other online payday lenders, ACE Cash Express is licensed to make loans in all of the states where its borrowers live. The privately held company, which also operates more than 950 stores in 23 states, did not respond to requests for comment.

Gaming the policy, or flouting it

Google says that its ban on high-cost loans applies not only to lenders but also to so-called lead generators. These are companies that collect a raft of personal and financial data from potential borrowers and then sell it to lenders.

Consumers who elect to provide sensitive data to online lead generators may be so desperate for cash that they do not see another choice. But it is a decision that many consumers will come to regret.

After a lender buys a particular lead, the borrower’s information typically remains available for sale, which creates opportunities for fake debt collection schemes, fraud and identity theft, according to the 2014 Pew report.

American Banker found advertisements on Google from lead generators that appeared to be trying to game the company’s 36% APR cap.

OnlyLoanz.com was one of the advertisers. When users clicked through to the company’s website, they landed on a page that had an APR disclosure section. “We are a lender search network, and the Representative APR is from 5.99% to 35.99% Max APR,” it stated.

But then came another disclosure that called into question the site’s adherence to Google’s policy. “Some lenders within our portal may provide an alternative APR based on your specific criteria,” the website stated.

OnlyLoanz.com did not respond to emails seeking comment for this article.

Other companies that advertised on Google appeared to be in even more straightforward violation of the company’s policy.

Mobiloans, an online lender that is owned by the Tunica-Biloxi Tribe of Louisiana, was among the top results from a Google search for “payday loan online.” When users clicked on the Mobiloans ad, they landed on a page that listed APRs between 206% and 425%.

Mobiloans did not respond to a request for comment.

LoanSolo.com, another lead generator that was recently advertising on Google, stated on its landing page that the company is unable to provide customers with an exact annual percentage rate, but that the APR on a short-term loan can range from 200% to 2,290%.

LoanSolo.com also could not be reached for comment. An email bounced back as undeliverable, and the company’s website listed an incorrect phone number.

Who’s to blame?

Google touts its payday loan ad ban as a success.

In the same blog post, Google said that it has beefed up the technology it uses to spot and disable noncompliant ads. The search giant declined to provide more information to American Banker about the steps it takes to ensure that advertisers follow its payday loan ad ban.

But David Rodnitzky, CEO of the ad agency 3Q Digital, said that Google uses both technology and a team of human reviewers to identify advertisers that violate its advertising policies.

Legitimate companies that are good customers of Google can sometimes work with the search giant to reach a compromise, Rodnitzky said. For example, these companies might be allowed to advertise on a different set of keywords than the advertiser originally selected.

“Google is never a company that you want to have on your bad side,” Rodnitzky said. “They have enough market-maker power that that’s not a company you want to run afoul of.”

Less reputable advertisers often play a cat-and-mouse game with Google, according to Rodnitzky. As an example, he said that an online payday lender might set up a Google ad campaign with $500 on a credit card.

The advertisements might run for a couple of weeks before Google blacklists the website, Rodnitzky said. Then the organizers might buy a new URL and use a different credit card to start the same process again.

One of the Google advertisers that American Banker identified over the summer was a lead generation site called DollarFinanceGroup.com. By early fall, the Hong Kong-based website was no longer operating, and an email sent to the address previously listed on the site was returned as undeliverable.

“It’s almost impossible to prevent small-scale fraudulent advertising all the time,” Rodnitzky said.