-

Credit quality is improving at Old Second Bancorp Inc., but the struggling company is still losing money.

October 27 -

Hit hard by defaults on construction loans, Old Second National Bank in Aurora, Ill., has agreed to an enforcement order with its regulator that requires it to boost a key capital ratio by the end of the third quarter.

May 18 -

Capitol Bancorp Ltd.'s credit costs are shrinking, but its capital hole is only getting deeper. The $2.5 billion-asset company, which has dual headquarters in Phoenix and Lansing, Mich., reported on Thursday a loss of $22.8 million for the third quarter, a 56% improvement from the loss it reported a year earlier.

November 11 -

Anchor BanCorp Wisconsin in Madison is once again hoping it can push back to the due date of its line of credit.

November 8

Old Second Bancorp's management team might believe the company has turned the corner, but industry observers are convinced the company remains stuck in a rut.

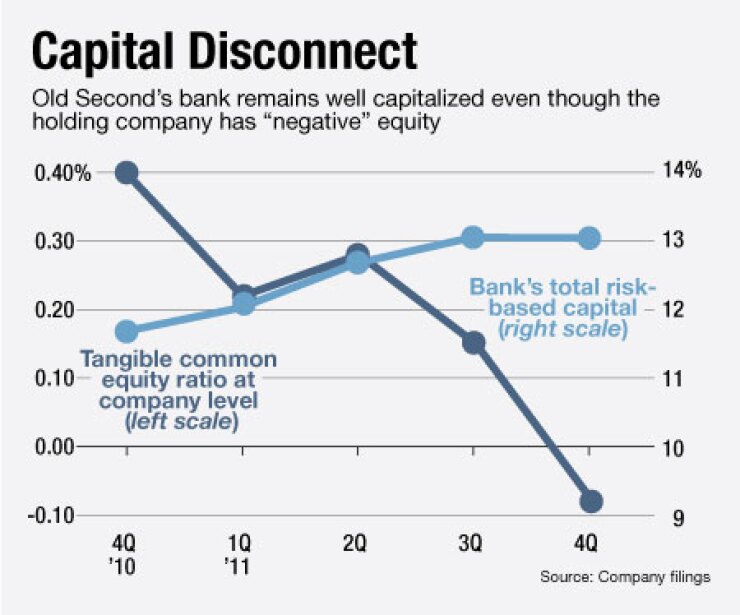

The $1.9 billion-asset company in Aurora, Ill., is among a group of struggling community banks that have stayed afloat despite particularly stubborn loan books. Old Second's bank ended 2011 with capital ratios above thresholds established by regulators, leaving it in better shape than many of its troubled brethren. Still, the company ran out of tangible common equity during the fourth quarter and has $232 million of nonperforming assets left to resolve.

"They feel like they are improving and they believe that as things get better, their prospects for raising capital at a better price will improve," says Brian Martin, an analyst at FIG Partners LLC. "The hole is just so big and there is this discrepancy between tangible common equity and reserves to nonperforming assets."

At this point, the company is likely holding out hope that no major problems arise and that it has taken aggressive enough marks to push its problems out, says Eliot Stark, a managing director at Headwaters MB, an investment bank in Denver.

"The best hope is that the economy continues to improve and nonperformers go down naturally or they are able to dispose of some of the properties at their current carrying value or maybe even higher. That's the best scenario," Stark says. "The worst -case scenario is that they continue to see more loans slide in the front door as others are moved out the other side."

Calls to Old Second were not returned. Executives said during a conference call late last month that sales of foreclosed properties in the last six months have priced between 87% and 112% of book value.

Bill Skoglund, Old Second's chairman and CEO, said he was upbeat about the company's recovery. "Despite the fact that we still have a lot of work to do and we are fighting a number of headwinds with the economy and other political issues, I continue to be cautiously optimistic that we have turned the corner on getting control of our problem loans," he said during the call.

Skoglund also said that the bank's capital is stable, which puts it in a position to grow. However, several analysts say the company will ultimately need to raise capital.

The company's capital consists of $100 million of trust-preferred securities and subordinated debt, and $73 million from the Treasury Department's Troubled Asset Relief Program. Like many companies, that money is levered and pushed down to the bank as equity. Having negative tangible common equity at the company level does not immediately put the bank in danger of failing.

Regulators demand bank holding companies serve as sources of strength to their units, but as long as the bank does not become critically undercapitalized, regulators typically let the banks work on their problems. There are several companies,

Negative equity, along with the amount of debt at the holding company, makes it hard to raise new capital and creates a logjam for purging bad assets. A company cannot aggressively work through problems without a more-robust capital position.

That logjam causes Michael Iannaccone, president of MDI Investments, a community bank advisor in Chicago, to think bank failures could tick up in 2012. While he would not discuss specific banks, he says regulators could get antsy with banks that are still dealing with large amounts of bad assets.

"All of these banks have consent orders that specifically tell them to get rid of nonperforming assets and we haven't seen it," Iannaccone says. "They gave them a pass for a year and nothing changed. The regulators could be forced to go back in and start writing down assets. If that happens, I strongly think we could have 100 to 150 failures this year."