-

Led by energy, and bolstered by a diversifying economy, the Texas metropolis is drawing a wave of new banks to vie with the city's incumbents.

September 14 -

Though it's the big banks that are working with energy companies, smaller institutions still expect huge opportunities, some risks aside, to serve ancillary businesses and consumers.

January 12

The North Dakota oil boom is almost giving community bankers more than they can handle.

The 2008 discovery that roughly 4 billion barrels of oil could be collected and recovered from the Bakken geological formation has led companies like Marathon Oil Corp. and Whiting Petroleum Corp. to pour into the western part of the state.

The oil rush has brought hundreds, if not thousands, of workers, all needing places to live and to keep their money. The boom has also led to newfound wealth, as some landowners make a mint from leasing mineral rights to their property.

Smaller banks dominate the financial landscape in western North Dakota, and the surging oil and natural gas activity has helped most of them grow. Assets at First National Bank & Trust Co. of Williston rose 16% from a year earlier, to $320.8 million at Sept. 30. At Lakeside Bank Holding Co. in New Town, assets rose 24% from a year earlier, to $304.9 million.

The growth hasn't harmed banks' credit quality. At Lakeside, noncurrent assets totaled 0.22% of all assets at Sept. 30, compared to 0.5% a year earlier.

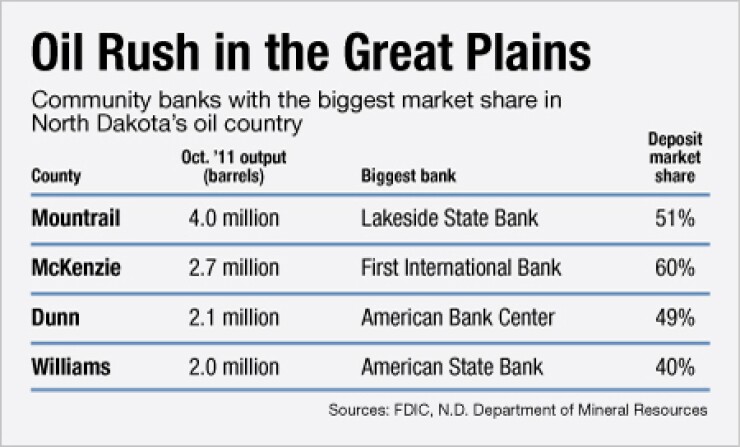

In the four North Dakota counties that have the most oil production — Dunn, McKenzie, Mountrail and Williams — community banks are the only players. Those banks range in size from the $74 million-asset Union Holding Co. in Halliday to the $1.1 billion-asset Watford City Bancshares Inc.

There is so much liquidity that a number of banks have stopped accepting deposits, says Robert Sorenson, president and CEO of First National Bank & Trust. While the bank stopped issuing certificates of deposit to non-customers, other banks are refusing to accept deposits from anyone, he says.

Community banks are already having a hard time finding ways to optimally redeploy incoming deposits, and things are unlikely to slow down next year. "It's like when the tub starts to fill up and then it overflows," Sorenson says. "We're just trying to control the growth."

North Dakota was among the most economically sound states before the oil boom hit. Unemployment in the state was 3.5% in October, according to the most recent data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. It has been more than a decadesince a bank failed there.

Now it's almost an embarrassment of riches for the state, with a population of just 673,000. (Only Vermont and Wyoming have fewer people.)

Homebuilders are busily constructing homes in North Dakota, but they can't keep up with demand from newcomers tied to the energy trade, says Gary Petersen, Lakeside's chairman and chief executive. "We hear about a new project, it seems like every other day," he says.

Staffing is a new problem for banks in North Dakota, not only because there aren't enough people to fill the openings, but also because housing has gotten expensive, Petersen says.

The residential rental market in Williston, located at the center of the state's oil industry, has hit prices resembling New York or Hong Kong. Monthly rent on a three-bedroom apartment in Williston can range from $2,500 to $3,000.

"We've had elderly people leave town because they can't afford to live here anymore," Sorenson says.

A population surge also translates into growth in a number of products and services offered by banks. Commercial lending is booming for oil suppliers, says Brent Mattson, the president of the Minot location of Bremer Bank, which is owned by the Otto Bremer Foundation, an $8 billion-asset holding company based in St. Paul, Minn.

Mattson says he has seen a spike in demand for wealth management and trust services, as landowners come into new wealth after leasing mineral rights to oil companies.

"We're seeing much broader demand on the commercial lending side," Petersen says. "Smaller service companies, like earth movers, construction firms, fuel suppliers, have grown and demand is much higher than it used to be."

Oil-drilling companies that move into state such as North Dakota often bring their own financing, and so they usually do not need loans from local community banks, Petersen says.

"We like to finance people who have their headquarters here or already have their banking relationships here," Mattson adds.

Community banks aren't the only beneficiaries from oil exploration.

Wells Fargo & Co. in San Francisco, is North Dakota's biggest bank even though the company is absent in the state's most oil-rich counties. The company has also increased its lending to trucking companies, apartment developers and other companies reliant on the oil industry, says John Giese, a regional business banking manager based in Bismarck.

Like any other market experiencing a sudden economic boom, there is always an underlying fear of having the rug "pulled out from under us," Sorenson says. Risks include a sharp drop in oil prices, or new regulation that would limit hydraulic fracturing, the extraction method used in North Dakota.

"You've got to be careful that you don't do too many apartments and hotels," Mattson says. "We're trying to diversify our portfolio. You need a nice, even mix."