-

M&T and Comerica defended the deal-related charges that hurt their third-quarter earnings, saying future fees and new business will make the costs a distant memory. PNC says its deals will pay off quickly, too.

October 19 -

Two years after reaching a deal for Wachovia's crisis-time acquisition, Wells Fargo is only now beginning to integrate Wachovia's core markets.

October 15

M&T Bank Corp. took the good with the bad when it bought Wilmington Trust Corp.

To get a top-flight trust operation, the Buffalo, N.Y., bank had to accept with it a damaged brick-and-mortar lender in Delaware.

M&T — among the speediest integrators in bank M&A — has been slow to integrate both units. The $78 billion-asset company is scheduled to finish converting Wilmington Trust's wealth and corporate systems in June,

It is a far different story than its purchase in 2009 of Provident Bankshares Corp. It closed the deal for the Baltimore bank on a Friday and

Why has M&T been so slow bringing it into the fold?

The same reason a blue-collar guy waits to dig in to the first course at a black-tie dinner: he wants to make sure he uses the right fork.

"The Wilmington Trust customer base and the bank itself were set up differently than the other banks we have come across. It was more customized, more specialized," says Mark J. Czarnecki, M&T's president.

"We have a model down on traditional bank acquisitions — that model would have us go faster," he says. "Here, we're taking it a little slow."

Wilmington Trust is M&T's first foray into upper-crust banking. It sets up tax shelters for millionaires. M&T banks the other 99%. M&T has bought 23 banks since the early 1970s, most of them simple operations. It knows that rushing into an unfamiliar business leads to trouble. M&T booked a $79 million charge last quarter tied to a stake in a Miami commercial mortgage firm it acquired just before the crash.

M&T wants to avoid a clumsy, brand-diluting takeover of an elite bank, which Wilmington Trust was despite its loan troubles, executives say.

There are a lot of moving parts. Wilmington Trust had two U.S.-chartered banks and more than a half-dozen investment businesses that handle corporate and personal trust work in 90 countries.

Wilmington Trust was forced to sell itself when bad loans to homebuilders sent customers fleeing from its marquee trust division. M&T did not want to further rattle Wilmington Trust's customers and advisors, so it kept the Wilmington Trust name — something it had not done in previous acquisitions.

"Their whole natural advantage, their business strategy, was around being from Delaware, that was the centerpiece of who they were," Czarnecki says. "To rename them M&T would be to take away their identity in a way that would not be helpful — we thought about that a lot."

Going slow helped end the customer and employee attrition, Czarnecki says. The post-merger growth in checking accounts in Delaware is the best M&T has ever seen. But being patient has translated to higher costs.

M&T investors scoffed when the normally disciplined company's expenses soared last year on $84 million in merger charges. The deal has delivered scant cost savings and revenue gains to date, though M&T is projecting hefty amounts of each. It intends to remove $80 million of Wilmington Trust's annual operating costs, with the bulk of those savings projected for the second half of this year.

M&T's trust revenue exceeds pre-merger levels but was flat during the last six months. M&T blames the volatile economy's toll on corporate and wealth advisory services. Investors worry it has not been able to win back clients.

M&T — which counts Warren Buffet as a major investor — is not an outfit that seeks quick returns, executives stress. Wilmington Trust will pay off over the long haul, they say.

"It will take some time," says Rene Jones, M&T's chief financial officer. "We're pretty patient. We're already seeing new customers being generated."

Analysts are giving M&T the benefit of the doubt because of its record of making deals work.

"The addition of [Wilmington Trust] provides a meaningful source of earnings leverage for [M&T], particularly as we began to look forward to" the second half of 2012, Sterne Agee & Leach analyst Todd Hagerman wrote in a note to clients in January.

TRADING PLACES

Wilmington Trust and M&T are from different worlds.

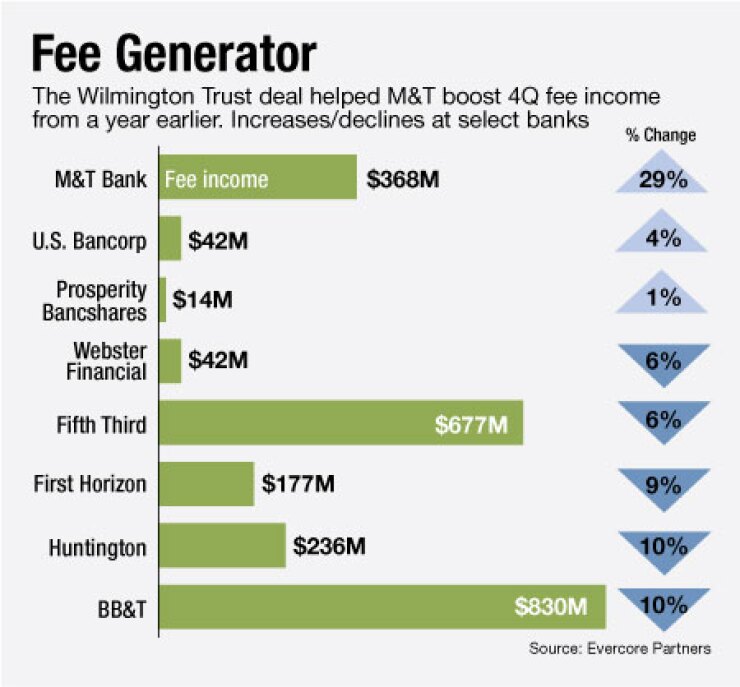

M&T makes money from interest on loans and securities. Wilmington Trust makes it from fees. Those fees — mostly from handling cash for rich people and big corporations — are the main reason the risk-averse M&T is making its up-market gamble. About 37% of M&T's revenue is now fee-based, up from about 33% before the deal.

"The traditional fee opportunities in banking are being restricted, if you can build another source of fee revenue — that is the obvious strategic play," Czarnecki says.

The franchises have other differences. Wilmington Trust was crippled by bad loans it made to Delaware homebuilders. M&T is renowned for superior underwriting. Its expertise in construction lending in particular was a key reason it pounced swiftly on Wilmington Trust in late 2010.

The du Pont family started Wilmington Trust 100 years ago to manage its fortune. Today it helps people with at least $10 million of liquid assets figure out which heir gets the beach house and which gets the boat. It oversees the interests of investors that lent money to corporate giants that went bust, such as General Motors and Lehman Brothers. It handles trustee, retirement, investment and cash management and other services for multinational companies from Switzerland to the Caribbean.

A couple of hardscrabble Buffalo businessmen looking to make equipment loans to local manufacturers founded M&T in the 1850s. Business lending is still its primary business; it extends credit to health care operators, hotels and New York apartment building owners. M&T had a trust and brokerage arm before buying Wilmington Trust, but it was in a different league, selling mutual funds, annuities and college savings plans to everyday folks at branches from Maryland to New York. It also sets up trusts to manage bonds sold by cities and towns.

TWO-PRONGED ATTACK

The integration of the $11 billion-Wilmington Trust has two parts: Wilmington Trust Co., Delaware's top commercial bank, and Wilmington Trust FSB, an umbrella for Wilmington's retirement, institutional and employee benefit services operations.

M&T waited more than three months to convert Wilmington Trust's commercial bank, which had 48 branches in Delaware. It took extra time because Wilmington Trust's retail operations had novel back-office system to handle the complex finances of its wealthy clients.

M&T has a standard banking system that assumes customers generally buy the same kinds of home loans or checking accounts. It had to tweak its system to account for the customized services demanded by Wilmington Trust clients, some of whom count on the bank to manage tens of millions of dollars.

The integration of Wilmington Trust's wealth and corporate services is sort of a reverse-merger within the merger. M&T is folding its trust and brokerage arms into the Delaware bank's much larger and more complex trust operations.

Wilmington Trust managed $42 billion of assets at the time of its sale; M&T's trust operations managed about $13 billion. The Wilmington Trust savings bank converted to a national bank, and merged with one of M&T's two U.S. chartered banks.

Two steps remain in the integration of the trust operations. In March, the M&T-branded mutual funds are slated to become Wilmington Trust funds. In June, Wilmington Trust converts to the same trust accounting system M&T uses. Wilmington Trust had been prepping to convert to a similar model employed by M&T before the takeover, so M&T stuck with that prior schedule.

Long term, M&T's aim is to refer the aging business owners it has banked for years to Wilmington Trust as they retire and cash out.

"This is a very high-end product," Czarnecki says. "The money will be made in this transaction for us over longer periods of time by introducing that high-end service to our customer base."