WASHINGTON — It will soon become even harder to tell the difference between a federal thrift and a national bank.

The thrift charter has already been endangered for years. What once were 4,000 mortgage-focused lenders has dwindled to just over 300, and Congress already did away with a dedicated regulator for federal thrifts following the crisis.

But as the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency implements a provision of the recent regulatory relief law, allowing most thrifts to "elect" to be treated as national banks rather than go through a more cumbersome charter conversion process, any meaningful difference between the two charters will be close to negligible.

“There is really no reason to hang onto the federal savings association charter unless you’re principally a mortgage lender,” said Alessandro DiNello, president and CEO of Flagstar Bancorp in Troy, Mich.

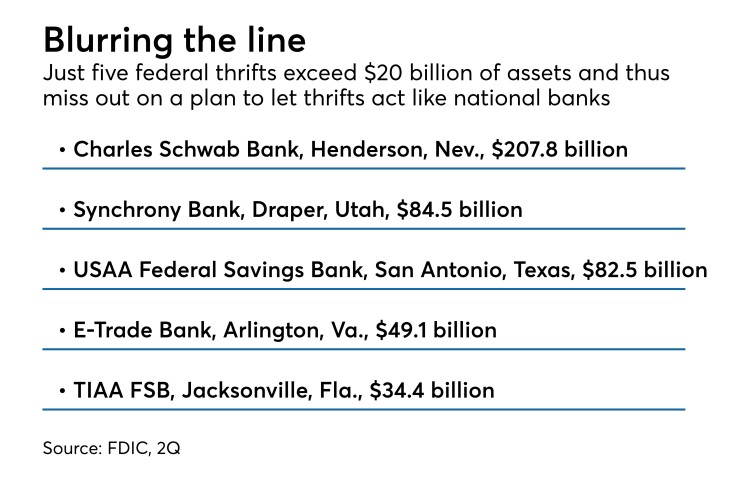

Under the new law and a proposed OCC rule, thrifts with less than $20 billion in assets could keep their charter but could opt for a new designation freeing them from limits on commercial lending imposed on savings and loans. They would also be exempt from meeting the "qualified thrift lender" test — requiring that at least 65% of a lender's portfolio be made up of mortgage- and housing-related assets.

All but five of the 320 OCC-regulated thrifts fall below the $20 billion threshold, including Flagstar. Some have pushed for such a change for years, arguing that the limits of the federal savings association charter are risky when loan diversification is seen as a safer bet to protect against downturns.

DiNello said Flagstar, which had about $18 billion of assets as of June 30, is considering electing to be treated as a national bank once the rule is finalized.

He said the thrift charter was previously seen as an easier way to branch nationally, but that became less meaningful when the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act also allowed national and state-chartered banks to more easily branch across the U.S.

“We’ve been moving toward more of a commercial banking platform, so having this option is a relief and is very important to us,” he said.

For the past several years, the OCC has pushed Congress to offer more lending flexibility for thrifts.

"A lot of thrifts were converting to state commercial banks to get out from under the QTL test,” said former Comptroller of the Currency Thomas Curry, now a partner at Nutter McClennen & Fish.

This proposed election will help thrifts “avoid paying legal fees to change their charter” and “allows flexibility for them to stay as a thrift but enjoy national bank powers,” said Curry. He noted that the OCC had already started examining thrifts the same way as national banks when he ran the agency.

Both the OCC and representatives of thrifts say the full charter conversion process is time-consuming and more costly than simply electing for a change in the business plan to make more commercial loans.

The OCC’s proposed election appears “easy to do and the downside is so minimal that I think a good number of them will apply,” said Eric Luse, co-founder of Luse Gorman. “And this is not an expensive process.”

However, some observers argue that the new election is more complicated than initial perceptions since thrifts now enjoy certain benefits over commercial banks that they would have to relinquish. For example, federal thrifts, unlike national banks, are authorized to invest in service corporations.

“Almost any federal savings association can elect this option" to operate as a national bank "but it has trade-offs, such as service corporation investment powers they have to give up,” said Douglas Faucette, a partner in Locke Lord's corporate department and chair of the bank regulatory and transactional practice group. “Effectively, it really creates a whole new charter category supervised by the OCC. So now there are OCC-regulated federal savings associations with no national bank treatment and federal savings associations with national bank rights.”

Because of some of the rights that thrifts will have to give up, Faucette said, thrifts may not rush to be treated as national banks.

“This is complicated; one size doesn’t fit all and it’s going to take some time before it settles in,” he said. “I don’t think it’s a bad thing, but it’s just more complicated than at first blush.”

The OCC’s proposal is also not the death knell for thrifts. There are still roughly 40 other state-chartered thrifts that cannot elect to be treated as national banks, according to Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. data.

Still, the prospect of more thrifts having a smoother path to becoming like national banks continues a trend of the thrift charter losing its footprint in the industry and its applicability.

That evolution started arguably with the failure of over 1,000 thrifts during the savings and loan crisis of the '80s and '90s. Then, after some of the largest thrifts also collapsed in the 2008 mortgage debacle, Congress merged the Office of Thrift Supervision into the OCC with passage of the Dodd-Frank Act.

“The entire infrastructure to support the thrift industry is gone. Their own deposit insurance and regulator is gone,” Faucette said. “I don’t see the thrift industry as benefiting from any special status, and the attempt to encourage them to wet their feet in commercial lending is a clear example of that.”

Though the OCC’s proposal further blurs the lines between a thrift and national bank charter, DiNello said the move is appropriate considering the changes in banking and to create a more even playing field.

“The whole idea is to give those that have the thrift charter more flexibility in the assets they put on their books,” he said. “And it’s been recognized that over time, thrifts have become more banklike.”