Regional banks are finding that profitable growth is nearly impossible in their traditional businesses. Consequently, many are taking the untraditional approach of diversifying in areas dominated by equally beleaguered rivals.

In all of these instances, the banks undertook these counterintuitive moves in response to weakness in their core businesses, according to a Moody's analysis of strategic moves by regional banks. And while each of the new ventures deserves to be evaluated on its own, the ratings agency says, they carry significant risk of making a bad situation worse.

Ventures into other banks' traditional turf "are going to inevitably push down pricing," says Allen Tischler, a Moody's senior vice president. "Certainly there are many instances in the history of banking where banks move into the same area all at once. Residential construction lending is one, and a lot banks got burned."

BB&T Corp. has a new focus on energy. People's United Financial Inc. is going beyond its Northeastern home to provide asset-based lending down the Eastern Seaboard. Regions Financial Corp. is back in auto lending after exiting the space several years ago. Capital One Financial Corp. is betting on store-branded credit cards. And Hudson Valley Holding Corp. is bulking up on multifamily.

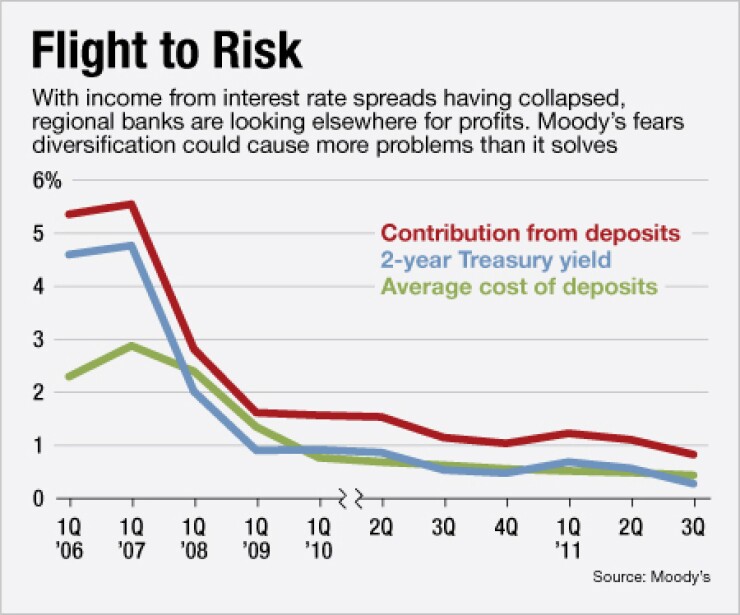

By Moody's analysis, banks wouldn't be venturing so far afield if they were getting the earnings they need at home. An extended period of near-zero interest rates has collapsed spread income, and limits on the ability to wring fees from checking have added to the stress. With retail accounts stripped of most of their earnings potential — the risk-free spread between the average cost of deposits and two-year treasuries fell to nothing today from 2.3 percentage points in 2006 — the simplest and safest form of bank income has shriveled up.

"There is pressure that these changes are long-lived, and therefore, the banks have to respond," says Curt Beaudouin, a senior analyst at Moody's.

The strain of the current environment can lure banks into fields in which they have no natural advantage, says John Pancari, an Evercore banking analyst. "It's not just the function of seeking asset growth," Pancari says of business-line expansion plans. "It's that core commercial loan demand is weak, and banks have a significant amount of excess deposits on their balance sheets."

While overreach is a historically easy trap to fall into, Pancari says, underwriting is generally still tight and regulators unusually wary. The industry's current aversion to brokered loans will also likely help keep standards high.

The banks themselves insist that their business expansions aren't a stretch because they're natural offshoots of current business lines. Huntington Bancshares Inc., which operates in six Midwestern states, is making an auto finance push outside its geographic boundaries. But Nick Stanutz, director of Huntington's auto finance group, can list half a dozen reasons why the bank considers this a solid strategy.

Huntington has built up tremendous good will by standing by the U.S. auto industry when it flirted with collapse. The bank moves into territories only when a major player has exited and it can acquire portions of their team (Sovereign in Pennsylvania, for example, and M&T in the upper Midwest, which was bought out by Bank of Montreal.)

Huntington's auto finance staff works locally, unlike its competitors' staff. And the bank does not compete on price, garnering what Stanutz says is between 25 and 50 basis points more of interest than its competitors on the average loan.

"If the dealer's interested in price, he's going to have a lot more choices than a year ago," he says. But Huntington doesn't have to offer rock-bottom pricing to attract dealers' attention, Stanutz says, likening the dealer's franchise to a high-end retailer.

"There's the Wal-Mart dealer, the Macy's dealer and the Nordstrom's dealer," he says. "We focus on the latter two."

With renewed interest in the auto finance market someone's likely to get hurt, Stanutz says. It just won't be Huntington, he says.

"I hate to have more competition, but at the end of the day, hardly anyone has a model like us where we'll set up shop in a marketplace," he says.

Regions is another bank that's stepped into the auto finance space — a line of business that it abandoned several years ago. While the company expects to have 1,200 dealers signed up by the end of this year, it says it is not just piling into a relatively strong sector. The bank sees lending to car dealers as a way to diversify in markets where it already holds a dominant position. (See story on page 12.)

Its work with auto dealers is an area "we have experience in and [which] supports our efforts to meet the needs of more customers in the communities we serve while also diversifying our loan portfolio and revenue streams," a Regions spokeswoman said in an email. "We continue to experience steady growth in the business, with loan growth of 4%" from the previous quarter.

Moody's, however, remains generally skeptical of expansion in the current environment. "If you look at some of our highest-rated banks, they're not banks that emphasize above-average growth," Tischler says. "Even those banks would be pressured if other institutions tried to compete on their home turf, but it's obviously easier to defend a space where you have expertise and market position."

Pancari has similar concerns, though he says there's an opening for banks that have proven infrastructure. BB&T, for example, went into energy lending this year — but only with the help of former energy lending staff from Sterling Bank, who left after their company was acquired by Comerica. "I feel better about it when they acquire an entire team," he says.

And so long as industry players maintain pricing discipline, there's not much to lose. "Spreads are still favorable, even though it's getting more competitive," Pancari says. "Also their funding costs are still low."