-

The dismantling of state agencies that funded affordable housing had upended nonprofit development in California.

March 24 -

A movement to jump-start affordable-housing development is gathering momentum in New York and elsewhere, and bankers are concerned that new mandates would cut into their profits on loans for such projects.

March 13

New York banks have been worried since Bill de Blasio was elected mayor in November that he might aim a wrecking ball at the booming business of multifamily lending.

They are thinking sunnier thoughts now. First, De Blasio announced in May that he will let apartment developers construct taller, larger buildings in exchange for a requirement they include more affordable housing units, as part of his plan to create or preserve 200,000 affordable units over 10 years. Overall, many lenders think that could promote big development and more profitable loans.

Most recently, a city regulatory board cast a critical vote at the end of June. The New York City Rent Guidelines Board approved a 1% rent increase for one-year apartment leases. While that's less than what bankers wanted to protect the economic interests of existing landlords (their borrowers), it's better than De Blasio's call for a rent freeze.

The details are specific to New York, but the situation highlights the political risks facing lenders in any large U.S. city with big apartment buildings and demand for more.

Recent policy changes in California, for example,

Rent-regulated multifamily lending, while growing and lucrative, is always going to be susceptible to the vagaries of politics, says Joseph Ficalora, president and chief executive of the $44 billion-asset New York Community Bancorp (NYCB).

Any city can adopt well-intentioned policies that promote affordable housingbut hurt the private investment required to make the housing available, Ficalora says. Elected leaders need to be mindful not to overreach, he says.

It's unlikely that De Blasio "will take a step to jeopardize rent-regulated housing," Ficalora says.

He recalled a cautionary tale from decades ago, when a city tax change seriously damaged the rental housing market. "The last time [politics got in the way] there was a negative effect on the market by an unthinking government.... They won't do that again."

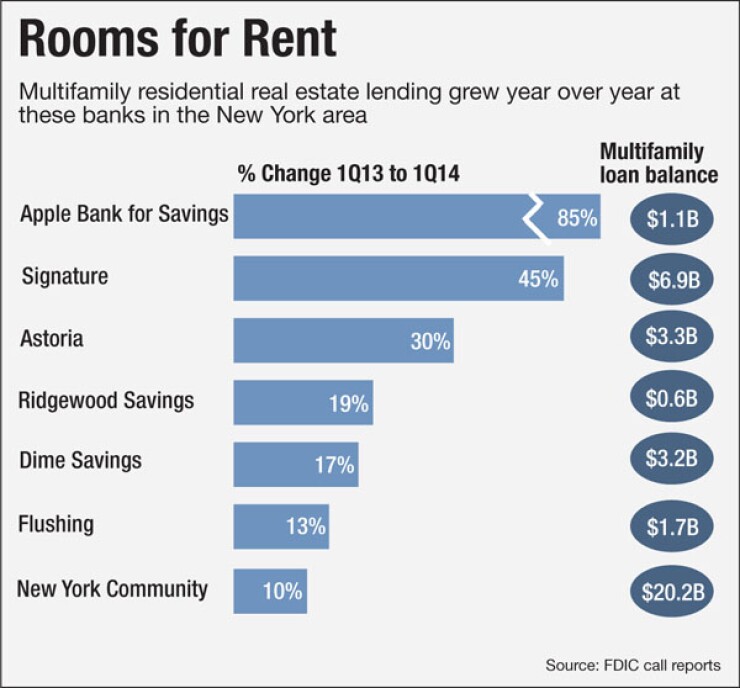

New York-area banks have a lot at stake. Banks that conduct the bulk of their business in the city's five boroughs, Long Island and Westchester County, N.Y., have seen a huge increase in multifamily lending in the past year.

The multifamily loan book at $11.6 billion-asset Apple Bank for Savings grew by 85% to $1.1 billion at the end of the first quarter, from a year earlier. The $23.1 billion-asset Signature Bank (SBNY)'s multifamily loans grew 45% to $6.9 billion during the same period.

Even New York Community, the longstanding king of the multifamily mountain, has seen double-digit growth. Its multifamily loan book rose 10% to $20.2 billion during the same period.

It's gotten to the point that some New York-area banks see multifamily lending as mandatory. Signature, which was founded in 2001, initially took deposits from real estate management companies, but did not lend to that industry sector, Eric Howell, executive vice president of corporate and business development, said at a Morgan Stanley financial services conference on June 11.

"But they said, 'Hey, we'll give you the deposits, but you need to lend to us as well,' " Howell said. "We recognized that being a bank in New York City, how do you not make multifamily loans?"

De Blasio's election appeared to throw a wrench in the multifamily lending machine. Some had

But the mayor's affordable housing initiative may actually be good for New York Community, as it could potentially increase its lending base, Ficalora says.

"I have no concern about adding new affordable housing," Ficalora says. "We should be fine with [those] changes. It helps make the market that we lend in larger."

De Blasio's promise of a rent freeze was seen as an even-larger threat to apartment developers and their bankers. Matthew Kelley, an analyst at Sterne Agee, noted that the city-approved rate increases for one-year apartment leases had never fallen below 2%.

"Given that operating expenses on properties are growing 4% to 6% annually, a rent increase of less than 2% would be painful for property cash flow," Kelley wrote in a May 23 research note.

While the Rent Guidelines Board's approval of a 1% increase is less than desired, a total rent freeze would have sent shock waves through the market, Ficalora says.

"If he would have changed the rules so there would be no rational investor who would take on responsibility for rent-regulated housing, that would have caused a serious deterioration in value," he says.

De Blasio may want to increase the number of affordable units in the city, but he's going to be careful not to rock the boat too much, says John Kanas, the chairman and CEO of BankUnited (BKU), a $15.6 billion-asset bank with five offices in New York City.

"Everyone's got an opinion about the mayor, and some are concerned," Kanas says. "My view is that the mayor is a very smart guy, and he understands that his administration will be judged on many things, one of which is the overall health of the New York economy. We believe he will make wise choices over time."