WASHINGTON — For nearly 10 years, the top officials at the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. warned about the danger of the declining level of federal reserves, but a funny thing happened when the Deposit Insurance Fund finally went broke in 2009: Nobody cared.

An event that once would have caused jaws to drop and cable commentators to panic was barely a blip on the radar.

The FDIC did not charge banks exorbitant fees to try and rebuild the fund or even employ its backup plan — borrowing money from the Treasury Department.

Instead, it required banks to prepay future premiums to help it ensure it had enough resources to continue to manage proliferating bank failures.

But the move raised an intriguing question: Does the Deposit Insurance Fund matter anymore?

With the fund $8 billion in the red as of Sept. 30, and the ratio of reserves to insured deposits at minus-0.16%, it appears that the answer to the question is "no" — at least for now.

"Some of us have said: 'You don't actually really need a deposit insurance fund,' " said Edward Kane, a Boston College professor and fellow at the FDIC's Center for Financial Research.

But some argue that, once the crisis subsides and the pace of failures, which at 140 so far this year is nearly six times last year's volume, returns to normal, the fund may matter again.

"Almost everyone at least would agree that we ought to have a positive reserve balance at the FDIC," said Douglas Elliott, a fellow at the Brookings Institution.

"People are more relaxed about this simply because they see this as an extraordinary event but also believe that there's enough assessment power at the FDIC that it will basically earn its way back through premiums on the banks over" the long term.

However, he said, "that's not the best way to run a railroad."

Elliott drew a parallel to consumer checking accounts.

"Ideally, you keep a significant amount in your checking account. … If you have the overdraft capability, then you do have room to go considerably negative, as long as you think there are going to be ways to bring it back to positive," he said. "But the better public policy is to try to keep that balance positive."

Some observers argue that the fund is a bellwether for banks' health.

Because everyone is aware the banking industry is in tough times, there was no panic when the fund went negative, they said; however, it will be important to restore the fund to its ordinary 1.25% ratio of reserves to insured deposits over time to prove the industry is back to normal.

"The 1.25% is important because it provides a sense of how big the problems are that can be handled without abnormal taxing of the banks by the FDIC during a normal period of time, and without overreacting and putting so much money away that you really deny the economy the capital to grow," said Don Oglivie, the independent chairman of the Deloitte Center for Banking Solutions and the former head of the American Bankers Association.

"That's why that number is critical."

But others argue that the secret is out and there is little point in focusing on the DIF anymore.

The fund's solvency is a "technical artifact of accounting, and" it will be restored "eventually," said William Longbrake, a former chief financial officer at the FDIC and now an executive in residence at the University of Maryland's Robert H. Smith School of Business.

"What's really important, and I think the FDIC has communicated this quite effectively, is [that] they have enough cash on hand to not delay failures but to resolve them on a timely basis. As long as they have cash, the fund can be deeply insolvent, and it really doesn't matter. I think that explains to a large extent why you haven't seen much public reaction, certainly not from the banking industry."

In 2010, the DIF is likely to decline further. Experts widely predict the volume of bank failures to remain at 2009 levels, and the FDIC has set aside $38.9 billion to provide for future collapses, including $21.7 billion in the third quarter alone or nearly twice as much as it set aside in the second quarter. In September, the FDIC projected that the DIF could face total failure costs of $100 billion through 2013.

The agency is not projected to return the DIF ratio to 1.15% — its statutory minimum — until 2017.

Longbrake said it may take even longer.

"The huge assumption is that they can actually return the designated reserve ratio back to the 1.15 mark by 2017," he said. "That presumes that their estimates of future losses likely to be incurred through the resolution process are on the mark. I think there's a reasonably good chance that somewhere in the next year or so that we will revisit whether [it] is enough."

Some observers said the importance of the DIF will continue to decline.

A negative DIF is not "a big deal," in part because the public is aware that the government stands behind the agency, said Kane.

"It gives a degree of comfort to" the FDIC "and perhaps to some depositors to know that there is a fund," he said. "But there is an asset that isn't booked, which is the value of the government support. … As an enterprise, it's never going to be economically insolvent."

While they differ on whether the DIF matters, most observers agree the FDIC handled the situation in a creative way that avoided the downsides of the traditional choices available to it.

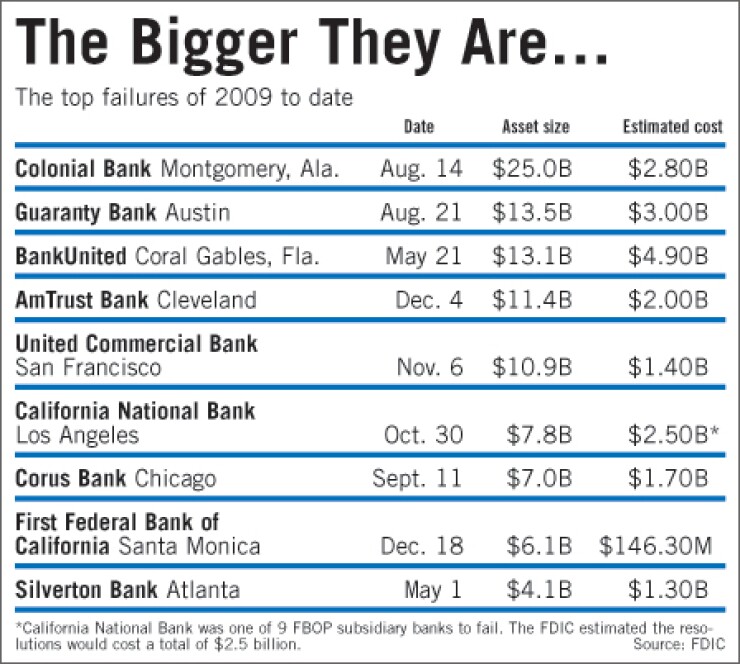

The steady stream of failures that began in the fourth quarter of 2008 continued into this year, averaging nearly three a week (the agency handled as many as nine in one weekend). The 140 collapses as of Dec. 18 was the fifth-most in one year since 1980.

Though the protection of depositors and transfer of failed-bank operations has gone smoothly, the agency's resources are being stretched thin. It boosted its 2009 budget for receiverships by over 500%, to $1 billion, and has proposed another giant increase for next year, to $2.5 billion. The agency has also proposed nearly doubling its temporary staff, to 3,400 people. In May, the agency announced plans to open a temporary satellite office in Jacksonville, Fla., to handle failures in the region after a similar move last year to open an office in Irvine, Calif.

By the end of the first quarter, the DIF's ratio of reserves to insured deposits had already plummeted to 0.27% — far below the legal baseline of 1.15% — and the agency had proposed a hotly contested fee of 20 cents per $100 of deposits on top of banks' normal premiums to stop the bleeding.

After bankers and lawmakers protested, the agency revised the plan in May, saying it would instead charge 5 cents per $100 of a bank's assets, beginning June 30. The somewhat lighter charge was made possible by a legislative push to expand the agency's authority to borrow from the Treasury.

The shift to basing the assessment on assets, instead of deposits, pleased community banks but angered several large banks. The FDIC had concluded that the new method made sense because large banks had been the beneficiaries of the Troubled Asset Relief Program and other government aid.

Still, the fund's balance kept shrinking — the reserve ratio was 0.22% at midyear — and banks assumed another special assessment was inevitable.

Despite the steady failures, the FDIC appeared to shift its focus away from a quick remedy for the DIF.

As lawmakers sounded alarms, arguing that higher FDIC fees would prevent banks from lending in their communities, agency officials indicated they were considering other options, including a Treasury loan.

Though the agency may legally borrow as much as $100 billion from the Treasury, FDIC Chairman Sheila Bair was clearly reluctant to tap this line of credit. Doing so could have created the perception the FDIC was getting a government bailout and hurt the agency's credibility among consumers.

As a result, the FDIC started trying to shift attention away from the DIF, including emphasizing the billions in its loss reserves.

Under accounting rules instituted during the savings and loan crisis, the agency must withdraw money from the fund that it expects to lose in the near future. In most cases, a failure will be paid for with these funds, unless the collapse is unexpected or more expensive than initially projected.

The fund balance — a representation of the agency's net worth — for years had been the most visible measurement of its resources, a mathematical trigger to determine a year's premiums and the basis for drawn-out debates over the level of funding banks should provide the FDIC.

But with the DIF depleted, the agency highlighted its liquid resources. For example, at the end of the second quarter, the DIF had just $10 billion in it. But total resources, including cash on hand in the loss reserves, were $42 billion.

Agency officials said it was important early on to be clear about the ramifications of the fund's going negative. Press briefings began to emphasize the importance of the loss reserves more than in the past, and officials stressed that insured depositors would notice no change after the DIF deficit.

"We didn't go negative without a plan," said Diane Ellis, a deputy director in the division of insurance and research.

Ellis added that, though the negative balance has proven to be a "nonevent for depositors," it still maintains importance in representing to banks how much they have to pay in assessments.

The fund is "really an indicator of how much and when the industry was going to pay for the losses," she said. "But it really is kind of meaningless to depositors because the FDIC certainly has enough resources.

"I would think it would matter just as much to the industry as it did before," she said.

If anything, the downward spiral for the DIF indicates the agency may need to charge more in good times than it has in past booms to prevent the fund from becoming insolvent again, she said.

"It has made us question more: What is the appropriate target size to build up the fund in good times. This would seem to be clear evidence that 1.25% is not enough and that perhaps we should be revisiting what the appropriate target is for good times."

In September, the agency unveiled a new solution that avoided both a new premium and borrowing from the Treasury. Banks and thrifts would essentially give the agency a $45 billion loan in the form of a prepayment of three years' worth of premiums. The cash would give the FDIC more liquidity to deal with current failures, but the fund would be built up slowly. (Officials predicted that the fund will be solvent again in 2012.)

The solution was seen as a win-win. The FDIC gets the money, and banks can report the prepayment as a depreciating asset. Gradually, the agency will book income to the fund for the amount of the prepayment that each bank is assessed quarterly under its normal risk-based pricing schedule. The bank will report that amount as an expense. Actual premium amounts can be adjusted if the agency finds the prepayment overestimated or underestimated its funding needs.

Agency officials also emphasized that they had raised $45 billion from the industry in an effort to ensure the public saw the FDIC as well-positioned to deal with more failures.

The prepayment, in combination with the emphasis on the loss reserve and the higher Treasury credit limit, "made it look like the fund was in good shape and the FDIC was strong enough to withstand any kind of continued deterioration in bank assets," said Ogilvie. "I think that explains partly why there wasn't as much concern as you might think."