A new diversity rule for companies listed on the Nasdaq stock exchange represents the latest push to convince banks to add more women and minorities to their boards of directors.

While the standards are facing some pushback, their recent approval by the Securities and Exchange Commission puts pressure on Nasdaq-listed banks to rethink long-standing approaches to recruiting board members, if they have not already done so amid insistence from investors and state officials.

Advocates for greater board diversity argue that directors exercise influence over a bank’s culture and strategic direction, and say that diverse leadership is often linked to

“Leadership and senior management should reflect the communities that they serve in order to create more inclusive decision making and to ensure equitable access,” said Rawan Elhalaby, senior economic equity program manager at the Greenlining Institute.

The Nasdaq rule requires companies traded on the exchange, a group that includes more than 300 banks, to disclose the diversity of their boards of directors each year. And by giving firms the option either to appoint at least two diverse directors or explain why they are not meeting that threshold, the rule is intended to gradually make boards more diverse.

Two of the nation’s largest states have made related moves in recent years. In 2020, California

And last month, the New York State Department of Financial Services

Critics of the Nasdaq rule argue that it imposes illegal quotas and poses an undue challenge for certain companies. They also point to industry-led efforts that are already under way.

In recent years, certain banks

If it makes sense for a company to diversify its board, then a government mandate should not be necessary, said Paul Kamenar, general counsel of the National Legal and Policy Center, a right-leaning nonprofit organization that monitors public officials.

The group, which filed a comment letter opposing Nasdaq’s board diversity rule, is now considering legal action. It argues that the rule violates the Constitution by imposing arbitrary racial and gender quotas.

Kamenar criticized as “disingenuous” the provision of the Nasdaq rule that requires companies to provide an explanation if they do not have at least two diverse members.

Sen. Pat Toomey of Pennsylvania, the top Republican on the Senate Banking Committee, also slammed the SEC for approving the rule, saying in a press release this month that SEC Chairman Gary Gensler is “turning a financial regulator into a laboratory for progressive social engineering.”

Gensler said in a statement that the rule will give investors the “consistent and comparable data” they have sought, while also giving companies the “flexibility to make decisions that best serve their shareholders.”

Nasdaq said in a statement that it is pleased the SEC approved the “market-led solution” and looks forward to working with companies on implementation. Nasdaq is hosting several

Data on corporate boards’ diversity is sparse, an issue that the Nasdaq rule aims to address by requiring annual disclosures.

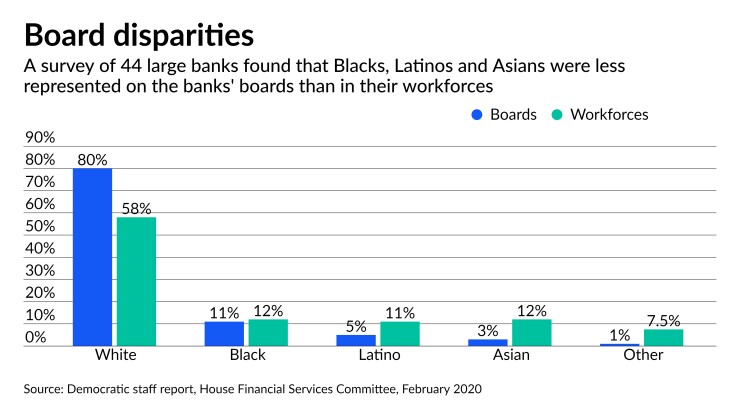

The aggregate data that does exist suggests that bank directors are predominantly white men. On average, about 70% of directors at some of the country’s largest banks are men, while 80% of directors are white, according to a report last year from the Democratic staff of the House Financial Services Committee. The findings were based on a survey of 44 large and regional banks.

Those banks’ boards did not reflect the full diversity of their employee bases, with Latino workers making up 11% of the banks’ workforces but only 5% of their board members, and Asian employees making up 12% of their workforces but 3% of directors.

Data on the sexual orientation or gender identity of corporate directors are even rarer. An analysis from the group Out Leadership found less than 0.3% of Fortune 500 board directors are openly LGBTQ.

Rep. Maxine Waters, the California Democrat who chairs the House Financial Services Committee, applauded the Nasdaq rule but said in a statement that the “work is not done.” She called on other stock exchanges to implement similar rules, and asked the SEC to require publicly traded companies to disclose more diversity data.

Nasdaq-listed banks will likely take a variety of approaches to meeting the new standards, said Anna Pinedo, a partner at the law firm Mayer Brown. “Lots of things will go into that calculus,” she said, noting that some companies may want to increase the size of their boards, while other firms might look to replace directors.

Banks will want to consider directors’ ages, their lengths of tenure, their different skill sets and other factors, Pinedo said.

Banks will have different deadlines and options to consider depending on their size. Some larger companies will need to have at least one diverse director — meaning a woman, person of color, or member of a religious or ethnic minority — by Aug. 7, 2023 and two by Aug. 6, 2025, or explain why they do not. For Nasdaq capital market companies, which tend to have a smaller market capitalization, the latter deadline is in 2026.

Smaller companies can meet the diversity objectives by having at least two women on their board, rather than one woman and either a director from an underrepresented minority group or one who is LGBTQ.

Nasdaq is saying that companies either have to meet those standards or explain why they have not, for which it says there is “no right or wrong” answer.

That is not much of a choice at all, the American Association of Bank Directors argued in a written statement. Some banks “should anticipate trouble” if they disclose that they have not met the new standards, the group said, and their biggest shareholders are institutional investors, proxy advisory firms and activist investors that have pressured banks to diversify their boards.

The bank directors’ trade group is updating its advice for members, given that its past guidance “not to discriminate based on race, gender, etc., but to choose directors solely based on merit” may no longer be suitable for many Nasdaq-listed companies.

Most companies will want to avoid disclosing that they do not meet the new standards, given that the public and investors would be “incredulous” that companies have been unable to find qualified board members within the transition period, said Christopher DeCresce, a partner at the law firm Covington & Burling.

To meet the standards, banks may “need to start thinking more broadly” — looking beyond their networks of local business leaders, who tend to be white men, DeCresce said. Those new approaches may include reaching out to groups that can connect banks with more diverse candidates and perhaps loosening the typical geographic restrictions.

Banking trade groups did not submit comment letters to the SEC as it was weighing whether to approve the Nasdaq rule. One banker, however, registered his opposition, saying the rule is “too rigid” and ignores individual companies’ circumstances.

Dennis Nixon, chairman of Laredo, Texas-based International Bancshares Corp. and CEO of the subsidiary International Bank of Commerce, noted that his company has several directors from underrepresented backgrounds, as well as several Hispanic women in top leadership roles at the company.

The $15.3 billion-asset bank had at least one woman on its board until May 2019, when longtime board member Peggy Newman retired, according to Nixon.

Adding a female manager to the bank’s board might be “viewed as unfavorable in regulators’ and some investors’ minds,” Nixon wrote in his letter, citing possible concerns about tilting the board too heavily toward bank insiders rather than outside voices.

He also wrote that Laredo’s size — the city has a population of roughly 255,000 people — makes it difficult to find a woman involved in the community who is willing or able to accept the time commitment that comes with a board seat.

“To satisfy the gender diversity requirement, IBC would likely have to recruit an independent director from outside its headquartered community which would place an undue burden of travel, expense and loss of time, for that director to travel to attend meetings,” Nixon wrote, adding that it is "very difficult to find, recruit and maintain" executives and other leadership talent.

The bank did not respond to requests for further comment.

Partly because banking is a closely scrutinized industry, it was challenging to recruit directors even before the Nasdaq rule was adopted, some observers say.

“The big challenge is that banks require a lot of preparation for the board meetings. It’s quite a heavy lift,” said Mary Caroline Tillman, who co-leads the global financial services sector at the executive search firm Russell Reynolds. “There’s also a lot of risk involved with these banks. If you go onto the board and something goes wrong, there’s a huge reputational risk.”

Still, Tillman supports the Nasdaq’s rule. She said that a diversity of thought and experience on a board can help discourage groupthink when it is added in a thoughtful and deliberate way. She also argued that more disclosure about diversity is generally good for investors, many of whom have sought this information in recent years.

The ratings agency Moody’s expressed a similar perspective. The Nasdaq rule would encourage transparency and board-level diversity and improve the consistency of disclosures for investors interested in environmental, social and governance issues, the ratings agency said in a recent research note. Companies with gender-diverse boards tended to be more highly rated, Moody’s said in a 2019 note.

Two analysts at Moody’s said in an email to American Banker that they anticipate no short-term risks arising from the Nasdaq rule. Given the focus on disclosure, “companies can’t be forced to comply,” wrote Brendan Sheehan, senior credit officer and lead governance analyst at Moody’s, and Fadi Massih, senior analyst and lead Nasdaq analyst.

Banks cannot reasonably expect to find the board candidates they want within a matter of months, according to Tillman. But they can start expanding their networks and looking at executives who could be ready to serve on a board a few years into the future.

“It’s no different than doing succession planning for your executive suite,” Tillman said. “Frankly, it surfaces a lot of really talented individuals who might not have even been thought about if you hadn’t opened the aperture."