Housing advocates and Democratic lawmakers in New York want to create more protections for tenants of rent-controlled apartments, but they are facing stiff opposition from property owners and the banks that lend to them.

Several proposals aimed at putting a lid on rapidly rising rents are under consideration in the state Legislature, including one that would abolish a provision that lets landlords raise rents on apartments by as much as 20% when they become vacant. A common complaint about the provision is that it encourages landlords to evict lower-income renters.

The legislation would cover properties throughout the Empire State, but it’s in New York City — by far the nation’s largest rental market — where the impact would be felt most acutely.

The Rent Stabilization Association, which represents property owners, has said that the changes would reduce landlords’ cash flow and prevent many from making needed repairs to older buildings, forcing them to raise rents on apartments that aren’t regulated by rent-control laws.

Bankers, meanwhile, worry that if the proposals become law, property owners could struggle to make loan payments and that some investors might lose interest in the city’s multifamily market.

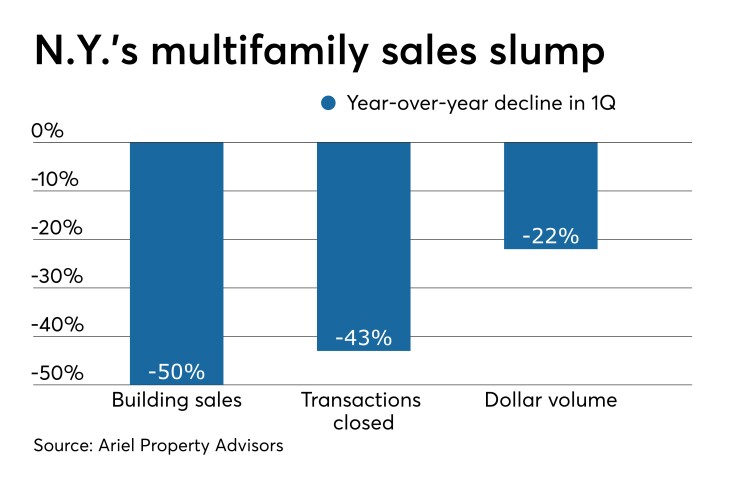

Indeed, many investors appear to be sitting on the sidelines, waiting to see how the battle over the future of rent control plays out.

In the first quarter,

“The proposals would put in pretty significant changes to rent control,” said Jared Shaw, an analyst at Wells Fargo Securities who follows a number of banks that are active in multifamily lending. Concerns about those changes “are definitely impacting the demand to buy multifamily properties until there is some clarity,” he said.

The New York State Senate Housing Committee is holding a series of public hearings this month on the legislation in Brooklyn and several cities in upstate New York. Observers have said that some form of the legislation is likely to be approved, since Democrats control both the state House and Senate and the governor's office.

Democratic leaders are scrambling to pass the new laws by mid-June, when current rent-control laws expire.

In New York City, more than half of low-income tenants

In an effort to slow the rate of rental increases, the New York City Council

State legislation is needed to further level the playing field for tenants, said Jaime Weisberg, senior campaign analyst at the Association for Neighborhood & Housing Development in New York, which supports the proposed changes to rent-control laws.

“It’s a matter of doing what’s right for tenants,” she said. “When someone leaves an apartment, you can raise the rent and you’ve made a windfall, but someone has also been displaced from their home.”

There’s also nationwide push to fight back against on landlords who try to juice profits by evicting tenants for the purpose of raising rents. A ballot referendum to enact

In New York City, tens of thousands of units are regulated through rent control or rent stabilization, a less restrictive form of rent control. Under rent-control laws, a landlord cannot raise a tenant’s monthly rent payment, provided certain conditions are met. The city’s rent-control laws were approved in 1947 to ensure a steady supply of affordable housing in the city.

For bankers, the effort to reform rent-control laws comes at an inopportune time. The Federal Reserve Board has indicated that it’s pausing rate hikes and could perhaps cut rates, which could trigger a spike in demand to refinance commercial real estate loans.

Uncertainty around the future of rent-control market is already having an impact at banks that are active in multifamily lending. At the $52 billion-asset New York Community Bancorp, the largest locally focused multifamily lender in the New York City market, with about $30 billion on its books at March 31, multifamily loan originations dropped 21% to $1 billion from the fourth quarter of 2018 to the first quarter of this year. New York Community did not return calls seeking comment.

The $49 billion-asset Signature Bank in New York is the second-largest multifamily lender in the market, with about $16 billion in loans, followed by the $27 billion-asset Investors Bank in Short Hills, N.J., and the $30 billion-asset Sterling Bancorp in Montebello, N.Y.

Joseph DePaolo, Signature's CEO, said he’s hopeful that elected officials will avoid a situation that could scare away investors and developers.

“They’re not going to drive business out,” DePaolo said during the bank’s first-quarter earnings call last month. Gov. Andrew Cuomo “doesn’t want to turn business away.”

A Signature Bank spokeswoman said executives were not available for additional comments.

The goal of the proposals is not to make it harder for landlords to conduct maintenance or make large capital improvements, but to root out bad actors who created business models based on evictions and subsequent rent hikes, Weisberg said.

“If you’ve been making loans responsibly, you shouldn’t have anything to worry about,” she said.

Kenneth Ceonzo, the chief financial officer at Ridgewood Savings Bank in Queens, said the proposals don’t worry him because the $5.5 billion-asset mutual bank underwrites loans based on the size of rent payments at the time loans are closed. Ridgewood never projects that its loans will generate higher cash flow levels after current tenants are evicted, he said.

“We only lend against actual rent-roll data and we never assume those rents will be converted from rent-control status” to a monthly payment based on prevailing market rates, Ceonzo said.

But many multifamily lenders in New York have a legitimate reason to be concerned if the new rules take effect, said Ely Razin, the CEO of the commercial real estate data provider CrediFi.

“The minute you approve a law that suppresses a landlord’s revenue, that will impact the bank,” Razin said. “Instead of assuming a landlord is going to have rent growth, they’re going to ask whether they want to issue them a loan at all.”