Most big U.S. banks say their portfolios would withstand regulatory scrutiny of climate risk, even though the industry is still in the early stages of making the changes necessary to measure its exposure.

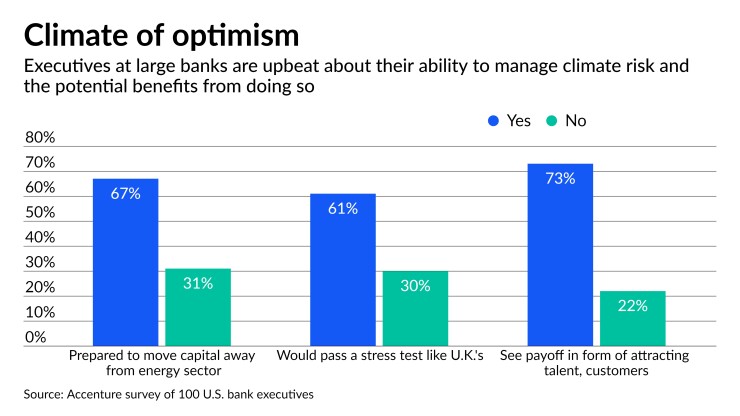

In a recent Accenture survey of executives at the nation’s 50 largest banks, 61% of respondents said their institution would be prepared to comply with climate risk disclosures and scenario tests like those currently happening in the United Kingdom, while just 30% said they would not.

But even the most committed banks will be challenged to find, analyze and model the non-financial data needed to show the climate risks in their own portfolios, risk experts say.

“I don’t think they’re fully aware just how hard this nut is to crack,” said Steve Culp, Accenture’s Global Digital Risk and Compliance lead. “Where we are in the climate space and the broader ESG agenda is that the data is just soft, it’s unproven, it’s inconsistent and it’s not fully understood.”

Climate risk can be sorted into two categories: physical risks, or those arising from a changing climate and serious weather events, and transition risks, or those resulting from a transition to a lower-carbon economy. But some loans and investments are easier to assess than others, depending on what type of information the lender has collected about those borrowers.

For example, a portfolio of residential mortgages in a coastal area might be easier to assess because the lender would have collected granular details about the property at the time it made the loan. It could be much harder to gauge the risks associated with a credit line made to a firm with dozens or hundreds of locations, particularly if the lender does not know where each and every office is.

Banks also need to determine which climate risks are the most material for their own businesses. And they need some uniformity in how those risks are reported, so that they can better understand how they compare with their peers.

The Biden administration

Even before the executive order, the Federal Reserve

Some Republican lawmakers, particularly those from major energy-producing states, have criticized these efforts as regulatory overreach. They and other critics say the focus on climate risk politicizes access to financial services, and that banks and banking regulators are not qualified to evaluate non-financial risks.

“If Congress believes current environmental policies do not adequately address climate-related risks, changes should be enacted through the legislative process — not through financial regulation," Sen. Pat Toomey of Pennsylvania, the top Republican on the Senate Banking Committee,

The industry itself is split on the matter. Big banks are generally supportive of the SEC’s plan, though they have asked for a safe harbor limiting legal liability for unintentionally misleading disclosures.

Community bankers

Across the Atlantic, the Bank of England recently launched

The Prudential Regulation Authority, which is part of the Bank of England, is asking firms to embed climate-related risks by the end of 2021.

U.K. regulators have said that their intent is to get a sense of the risks climate change poses to the country’s financial system, and that they do not intend to use the results of the stress test to set capital requirements. They plan to announce the results of the exercise in May 2022.

Seeking a better understanding for how U.S. bank executives are managing climate risk, Accenture surveyed 100 bank executives, most of them C-suite roles, in May. Nearly two-thirds of the respondents, or 64%, said they had the granularity of data needed to assess the climate risks associated with their lending decisions, while 35% said they did not.

In addition, 73% of respondents said that managing climate risk and promoting a transition to a green economy are important for attracting employees and customers.

Culp said he had anticipated a much more defensive posture from U.S. banks, particularly given the relative immaturity of climate risk analysis in the U.S. versus overseas markets.

Accenture’s survey covered some U.S. subsidiaries of foreign parent companies, which is arguably the swath of the industry that has gotten most comfortable with the idea of measuring and disclosing climate risk to investors.

While 67% of the respondents said they are prepared to move capital away from the energy sector as part of a transition to a low-carbon economy, that shift may not happen right away, Culp said.

“We all recognize that many institutions are making positive statements in the marketplace,” he said. “When you follow the money, the money doesn’t always catch up to the words as fast.”