-

With mortgage rates climbing in recent weeks homeowners have switched from feverishly pursuing refinancing to buying new homes, a Federal Reserve Board report said Wednesday.

July 17 -

The long-anticipated collapse in mortgage applications, finally a reality, stands to take a bite out of bank earnings in the second quarter and beyond.

July 10

As

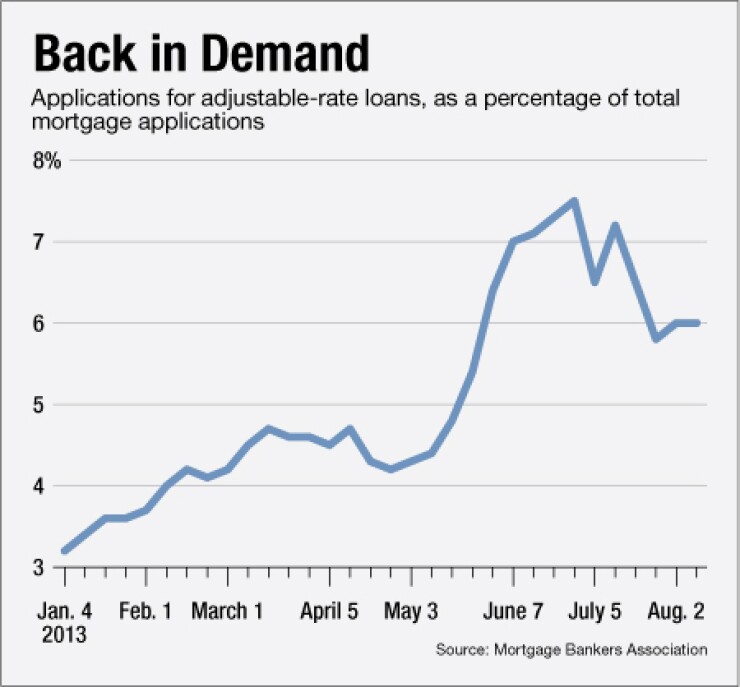

Applications for adjustable-rate loans now make up 6% of mortgage loan requests, up from 3% at the beginning of the year, though still well below the 32% peak in 2004, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association.

Choosing an adjustable-rate mortgage would seem counterintuitive when interest rates are rising. But the spread between average starting rates on hybrid ARMs and 30-year fixed mortgage rates has widened in the past few months, making the ARMs more attractive for borrowers who want to cut their monthly bills. (Hybrid ARMs have rates that are set at a fixed rate for a limited time typically five or seven years before resetting higher.)

"Banks are definitely doing more ARMs because they're selling the consumer what they're asking for, which is a lower monthly payment," says Bob Caruso, an executive managing director at Lender Processing Services. "It's like it was several years ago where customers buy the lowest possible payment, not knowing the consequences."

Many borrowers with adjustable-rate mortgages were among the first to default during the downturn. When their rates adjusted after an initial teaser period, they were unable to refinance and got stuck owing sharply higher payments.

This time around will be different, lenders say, because underwriting standards are tougher for hybrid ARMs, so borrowers will be less likely to get squeezed when interest rates reset. Moreover, regulators have

"The world has changed since 2003 and underwriting standards are much higher," says Cameron Findlay, the chief economist at Discover's (DFS) home loans division. "You still want to ensure that the consumer has the ability to repay and that we're not setting people up for failure."

Since May the average fixed rate for a 30-year mortgage has climbed 110 basis points. As a result, the percentage of conventional borrowers eligible to refinance has dropped to 30% from more than 80%, says Scott Buchta, head of fixed-income strategy at Brean Capital.

"The low-hanging fruit is gone, so lenders have to dig a little deeper. They're looking to keep the pipelines full," says Buchta. "Lenders are pushing ARMs right now because so many fixed-rate borrowers are out of the money," meaning they would not significantly cut their expenses by refinancing into a fixed-rate loan.

Caruso agrees that ARMs are much less risky today and can save savvy borrowers money over the life of the loan. A former servicing executive at Bank of America (BAC) and Wells Fargo (WFC), he

Still, Caruso sees risks, mainly that unsophisticated borrowers may not understand what happens when rates reset. "They could have some payment shock down the road," he says.

About a month ago, Quicken Loans moved ARM pricing to the top of its rate sheet provided to third-party mortgage bankers and brokers. Quicken is offering a 5-year hybrid ARM at 2.99%, compared to a 15-year fixed-rate at 3.37%, or a 30-year fixed at 4.5%.

Bob Walters, Quicken's vice president of capital markets, says

"For many folks, it makes a lot of sense to take a shorter-term product," Walters says. "If the borrower is in a situation where they're not going to be in that home for more than seven years, it would be incorrect for them to take the fixed rate when the ARM is giving them a benefit of lower monthly payments."

Most homeowners stay in their homes an average of 13 years before moving out, down from 20 years in 2009, according to a study by the National Association of Home Builders.

After the crisis, Fannie Mae set

Walters disputes the notion that ARMs contributed to the financial crisis.

"ARMs were a contributor to getting us out of it because anybody who had an ARM in the last five years saw their rate drop dramatically," he says, arguing that the shoddy underwriting of subprime loans was the primary contributor to defaults. "If I do terrible underwriting, the loans will go into default."