A decade ago, the wholesale origination channel was in full meltdown, a nuclear waste pile that few lenders wanted to be associated with.

Today, the four large bank mortgage lenders still keep their distance. None of them have a direct wholesale lending channel, though as correspondent aggregators, they will buy brokered loans sold to them by other wholesalers.

But for small and midsize lenders — depositories and independent mortgage bankers alike — wholesale lending has again become an attractive option to expand residential real estate lending. The shift comes at a time of soaring costs and an originations market expected to decline for the second straight year.

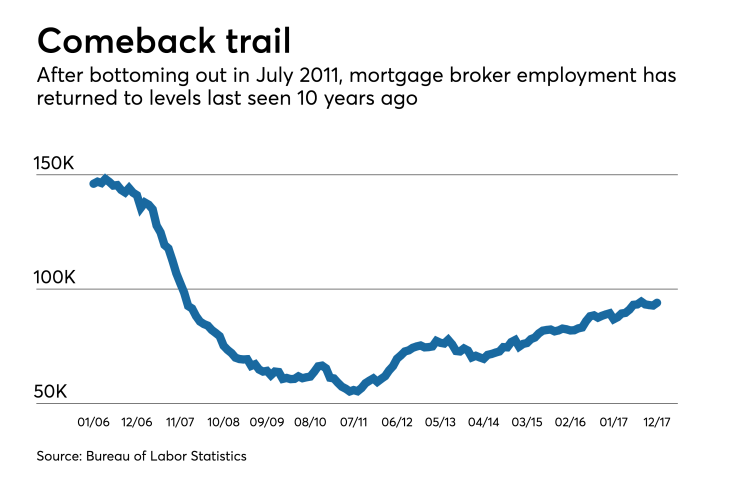

This increased flow of capital to the wholesale channel has sparked a renaissance for mortgage brokers. Employment in the sector peaked at 148,200 workers in April 2006, before falling to a post-crisis trough of 55,200 in June 2011. Since then, brokers have been on the rebound, growing to 94,000 in December 2017, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The mortgage broker business never fully went away after the crisis. But high compliance costs, combined with fewer outlets to fund loans and securitize them, changed the economics of the business. It became difficult, if not impossible, for many of the smaller broker shops to remain in business.

But now, the industry is taking a fresh look at mortgage brokers as it searches for ways to lower its own origination costs and increase market share.

There are a number of reasons brokers bore the brunt of the fallout from the mortgage crisis. The decimation of broker employment started with the downfall of large wholesalers, particularly those willing to fund the most exotic and risky mortgages during the boom years. Capital dried up to fund new loans and brokers had few options to stay in business.

Then came the blame game. As the world sought to explain how a housing bubble metastasized into a full-blown economic meltdown, vocal critics within the mortgage industry, consumer advocates, politicians and others placed the blame squarely on brokers.

Brokers — which at their peak arranged nearly two-thirds of all mortgage originations — were painted as unsophisticated and underqualified participants, with a financial incentive not to act in borrowers' best interests. Brokers, critics claimed, stretched the boundaries of already lax underwriting standards because their compensation was tied to loan volume, rather than the long-term performance of the mortgages they arranged.

"My biggest mistake, probably of my whole career was not closing down our mortgage broker business sooner."

— Jamie Dimon, JPMorgan Chase Chairman and CEO

Meanwhile, the few brokers still in business countered that wholesalers and their Wall Street securitizers were responsible for establishing underwriting standards and they were the ones who got greedy. But that argument fell on deaf ears, particularly compared to the words from the head of one of the largest precrisis wholesalers.

"My biggest mistake, probably of my whole career," JPMorgan Chase Chairman and CEO Jamie Dimon said in 2009, "was not closing down our mortgage broker business sooner."

It didn't help that the broker sector was mostly made up of small organizations or even single originators in business for themselves. So while large financial institutions deemed "too big to fail" received large financial bailouts, the relatively fragmented broker sector was left to fend for itself.

To be sure, the entire mortgage industry now faces far greater regulatory scrutiny and compliance obligations. But times have changed, and brokers and wholesalers have implemented the process changes necessary to operate in the new environment.

For example, there was some initial confusion over whether brokers or wholesalers would issue and be responsible for the accuracy of the new Loan Estimate disclosure to borrowers under the TILA-RESPA integrated disclosure rules. More than two years later, while practices may vary, the parties have some certainty what they are doing passes muster.

One regulatory change that actually helped brokers was the Secure and Fair Enforcement for Mortgage Licensing Act, which requires all loan officers to register with the Nationwide Multistate Licensing System and undergo background checks. It also requires testing and continuing education for loan officers at nonbank lenders and brokers.

There's a sense among many origination professionals that the SAFE Act created a more professional environment in the industry, particularly among brokers.

The shift to a purchase market is another reason for banks to get into wholesale. "Brokers have great relationships in local markets with real estate markets and the local trusted advisors," said Kristy Fercho, Flagstar Bank's president of mortgage, adding that it gives the bank access to different players in those markets.

Mortgage brokers having multiple outlets for their product benefits the wholesaler as well, she said. The broker is not trying to tailor an application to get it to fit into the bank's guidelines; that loan can be taken to a more appropriate funding source.

"It really allows the bank to stay true and committed to what their credit profile is and not feel the pressure [from its own retail loan officers] to go down the spectrum in terms of product diversification," Fercho said. Rather, the bank operates within its risk appetite when purchasing a brokered loan.