Sometimes it feels good to let go.

Such is the case at Bank of the Ozarks in Little Rock, Ark., which recently did away with its holding company in a move designed to streamline numerous processes and create more efficiencies.

Some might view the move as contrarian; over the past two decades banks have tended to form holding companies rather than dissolve them. But George Gleason, Bank of the Ozarks’ chairman and CEO, and some industry observers believe more management teams could have reason to follow the bank’s lead.

Bank holding companies are a “vestige of the past” and are no longer needed, Gleason said.

“The redundant administrative, accounting and regulatory cost of that infrastructure was really just wasted money,” Gleason said, comparing the decision of maintaining a holding company to owning a second home.

Gleason isn't the only person warming up to the idea.

"Investors should consider which other banks could replicate [Bank of the Ozarks'] initiative and eliminate their BHC structure," Christopher Marinac, an analyst at FIG Partners, wrote in a recent note to clients. "We think many organizations could find this appealing."

Financial institutions, especially those like the $20 billion-asset Bank of the Ozarks that have simplified business models, may not need a holding company, said Chip MacDonald, a lawyer at Jones Day in Atlanta. A basic bank structure could suit an institution that isn’t heavily involved in nonbanking activities.

The Dodd-Frank Act may have also reduced the need for smaller, privately held banks to form holding companies, in part by restricting the use of trust-preferred securities as capital, MacDonald said. Previously, banks would use those hybrid securities to boost capital at their parent companies.

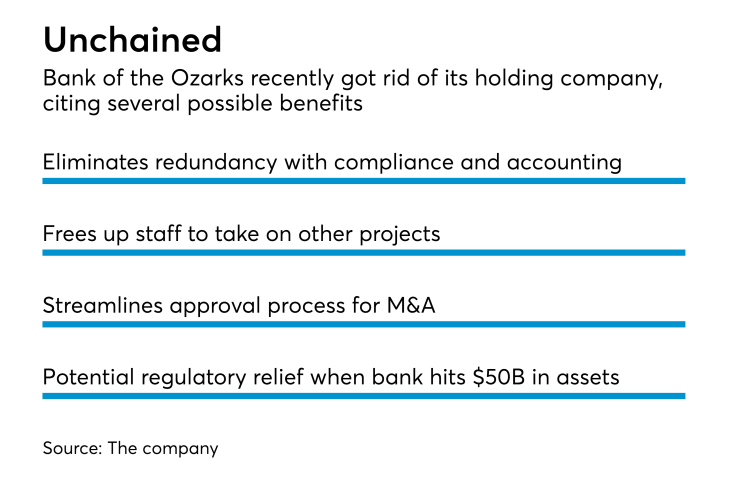

Gleason, for his part, can rattle off a list of perks tied to dissolving the holding company.

The move reduced redundancies, freeing up employees to work on other projects. For instance, Bank of the Ozarks’ staff no longer has to prepare quarterly and annual reports for the holding company.

Doing so creates “additional capacity to take on more workload as our company grows,” Gleason said.

The absence of a holding company should also streamline acquisitions at Bank of the Ozarks, which has bought eight banks since late 2012, including last year’s purchases of C1 Financial in Tampa, Fla., and Community & Southern Holdings in Atlanta.

Bank of the Ozarks, by dissolving its holding company, will not need approval from the Federal Reserve for most acquisitions, which could reduce the time between a deal’s announcement and completion. That gap was about eight months for C1 and nine for Community & Southern.

“We really don’t see any negatives,” Gleason said.

Bankers will need to do their homework before drastically changing an institution’s structure, Gleason warned. A big focus should be placed on banking laws in states where an institution operates.

Bank of the Ozarks worked with Arkansas legislators, the governor and the bankers association to have 11 changes made to the state’s corporate and banking laws so it “could do everything for our shareholders ... as a publicly traded bank,” Gleason said.

Arkansas law, for instance, didn’t allow state-chartered banks to count preferred stock and subordinated debt as capital, which “you would want to have in your toolbox as a publicly traded company,” Gleason said.

Other changes involved “modernization and technical improvements,” he said.

Gleason, meanwhile, has been fielding calls from other bankers (he did not name them) who want to learn more about Bank of the Ozarks’ experience.

“We’ve had a number of inquiries,” Gleason said. “There’s a level of interest out there.”