The banking industry attracted an influx of corporate deposits during the third quarter, and new money market regulations were a big reason why.

But it's a mixed blessing at a time when loan demand is spotty and the Federal Reserve is not expected to raise rates until December (probably). Instead, the extra deposits will likely provide an unwelcome drag on banks' fourth-quarter margins before starting to flow elsewhere early next year.

Two big banks — U.S. Bancorp and JPMorgan Chase — in recent weeks pointed to money market reform as a factor behind their fast-growing deposit bases. At least one analyst has cited the new rules as a driver of strong deposit growth at regional banks as well. The securities rules, which took effect Oct. 14, made sweeping changes to the way certain types of funds price shares and charge fees.

The change threw corporate clients for a loop, and it pushed them ahead of the deadline to move cash into checking accounts and certain money market funds (typically offered by banks) that were unaffected by the regulations. Banks, meanwhile, attracted new sources of deposits from outside the industry.

It's unclear how long the deposits will stick around, but it might not be very long.

"It's early days, so it's hard to know," said Sean Collins, an economist with the Investment Company Institute, a trade association that represents mutual funds and other investment firms. Collins noted there was "a lot of uncertainty" in the market before the new rules took effect.

U.S. Bancorp saw a spike in deposits in September, shortly before the new rules too effect, according to Terry Dolan, chief financial officer at the Minneapolis company. But Dolan said he expects the influx to be short-lived, lasting into the fourth quarter but not long into 2017.

"We see this as a little more transitory at this point in time," Dolan said in an interview following the company's quarterly conference call with analysts.

Money market reform is just one of several factors prompting deposits to grow faster at big banks than at their smaller peers. New liquidity requirements, as well as advances in technology, have also contributed to the strong quarterly growth.

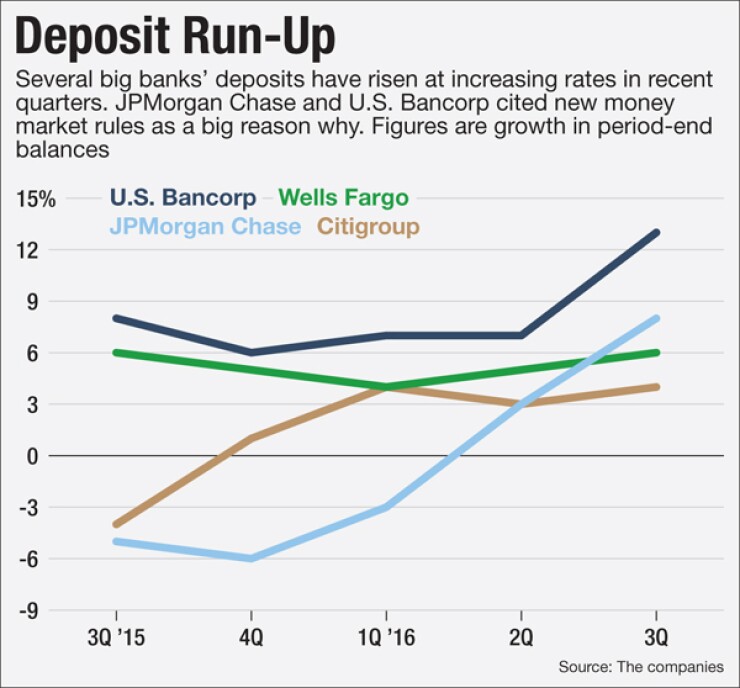

Deposits swelled at big banks at a particularly rapid clip during the third quarter. U.S. Bancorp increased period-end deposits by 13% year over year, to $317 billion. That was nearly twice the pace in the second quarter.

Similarly, JPMorgan's deposits grew by 8% in the third quarter, compared with 3% in the second quarter.

"I think one of the principal reasons … is money market reform," Andy Cecere, president and chief operating officer at the $454 billion-asset based U.S. Bancorp, said during the company's quarterly conference call.

The new rules were also a factor behind strong deposit growth at large regional banks across the industry, Peter Winter, an analyst at Wedbush Securities, wrote in an Oct. 31 note to clients.

Under the new rules, prime money market funds — which invest in corporate debt — and tax-exempt funds — which invest in municipal securities — are subject to a host of changes.

Both types of funds mare now required to use a floating net asset value to quote their shares, rather than a constant $1 price. The funds are also allowed to impose certain fees and other restrictions to prevent withdrawals during periods of market volatility.

The rules are designed to prevent the widespread redemptions experienced by money market funds during the financial crisis.

Still, they pose a series of logistical headaches for corporate cash managers, according to industry experts. Using a prime fund may have tax implications, requiring a company to record a gain or a loss on a daily basis as it makes redemptions. Many companies are not yet equipped to handle that type of accounting.

"That's just a nuisance," Collins said.

Additionally, some institutional investors — including some hedge funds — are prohibited under their bylaws from using funds with a floating net asset value, Dolan said.

The market reaction to the new rules has been clear: Over the past year, about $1.1 trillion has migrated out of prime and tax-exempt funds, according to ICI.

The shift has been a boon to the banking industry.

Most of the cash that has migrated away from prime funds has been reinvested in government funds, which are unaffected by the new rules and widely offered by banks, according to ICI.

During their quarterly calls, executives from both U.S. Bancorp and JPMorgan, in particular, noted sharp increases in their government funds. Executives at U.S. Bancorp said the company's government fund balances increased $9 billion prior to the SEC rule change, while its prime fund decreased by about $6 billion.

Clients have also transferred significant amounts of cash into corporate checking accounts, according to Dolan.

"We saw that happening throughout the year, but particularly in September, as a number of customers and institutional clients were starting to make decisions as to what they were going to do," Dolan said.

Most industry experts view the influx of corporate deposits as fleeting, lasting into the fourth quarter but dissipating into 2017.

There are a number of reasons why. As clients grow more comfortable with prime funds, they may move balances back to prime accounts outside the banking industry. It could also take several months for institutional investors to amend their bylaws, as necessary, to use funds with a floating value.

In the fourth quarter, however, the influx of deposits at big banks will "cosmetically" put pressure on margins, pushing total deposits to grow at a temporarily inflated pace, according to Marty Mosby, an analyst with Vining Sparks.

At U.S. Bancorp, the influx of deposits tied to money market reform contributed to a 3-basis-point compression in the company's net interest margin from the prior quarter, Dolan said at a Nov. 4 industry conference.

In the coming year, deposit growth at big banks will likely slow down, as clients grow accustomed to the new rules and move funds out of the banking industry, according to Mosby.

Still, he said some of the influx in corporate checking accounts could stick around as clients look for stable places to park their cash and earn a predictable yield.

"I think we, obviously, did get some good inflows … in terms of money market reform into our government fund," said Marianne Lake, the CFO at JPMorgan, when asked during the company's earnings about deposit growth. "But we also have been very focused in our other wholesale businesses on continuing to attract operating deposits," Lake said.