You could easily mistake Anne Leland Clark, a Twin Cities nonprofit executive, for a banker with big, national ambitions as she discusses her organization’s digital platform for the underbanked.

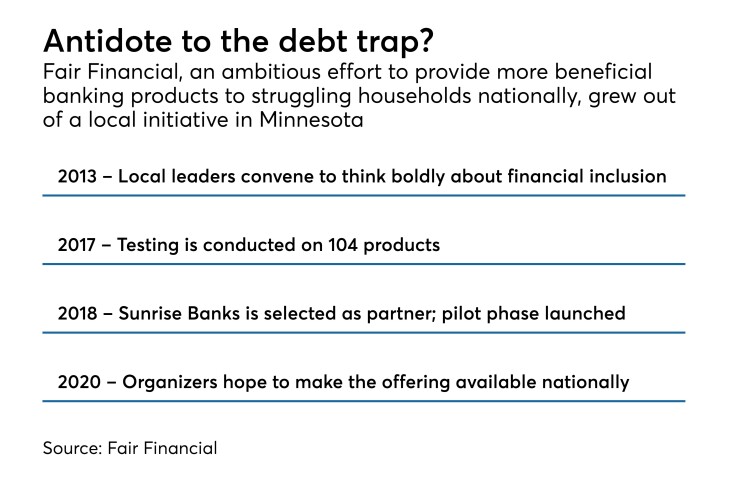

The product, known as Fair Financial, launched in a pilot program this week to serve about 500 local customers over the next 18 months. But Clark and her partners — including at Sunrise Banks in St. Paul — have no plans to stop there, having established a goal of providing 5,000 low-income customers across the country with Fair deposit accounts and small-dollar loans by 2020.

It’s a big aim for a small nonprofit — and it illustrates one of the many ways that new technology is being used to bring people with blemished credit back into the banking system.

“We want to go to where people live, work and worship,” said Clark, whose St. Paul-based organization, Prepare + Prosper, is overseeing the rollout of the Fair banking platform.

What sets Fair apart in the industry is what Clark and others describe as a “bundled” suite of products for the underbanked. Customers can open low-cost checking and savings accounts, as well as take out a small-dollar loan that’s designed to help them bolster their credit scores. The accounts are provided through a cobranded partnership with Sunrise Banks, a $1.1 billion-asset community development financial institution in St. Paul.

Perhaps more important, though, is Fair’s distribution model. Customers will open the accounts at social service agencies, nonprofits and even, in some cases, through their employers. The idea is to establish a sense of trust at the outset — and, over time, discourage customers from using high-cost financial alternatives, such as check cashers and payday lenders.

“Through this relationship model, we want to rebuild those seeds of trust that have been broken with financial institutions,” said Clark, director of financial capability and learning at Prepare + Prosper, an organization that provides free tax preparation and financial advice to low-income communities in the Twin Cities.

To expand nationally, Clark and her colleagues are exploring ways to offer the accounts through national nonprofit organizations, such as the United Way, the National Urban League and community action networks.

The launch of the Fair banking platform comes as big banks — such as

For people who have either never had a banking account, or who have struggled to maintain good credit scores, visiting the bank — a place where employees are dressed in suits — can be intimidating, according to Clark, whose organization designed the Fair platform based on consumer feedback. Opening an account with a social worker or employer can make all the difference in bringing them back into the traditional financial system.

“We have no sales goals,” Clark said.

Whether Fair takes off in the years to come remains to be seen. The project has the financial backing of big philanthropic players, including the JPMorgan Chase Foundation and the McKnight Foundation, which are covering the cost of the platform's development and expansion.

Sunrise Banks, meanwhile, will collect revenue from the bank accounts, including a $3 monthly service fee on the Fair checking accounts, as well as an 8% interest rate on the small-dollar loans.

The loans, notably, are a hybrid product that also encourage customers to save. The loan funds — which max out at $500 — will be placed in an 18-month CD. Over that period, customers will set aside $30 per month to pay off their loan. By the end of the 18 months, they will collect their loan, plus the interest earned on the CD, and be able to use the funds however they choose.

“Bundling these services not only offers a more complete experience for the underbanked, it makes banking simpler and a much more efficient experience,” David Reiling, Sunrise’s CEO, said in an email.

As the Fair platform prepares to launch on a national stage, Clark and her colleagues are keeping an open mind about how to modify it in the years ahead. Depending on consumer needs, it could include additional lending or advisory services.

Alternative revenue models are also on the table. While the platform is partially funded by philanthropic donations, the group may look for more sustainable sources of revenue over time, such as charging for-profit companies for offering the service to their employees.

Brenton Peck, a senior manager at the Center for Financial Services Innovation in Chicago, which assisted Fair in 2014 in its initial market research, said he hopes the product will ultimately include a service to help customers with longer-term financial planning.

But for now, he said, the initiative has what it needs to set its sights on a national footprint.

“You’ll find a lot of high-quality products that are out there,” Peck said, pointing to low-cost, digital checking accounts at big banks. “But it’s few and far between when you see consumer needs packaged together on one platform like Fair — and that’s why it’s scalable.”