(From Bank Investment Consultant)

Selecting the right separate-account manager for a client may be the most important decision an adviser must make, as executives at a superregional banking company and a community bank can attest.

Bill Stone, a senior vice president and the director of PNC Financial Services Group Inc.’s wealth management division, said his advisers’ menu of managers is selected by a research group within the division that considers five factors: people, process, performance, business structure, and compliance.

“We’re looking at the individual responsible for management of the fund, his or her background, tenure, experience, and whether the people responsible for past performance are still there,” he said. “We look at the depth of the team and how stable that team has been.”

David Maynard, the director of wealth management at Southern Community Bank in Winston-Salem, N.C., is still in the early stages of building a separately managed account business. He has built it solely through the bank’s commercial officers; when they talk to a potential client about lending, he attends the meeting to talk about investment opportunities.

Offering a managed account lets him deliver better service and performance while enhancing the commercial relationship, he said.

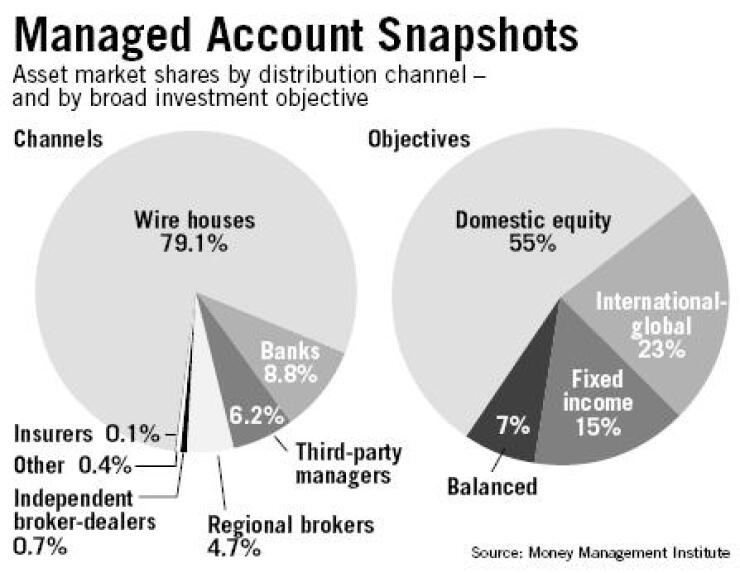

Separately managed accounts are a business that about 70% of advisers say they wish to tap, according to Financial Research Corp. in Boston. At March 31, assets in managed accounts grew 8.6% from a quarter earlier and 24.8% from the year earlier, to $736.4 billion.

Though this is only about one-tenth of the assets held in mutual funds, it shows an appetite among the wealthy — managed account minimums per manager are still mostly in the $100,000-$250,000 range — for a product that lets them customize their investments to take into account their existing holdings and tax liabilities.

Managed accounts work well for the wealthy, but they also help advisers build fee-based business, and banks are eager for the recurring income the accounts provide. But overseeing these accounts requires more than ordinary depth and sophistication.

Bankers must ask themselves, what does the client need a managed account to do? If a high-net-worth investor has a lot of money in large-cap stocks, some in small-cap ones, and very little in midcaps, is a managed account the best vehicle for allocating assets?

If it is just a matter of filling a portfolio gap, “advisers shouldn’t think of any one investment vehicle as a magic bullet,” said Steve Deutsch, who manages Morningstar Inc.’s separate accounts business in Chicago. “The adviser’s job is to think things through to the next level to find the best solution,” whether it is a separately managed account, a mutual fund, or an exchange-traded fund. “Advisers must think about the individual client and not confine themselves to one kind of offering.”

But separate account managers should be expected to have the skill to outperform the benchmark in their market. Advisers must decide how to measure a manager’s performance and determine whether the manager adds enough “alpha” to justify the cost.

Mr. Stone said the overriding theme at PNC is consistency, which goes hand in hand with performance.

“We also look at how the manager has added value in the past and what has been done to reduce risk,” he said. “Some managers are not performers, but they offer a smoother ride, which is appropriate for some clients based on their risk tolerance. Lastly, we look for consistency of approach.”

When considering risk and return, Mr. Stone said, good performance can come at too high a price for clients of a conservative bent. “Some clients may tolerate a more aggressive manager; others can’t take the gyrations.”

The Pittsburgh company considers business structure — the ownership of an investment firm, a manager’s tenure, and whether the manager has a personal stake and is thus more likely to stay.

Mr. Stone also wants to know how the firm deals with legal and compliance issues. “Maybe the firm has the type of culture we don’t want to be involved with.”

When it comes to managers who have already been brought in, Mr. Stone said that as long as they are doing what they promised at the outset, patience on the client’s side of the table is a virtue.

“Underperformance often comes down to the manager’s underlying substyle. We bought them for that substyle, so we understand. If nothing has changed in the manager’s investment style, we’ll give it quite a bit of time,” he said. “However, if a manager has outperformed the index, but there has been some style drift, we’ll pull the plug pretty quickly.”

Mr. Stone recently worked with a client who is an executive of a public company. “I talked to him about what he was trying to accomplish,” he said. “He has very large holdings in the stock of his previous and current employer, both basic materials companies. He wanted to retire on a certain income, most of which would be covered by his pension, so our conversation was largely about his estate and what he wanted to leave behind.”

Since the client had a huge holding in basic materials, Mr. Stone said, he needed to build a large-cap stock portfolio with a less cyclical linear correlation. He also used bonds and small-cap, mid-cap, and international stocks, plus a hedge fund of funds and private equity exposure to round out the portfolio.

PNC wealth managers typically meet with clients at least twice a year, Mr. Stone said. The wealth management division uses a menu of 25 to 30 managers at any one time. The managers have 100 relationships at most, and the average managed account size is $1 million. Advisers can use any combination of managers.

So far, Southern Community’s Mr. Maynard has 20 relationships — half individual and half corporate — with an average account size of $1 million. His operation manages $120 million of brokerage assets, but it began to focus on wealth management only last year. Nevertheless, he brought in $10 million of managed money that year and is on track to do the same this year.

Most of what he does on the corporate side is fixed-income investing, for which he uses individual managers.

“One company opened a $1.7 million account recently that wanted all of its money with a fixed-income manager,” he said. “Sometimes we use balanced managers, but this account is mostly in government, double-A, and triple-A bonds. We tend to have very conservative investors at this bank, and that’s certainly the case with our corporate clients.”

Closing that deal took about a month of joint meetings with commercial officers to pin down what the client needed, Mr. Maynard said. He chose a money manager at a $2 billion firm that only does fixed income. Since the manager buys at institutional prices instead of retail, the client ended up with a portfolio tailored to its goals — and saved money, he said.

“The minimum for a managed money account at our broker-dealer is $100,000, although I don’t look at that option unless a client has at least $250,000, because it’s difficult to get the necessary diversification below that,” he said.

Southern Community has access to 40 to 60 managers on its various platforms through the broker-dealer Uvest Financial Services Inc. Mr. Maynard said he chooses the most appropriate manager for his clients by considering performance, manager tenure, and risk ratios.

“I manage toward risk, so I look for ratios that are substantially below those of the market,” he said. “I also look for manager accessibility; it’s nice to use a manager a client can actually talk to. For this reason, I’ll use managers in our region or at a firm with a rep nearby.”