WASHINGTON — When the coronavirus pandemic hit the U.S. economy in March, some banking industry watchers

The default rate on leveraged loans reached 4% in July, according to S&P Global, higher than the 1% rate set a year earlier but nowhere near the double digits some had predicted from the crisis. A March report by Fitch Ratings had projected a cumulative 15% default rate in 2020 and 2021.

Some have attributed the benign default numbers to tightened lending standards, higher fees for corporate borrowers and a decline in overall leveraged loan issuance. Meanwhile, relief for businesses provided by the $2 trillion stimulus package in March helped stabilize credit quality, observers say.

But a

“At some point in the new year, you're going to see that some businesses just … need additional support,” said Ellen Snare, a partner at King & Spalding.

Leveraged loans skyrocketed following the 2008 financial crisis and are estimated globally now to total

Many saw the coronavirus crisis as having the potential to lay bare the risks of the leveraged lending market.

In the low-interest-rate years following the 2008 financial crisis, a record amount of businesses have loaded up on debt, and the global leveraged loan market is estimated to be

Before COVID-19, the default rate on leveraged loans was remarkably low. And although data has suggested that delinquencies may be rising — and even topped 4% in July by issuer count, according to S&P Global —so far they are not to the extent that may had originally feared when the pandemic plunged the U.S. economy into a recession.

“I was a little bit surprised that there were not more defaults,” said Erik Gerding, a professor at the University of Colorado Law School.

But without more support from Congress to provide economic relief to businesses, there could be a dangerous trickle-down effect, said Snare.

"If there isn't fiscal stimulus available to them in the new year, and if lenders don't see the pieces that the borrower is putting forward, there may not be sufficient support to keep them afloat,” she said.

Banking regulators have long warned that leveraged lending could pose a risk to financial stability. Although some have said that their concern is concentrated in nonbanks' steadily increasing share of the leveraged loan market, data has shown that leveraged loans on banks’ books

The Fed’s response to the pandemic — which included lowering interest rates to near zero and deploying nearly a dozen emergency lending facilities — has so far helped to keep defaults largely at bay, said Walter Mix, head of the financial services practice at Berkeley Research Group and a former California banking commissioner.

“Of course, the low-interest-rate environment is a two-edged sword, where margins are significantly impacted, but at the same time, the low rates are helping many of these loans to perform better than they otherwise would,” he said.

Snare said she believes most of the activity around leveraged loans that occurred in the third quarter was related to refinancing as opposed to new issuances.

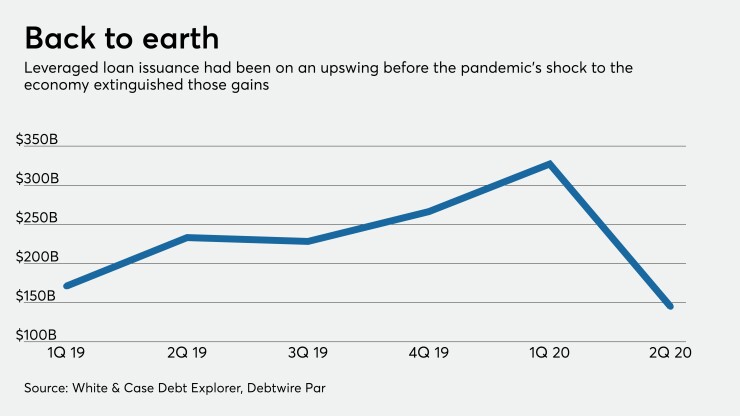

That trend that was also present in the second quarter, where the issuance of leveraged loans was about $113.8 billion, down from $271.5 billion in the first quarter, according to Refinitiv LPC. Similarly, a recent report by the law firm White & Case said U.S. leveraged loan issuance in the second quarter totaled just under $145 billion, a sharp 55.7% drop from the previous quarter and a 38% decline from a year earlier.

Lenders tightened standards across all loan products at the onset of the pandemic. Most banks reported that they began

Heavily indebted borrowers that may have looked for loans in the first half of 2020 may have encountered higher fees and lender-friendly protections, which may have led them to seek support elsewhere.

Managers of collateralized loan obligations are also paying more to borrow from debt investors compared to before the pandemic, which has prevented issuance of leveraged loans from rebounding, according to S&P Global.

But the near-zero interest rates may still be encouraging lower-rated businesses to take on more debt, said Gerding. And given the very uncertain economic outlook, it’s unclear how soon many companies will be able to pay those loans off.

“The market has sort of restarted, and it's being used not just for economic recovery, but actually to pay dividends to private equity investors,” Gerding said.

In the past, some policymakers have downplayed the risks that leveraged loans pose to the banking system because they argue it’s primarily hedge funds, insurance firms and other nonbanks actually originating the loans. But banks are still exposed through prime brokerage, credit derivatives and investments in collateralized loan obligations, which are made up of leveraged loans.

“The issue is, who lends to the CLOs? Who finances their business? Who packages those CLOs and works on the underwriting of those and does the hedging for those? Those are still the banks,” said Snare. “So to the extent that the CLOs themselves run into trouble, then the banks will have a correlative balance.”

And for many banks, the leveraged loan space is “a gray area,” said Mix.

“In particular, there isn't really any regulatory guidance or accounting literature that is spot on for the situation that institutions find themselves in,” he said. “It comes down to what's reasonable — whether the bank has a best-practices-level risk management process as it relates to credit.”

What’s more lawmakers have been unable to agree on another round of fiscal stimulus after many of the provisions in the $2.2 trillion Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act expired at the end of July. And Fed officials, including Fed Chair Jerome Powell, have warned that the central bank is limited in its ability to respond to the crisis and have urged more support from Congress.

“If there's no fiscal stimulus, I think there's going to be more defaults for lower-rated companies,” said Gerding. “I think that if there's no fiscal stimulus, there's going to be a lot of pressure if the economy starts to wobble, on the Federal Reserve, to dip lower in their existing facilities or even to potentially create more facilities.”

Powell along with Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin

“I think this is sort of what the Federal Reserve leadership is afraid of,” Gerding said. “They're afraid of no fiscal agreement and are afraid of being put in sort of the recurrent role of rescuer.”

Financial institutions themselves have ample capital and liquidity to be able to absorb defaults, but that only goes so far, said Mix.

“On the private equity side, there's a significant amount of capital, looking for opportunities, and within the banking system, I see significant liquidity as well,” he said. “I think the fiscal stimulus factor is important, however, to ensuring what I view as stability in the system in the near-to-medium term.”