-

After Hurricane Katrina slammed into New Orleans in August 2005, the future for Liberty Bank and Trust Co. appeared uncertain.

February 26 - Alabama

NEW ORLEANS - Gulf Coast bankers reached out to large institutions across the country Thursday, asking for various kinds of help to recover from last summer's hurricanes.

March 3 -

In the two months after Hurricane Katrina, Liberty Bank and Trust Co. in New Orleans lost roughly $40 million of deposits, as customers left town and the steady flow of municipal deposits dried up.

November 3

Liberty Bank and Trust Co. got the wind knocked out of it after Hurricane Katrina decimated the Ninth Ward and the other New Orleans communities its serves.

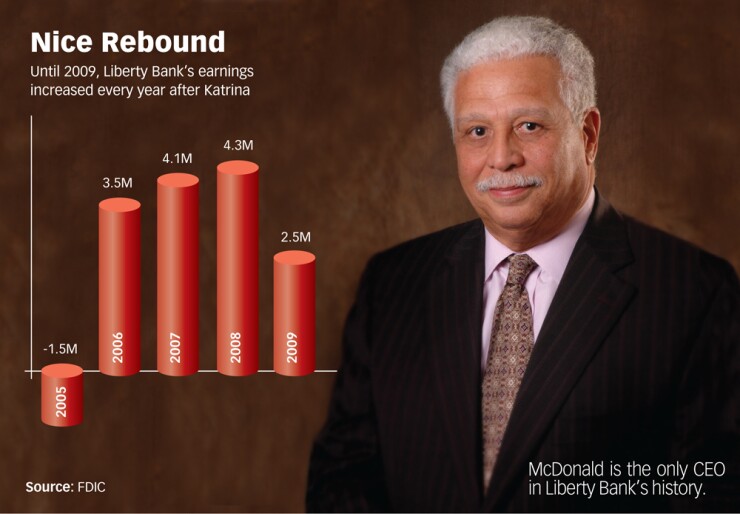

The 2005 hurricane damaged eight of Libertys branches, scattered its customers and employees and wiped out most of its files. In a span of just two months, the minority-focused bank lost 80 percent of its customers and $40 million of its deposits, and for the year it ended up losing $1.5 million.

That Liberty was able to survive that tumultuous year is a credit to its longtime chief executive, Alden J. McDonald Jr. Facing the prospect that many of his customers werent coming back, McDonald developed a certificate of deposit he sold nationwide to investors who were willing to accept below-market rates of 2 percent to 2.5 percent, and used the funds to make nearly $10 million worth of loans in its communities.

McDonald also persuaded several large banking companies to place deposits with Libertyagain, at below-market ratesfor several months to help it get by.

His efforts paid off. In 2006, Liberty posted its highest earnings ever up to that point and McDonald won a spot on Fortune magazines Portraits of Power list.

Still, the catastrophe convinced McDonald and Libertys board of the need to move into new markets. The bank already had branches in Baton Rouge and Jackson, Miss., and a mortgage office in Houston, but McDonald decided to stretch even further from its home base.

We had to deal with the reality that many people who had evacuated New Orleans werent coming back, and so diversifying by expanding into other urban communitiescommunities that we know bestmade the best sense for us, McDonald says.

An opportunity arose in early 2008 when Douglass National Bank, a small African-American-owned bank in Kansas City, Mo., failed, and Liberty emerged as the winning bidder. Then late last year it moved into the Detroit market when it snagged another failed bank, the $21 million-asset Home Federal Bank.

Though Liberty has always focused on urban neighborhoods, McDonald, the only CEO in the banks history, says the Katrina experience strengthened its expertise in community development. McDonalds hope now is that if banks in other urban markets are looking for buyers, theyll think of the $414 million-asset Liberty first. We want to be the premier community development bank in the country, he says.

McDonald, 66, didnt set out to be a banker. In the mid-1960s he was working at the Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans, which at the time helped make rockets for NASA, when he received an invitation to be interviewed at a bank. The invite actually came via his father, who worked as a waiter at house parties and other private functions.

At one event, a couple of guys starting a bank asked my dad if he knew of any black folks who wanted to work in the banking business, McDonald says. I was one of the first African-Americans in the state of Louisiana to enter banking.

McDonald initially worked part time as an auditor and then as a lender for International City Bank and Trust Co., while still keeping his assembly job. But the banking gig worked out well, and he quit his first job after he was offered increasingly important tasks, such as helping to develop one of the countrys first interest checking accounts.

In 1972, Norman Francis, the president of Xavier University, was helping to organize an African-American-owned startup, and recruited McDonald, then just 29, to run it.

I had only been in banking for six years and didnt know whether or not I had enough experience, but he convinced me that I did, McDonald says. Thirty-seven years later and weve been profitable every year, with the exception of five. (Other than 2005, it lost money in 1999, after some early missteps in indirect auto lending. It also was in the red for three years in the 1980s, after the oil market went bust.)

McDonald says a key to successfully running a bank that primarily serves low-income communities is to offset fixed costs with fee income.

A typical customer at a minority-focused bank has one-third the savings of customers at a mainstream community bank, yet the expenses are about the same for both types of banks. While several of Libertys branches are unprofitable, McDonald has kept losses to a minimum by developing new sources of fee revenue, including a service charge imposed on customers who make more than a set number of withdrawals each month.

On the loan side, Michael Grant, the president of the National Bankers Association, a trade group representing minority and women-owned banks, says Liberty largely avoided loan troubles by maintaining strict underwriting standards and devoting significant time and energy to financial education.

McDonald is not going to lose his bank by treating it as a social agency or a welfare operation, Grant says. Those who owe will pay, because hes going to make sure they pay.

McDonald says Libertys lenders typically spend more time obtaining information from prospective borrowers to determine if they are creditworthy. The bank also is flexible on what it will accept for collateral.

We know the community quite well. Most of us grew up poor, so we know the challenges of a person who would typically be turned down at a [mainstream] bank, McDonald says.

Liberty is also among 31 community banks participating in a two-year pilot project with the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. in which it makes small-dollar loans to qualified customers. Liberty offers the loans, ranging from $300 to $1,500, at an 18 percent interest rate and gives customers six weeks to repay. In exchange, borrowers must agree to take a financial literacy class and put 9 percent of the amount of the loan into a Liberty savings account. To cover the programs costs, Liberty charges $10 per application and another $15 for its financial literacy classes.

We receive more late fees than most banks because of the frequency of lending money, but its still better than the customer going to a payday lender, McDonald says.

Sherwood Woody Briggs, managing director at Chaffe & Associates Inc., says that McDonalds skills as a banker were on full display after Hurricane Katrina, which disproportionately affected the neighborhoods Liberty serves.

Still, Briggs says that, over the long term, perhaps the greatest challenge Liberty and other minority-owned banks face is competing against mainstream banks that have larger lending limits and more sophisticated products. These banks tend to poach Libertys customers as they move up the income ladder or as their businesses grow.

Alden is always mindful that some loan officer, particularly a black loan officer, from Chase calls one of his customers who is now doing $20 million a year in business, and says, 'We can take care of you, give you more complicated services like an international letter of credit, trust and private banking, and the next thing you know this guy is gone, Briggs says. Thats the toughest challenge.

Of course, the best way to offset the loss of customers is to bring in new ones.

Besides the two failed banks, Liberty also acquired the $25 million-asset United Bank and Trust Co. in New Orleans last year. Today, Liberty has 24 offices in six states, and McDonald says it has the capacity to more than double its size.

His vision is for Liberty to have a presence within the urban core of many of the countrys major cities, including the possibility of buying or chartering a bank in Los Angeles. McDonald is also looking to expand into smaller communities that have a concentration of minorities and develop banking relationships with state and local governments. He continues to search for opportunities to invest in nonprofits that focus on community development too.

If we feel we can go in and bring a bank back to life, well move on that opportunity, he says. We can do well helping to revitalize urban communities.