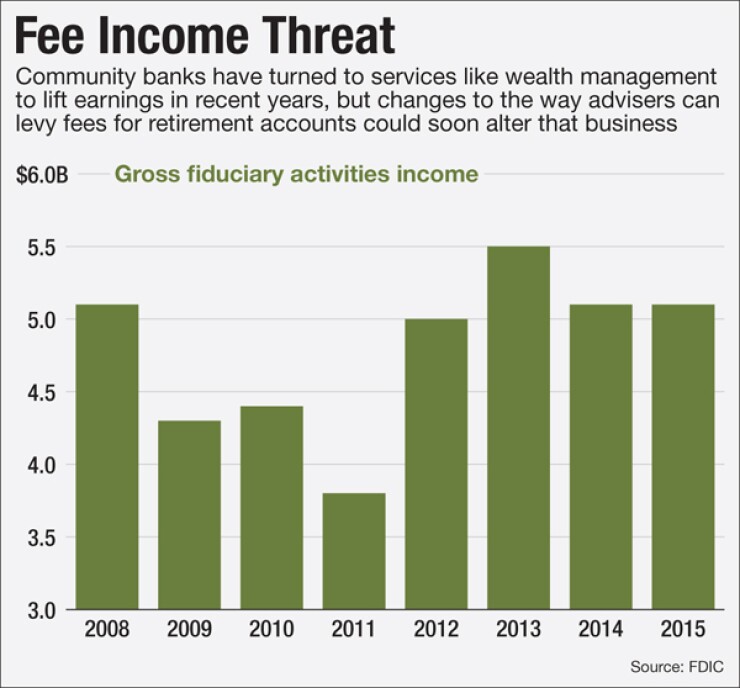

Wealth management units have been a surefire source of fees for banks over the last few years, as low rates dragged down spread income. But a policy change will likely be a crucial test to the business model.

The Obama administration on Wednesday unveiled new rules that will change the way firms provide advice on retirement investments. The rule changes the way financial advisers charge fees — including, in most cases, prohibiting commissions.

The fiduciary rule comes as banks face broad-scale declines in advisory fees, following a tumultuous few months for the stock market. The timing of policy change makes one thing clear: Wealth management — and the money that business contributes to the bottom line of banks — is set to face significant challenges.

-

The financial industry and the White House are gearing up for a fresh battle this spring over investment advice for retirement savings.

April 30 -

A top official with the Labor Department defended the controversial plan to expand the definition of "fiduciary" to cover people providing advice to retirement plans on a commission-based model, a proposal strongly opposed by industry groups representing independent broker-dealers and advisors.

October 5 -

With the Department of Labor poised to toughen rules for consultants and advisers to retirement plans, industry practices are under a new spotlight.

December 1

Nonetheless, the details released early Wednesday suggest that Obama administration officials want to assuage industry concerns about the workability of the rule and potentially avert court fights, while still enacting a higher standard of duty to clients.

"With the finalization of this rule, we are putting in place a fundamental principle of consumer protection, that a consumer's best interest must come before a financial advisers' best interest," Secretary of Labor Thomas Perez said.

The timeline to implement the rule was extended to one year from eight months in the amended version. Firms will need to be in full compliance by Jan. 1, 2018. Industry trade groups such as SIFMA

The best-interest contract exemption has been changed significantly. The Labor Department now says clients will have to sign such a contract when they open accounts, not when they first meet a broker or adviser. The exemption was the subject of intense industry scrutiny, with CEOs and industry trade groups sharply criticizing it, saying it would be unworkable in practice.

Perez said the department made these and other changes after receiving feedback from industry groups and consumer groups. "We listened, we learned and we adjusted," he said.

The final version of the rule also does not penalize proprietary products, such as complex annuities.

"Proprietary products are certainly permissible products that have an important place in the market. The key is … you have an obligation to put your clients' best interests first," Perez said.

Also of core importance to wealth management firms: They'll be able to notify existing clients of the changes to the firm's obligations by email, Perez said.

'IT'S NOW THE LAW'

The amended version is scheduled to be published today, ending several years of contentious debate that included intense industry lobbying and several failed attempts by Republicans in Congress to derail the effort to craft a new standard governing retirement advice.

The fierce back-and-forth between opponents and advocates was due in no small part to the dramatic effects the rule could have on those whose income depends on advising Americans on their retirement assets – more than $22 trillion, according to Cerulli Associates.

Privately, executives have said the complexity of the rule will make it difficult to develop new compliance policies and procedures, particularly for larger firms that have more than 10,000 advisers. And while changes made by the Labor Department may go a long way to easing the industry's acceptance of the rule, all wealth managers, financial advisers and financial planners will now be held to a new, higher standard when providing retirement advice.

Until now, advisers have been operating "in a structurally flawed system. The interest of the consumer is all too often not aligned with that of the firm and the adviser," Perez said.

For example, firms' marketing materials, often tout that the client comes first. "With this rule," Perez said, "we are making sure that that is no longer is just a marketing slogan. It's now the law."

When the White House announced its latest proposal for a fiduciary standard last year (its first initiative was rolled out in 2010, then shelved amid the firestorm of opposition), it pointed to a study suggesting that Americans' retirement savings were at risk due to bad advice; Americans lose about $17 billion in retirement savings per year due to conflicted advice, according to the White House Council of Economic Advisors. Insiders say that the Obama administration sees the rule as a key part of the president's legacy.

The Labor Department has regulatory oversight of retirement advice under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act, passed in 1974 at a time when pensions accounted for a much larger portion of Americans' retirement assets and 401(k) plans did not yet exist.

But even some supporters for a higher standard called into question whether it was ideal to have the Labor Department lead on this matter, noting the limits to their regulatory powers. Other kinds of financial advice would not be covered by this rule.

A LONG BATTLE

The Labor Department's efforts have stood in contrast to that of the SEC, which has been authorized to craft a fiduciary rule since the Dodd-Frank Act passed in 2010. SEC Chairwoman Mary Jo White has repeatedly said that such a rule was a top priority for the commission but that it was a complicated undertaking. Critics,

Much of the debate at the hearings about the Labor Department proposal centered on commissions, and whether or how brokers' incentives could be at odds with their clients' best interests. While critics said that the rule would effectively and unfairly ban commissions,

The agency received more than 3,000 letters

The debate appeared to reach a fever pitch last August during several days of public hearings,

"It is hard enough to save for retirement. Conflicted investment advice should not be one of the barriers millions of Americans face as they work to save for their retirement," David Certner, legislative policy counsel for AARP, said on the first day of the hearings.

Kristin Broughton contributed to this article.