JPMorgan's Chase Private Client group used false evidence to get rid of an advisor.

This is how the firm tried to make sure no one knew.

By Ann Marsh

The musty smell from an indoor pool hung in the air as Umbreen Kazmi took a seat at a small folding table in the nearly empty ballroom of a Phoenix airport hotel. The table served as a makeshift witness stand from which the JPMorgan Chase compliance manager faced three arbitrators hired by one of the country's top regulators, the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority. The bank’s lawyers sat at their own row of tables to her left, facing opposing counsel for a once-successful JPMorgan advisor, Johnny Burris.

Neither Burris, who had become a whistleblower against his former employer, nor Kazmi, one of Burris’ former managers, likely imagined their careers taking them to such a setting when they went to work for one of the largest and most prestigious banks in the world.

The hotel they were in, a Crowne Plaza, was next to a noisy interstate, but it wasn’t the sound of traffic that made it hard to hear. Clattering pans and loud voices from the adjacent hotel kitchen disrupted the summer 2014 arbitration, which stretched over eight days.

“We would appreciate it if you could think about speaking a little louder," the lead arbitrator, Robert McConnell, requested of Kazmi as she began.

The purpose of her testimony was to address Burris’ claims that he was wrongfully terminated and then defamed in retaliation for refusing to invest more of his clients’ savings in the bank's high-priced, in-house funds and managed accounts. The hearing, like many private arbitrations, favored the employer over the employee: Burris wasn't allowed to call some JPMorgan witnesses he wanted his lawyer to question, and the bank — with the approval of FINRA, the arbitration’s overseer — refused many of his discovery requests. Much of the discovery he did receive was redacted.

In the chlorinated air, over the kitchen noise, Burris' lawyer, Nicholas Woodfield, began a line of questioning aimed at a central issue: Were clients’ letters of complaint against Burris genuine?

"OK, if you would turn to 178," Woodfield instructed Kazmi, according to a previously confidential transcript of the arbitration obtained by Financial Planning. "Who is this person? William what?"

"William White," Kazmi said, incorrectly stating the name of one of Burris' former clients, William Wiley. "I can't remember the exact spelling of the name, but William. He also had written a letter." She couldn’t remember when, but repeated, "He wrote a letter." Woodfield turned to a letter from another former client, Carolyn Scott.

"Was this written by someone at JPMorgan?" he asked Kazmi.

"Absolutely not," she replied.

The deception

In fact, another JPMorgan manager had written the letter, using Scott’s name, and another letter using Wiley's, as well as a third. None were actually written by Burris’ clients.

Both Scott and Wiley later signed affidavits attesting they had never filed complaints. Wiley's affidavit said he and his wife were concerned about a problem caused by their tax preparer, not Burris. Scott said she didn’t even understand the letter the bank wrote over her name, with its use of terms like "nonqualified," "qualified" and "in-kind.”

"There should never have been a complaint against Mr. Burris," Scott wrote. Contacted by Financial Planning, she added: "I never had a problem with Johnny.”

As the arbitration wore on, JPMorgan brought in a higher-ranking executive who backed Kazmi’s account. Phil Haigis, who now works for JPMorgan in Columbus, Ohio, took the same makeshift witness stand to address how bank managers handle aggrieved clients.

"We, as principals, do not help a client write a complaint," Haigis told Woodfield.

"That wouldn't be something that normally happens?" Woodfield asked.

"Nowhere in the industry," Haigis responded, just as unequivocally as Kazmi.

Bank representatives said the allegations of manufactured evidence were a distraction from the true concern: Burris himself.

Starting out as a bank teller, Burris worked his way up in the industry to become a top performer in JPMorgan's private bank. The son of a white mother from West Virginia coal country and a father adopted from Korea, Burris was raised by his stepfather and grandparents. Burris is a lifelong hunter, proud of his ability to track, kill and dress bear and mule deer meat in the wild. His unblinking expression and penchant for making blunt statements can be unnerving.

"I cannot lose this case," Burris texted another of his former managers, Deborah Valenzuela, in advance of the arbitration, she told the panel. "Now is your time to set things right."

That message, combined with a gun silencer permit Valenzuela told arbitrators she found in a cabinet at his desk after he was fired, left her feeling "kind of freaked out. … I was worried about retribution, to be honest," Valenzuela said.

Burris says he owns a “suppressor” — his preferred term — because he has tinnitus from hunting without ear protection. JPMorgan introduced details about his hobby into the arbitration to portray him as potentially dangerous, he says. It’s also why, Burris’ lawyer told the arbitrators, FINRA hired two armed security agents to screen everyone with a metal detector. JPMorgan is "trying to make Mr. Burris such a bad person … that you don't even think about what the real claims are," Woodfield said. Several arbitration lawyers not involved with the case called the security measures highly unusual for a FINRA hearing.

In his opening remarks, JPMorgan lawyer Michael Ungar sought to counter any positive impression the arbitrators may have had of Burris. "At first-blush outward appearance, he seems like a likable and friendly fellow," Ungar said. "But he lives in an alternate universe. He really does. In that alternate universe, where he lives, theories and conspiracies abound, and things like truth, facts and realities, those don't matter,” Ungar said, claiming Burris was “a one-man monsoon" out to destroy the reputations of his managers.

Indeed, he was a “supervisory nightmare,” Ungar added. "That … is the real motivation behind Johnny Burris' termination. As you know now, it had nothing to do with stealing his book of business or his refusal to offer managed investment products. … Mr. Burris' entire case is really nothing more than an empty lawsuit desperately in search of some facts."

The arbitrators agreed. They dismissed Burris’ case, denying his claim for $7 million in damages, among details that have been reported previously. But Financial Planning has obtained additional documents not disclosed previously that demonstrate JPMorgan was aware Kazmi provided arbitrators with false evidence. Moreover, they show the bank knew this before the arbitrators returned their decision.

These documents show that, days after the arbitration wrapped up but a week before the panel released its decision, the certainty Kazmi displayed about the authenticity of the letters from clients had evaporated.

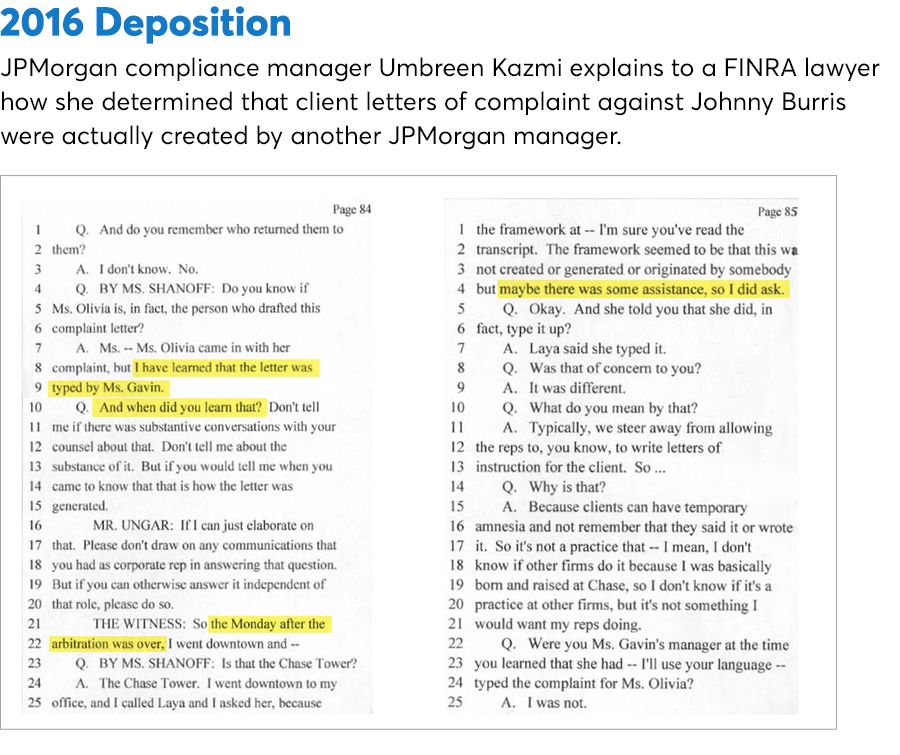

“Maybe there was some assistance" from the bank in writing the complaints, Kazmi conceded, without explaining what had led her to doubt the account she gave to arbitrators days before, according to a transcript of a deposition she later gave to a FINRA enforcement officer.

From her office in the Chase Tower in downtown Phoenix, a short walk from Chase Field, home of the Arizona Diamondbacks, Kazmi decided to reach out to another of Burris' former managers, Laya Gavin.

"I called Laya and I asked her because the framework … ," Kazmi told FINRA attorney Margery Shanoff, repeating herself, "the framework seemed to be that this was not created or generated or originated by somebody." Kazmi didn't explain what she meant by "framework," so Shanoff got to the point: "She told you that she did, in fact, type it up?"

"Laya said she typed it," Kazmi said.

To view larger, click here.

To view larger, click here.

Meanwhile, the bank’s lawyers did not tell the arbitrators that JPMorgan was near the end of a five-year SEC investigation in which it would eventually admit breaching its fiduciary duty to clients nationwide for actions similar to those Burris accused it of committing. As a result of that investigation, JPMorgan paid the SEC's highest fine of 2015, $267 million, plus $40 million more to another regulator, bringing its total penalties to $307 million — substantially greater than the initial $185 million fine Wells Fargo paid a year later for the more widespread scandal of opening millions of unauthorized customer accounts.

Yet despite this finding and despite knowing that the bank had given false evidence in the arbitration, FINRA still proceeded with a subsequent disciplinary case against Burris. That makes Burris, a whistleblower who protested fiduciary breaches against clients, the only JPMorgan employee punished publicly in connection with this case.

Behind-the-scenes details and previously confidential records that both the bank and FINRA sought to keep from public scrutiny paint a bleak picture of the consequences for a financial advisor who resisted pressure to sell investments he did not deem suitable for his clients. The portrait of the agencies whose stated mission is to protect the investing public is arguably bleaker.

The SEC would not discuss the case. FINRA issued a statement: “FINRA routinely works closely with whistleblowers to pursue misconduct, encourages them to utilize our whistleblower tip-line and supports strong protections for them. We also support high standards of conduct for all brokers and we are obligated to take appropriately tailored action when FINRA’s independent investigation reveals that a broker violated basic FINRA rules.” A spokeswoman declined to address how its handling of the Burris case comports with its commitment to protect whistleblowers.

Told of the revelations in the case, JPMorgan spokeswoman Patricia Wexler would say only: "We will decline comment on this."

The bank, however, did elaborate in a court filing, in response to a pending lawsuit brought by Burris in federal court in Phoenix. It denies almost all of his accusations, including claims that it misled arbitrators and had been "pushing" or "steering" clients into its own higher-cost investments. The bank also said it fired Burris for "legitimate [and] nonretaliatory business reasons." However, Burris says a compliance officer approved the actions that the firm says required his termination.

Among the bank managers at the arbitration, Kazmi and Haigis did not respond to multiple attempts to reach them. A JPMorgan lawyer, Matthew C. Crowl, instructed Financial Planning via email: "Do not contact Ms. Kazmi directly."

For her role in creating evidence, FINRA decided on modest punishment for Gavin: A private letter of caution, which had remained confidential until Financial Planning learned it had been included in an unrelated filing and received it from the state of Arizona in an open records request.

The letter of caution states: "You misled the firm as to the provenance of the complaint letters, creating the impression that the customers drafted the complaint letters themselves when they had not," Eric Brooks, a senior director of FINRA's enforcement department, wrote to Gavin two years ago. The regulator disclosed no penalties. Gavin, who did not testify at the arbitration, declined to comment.

There's no record of any punishment for Kazmi. "If the self-regulator is not going to discipline a compliance manager for making false statements under oath, then why do they exist?" Burris asks.

The Burris case raises troubling questions for the industry and the investing public:

How can FINRA act as a neutral arbiter of industry disputes when it is controlled by the financial services powerhouses it is meant to oversee?

What influence did JPMorgan — whose former top lawyer, Stephen Cutler, sat on FINRA's board during much of this conflict — wield over the regulator?

How can a financial advisor whose career is wrecked by false evidence find justice?

Two U.S. senators, Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) and Tammy Baldwin (D-Wisconsin), expressed concern about Burris’ plight to FINRA CEO Robert Cook after the lawmakers were contacted by Financial Planning about the Burris case. Cook met with Baldwin on Capitol Hill in December to discuss the issues raised, according to sources familiar with the meeting. (Senate aides would not discuss what transpired; FINRA would not acknowledge the meeting took place.) “I would hope that any whistleblower would be given a fair hearing in the first place and, if new evidence or information comes about, they’d be given an opportunity to present it and defend their name,” says Grassley, who along with Baldwin was a co-founder of the Senate Whistleblower Protection Caucus.

The SEC’s former whistleblower chief, Sean McKessy, says FINRA should reconsider the arbitration finding and a subsequent action it took against Burris. “Common sense and common decency suggest that if someone has a black mark against their record and is ultimately vindicated, it doesn’t seem fair to not take a second look.”

New 'complaint'

Two years after the arbitration loss, Burris was considering his legal options and trying to resurrect his shattered career as an independent advisor. Yet FINRA was coming at him with evidence of a new client complaint, which also originated after his termination. The case followed a familiar pattern: The supposedly aggrieved party disavowed the complaint.

"We were never displeased with Mr. Burris. Frankly, it was just the opposite," the couple, Leona and Raymond Weaklend, wrote in an affidavit. They also sent an exasperated, notarized letter to Shanoff, the FINRA enforcement attorney, that concludes, "I hope this ends our involvement. If not, maybe Chase needs to reimburse us for the stress, time, frustration and wrongful statements attributed to us by Mr. [Andrew] Held," another of Burris’ former managers.

Shanoff — who had taken the deposition from Kazmi that uncovered the manufactured evidence used in the Phoenix arbitration and had filed the Weaklend case against Burris herself — did not respond to requests for comment. Held, whose LinkedIn profile says he’s now an advisor with JPMorgan’s private bank in the Seattle area, declined to comment.

Despite the Weaklends’ insistence that they had not filed a complaint, Burris, burdened by years of legal bills, opted to settle that FINRA case, noting as well that he was dubious he'd get a fair hearing given that JPMorgan's former top lawyer was on the board of FINRA.

'If I had to do it over again, would I? Yes, without a question.'

His frustration mounted after FINRA failed to drop its regulatory case against him, even though, three months earlier, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (which administers the whistleblower protection program for financial services employees) finally weighed in, following several investigations by Financial Planning. It found JPMorgan had retaliated against Burris over his whistleblowing, “blacklisted” him in the industry and caused him "reputational harm” by posting client complaints to his publicly available FINRA BrokerCheck record. But OSHA awarded Burris just $164,000, as well as a bonus of $60,000 and payment of about $250,000 in legal fees — far less than the millions he believes the bank owes him. And although the agency instructed JPMorgan to have Burris’ BrokerCheck record cleared, the falsified complaints JPMorgan used as evidence remain.

FINRA blocked attempts by Financial Planning to learn from the arbitrators if revelations about the false evidence, and JPMorgan's admission of wrongdoing nationwide, would have influenced their decision. Reached by phone last year, McConnell, the chairman of the arbitration panel, said he could not discuss the case.

"As a matter of fact," he said, "I received a phone call from FINRA a couple of days ago, telling me that somebody like you likely would be calling me and reminded me of my obligations, which involve not talking to you."

During the proceedings, arbitrator Katherine Harmeyer had voiced concern about the reputation of Haigis, one of Burris’ former managers. Burris had secretly taped Haigis as well as Held pressuring him to sell in-house investments, a recording of which was later published by Financial Planning and The New York Times.

Product pushing: Andrew Held and Johnny Burris

“I can see a situation in which Mr. Haigis presumably could be harmed if there are in fact selected portions of this available on the Internet,” Harmeyer said. “Should he ever unfortunately choose to leave Chase, then it might become an issue with a future employer.”

“I very much appreciate the comments,” Ungar, the bank’s lawyer, said during this segment. “You are stealing a bit of my thunder in terms of my closing argument.”

A review of nearly 20 years of the combined voting records of arbitrators McConnell, Harmeyer and Brian Evans, a compliance manager at Edward Jones, shows they have overwhelmingly favored financial firms. In 20 comparable disputes they arbitrated between firms and advisors, they found in an advisor’s favor just five times.

Pro-industry track records are common among long-serving FINRA arbitrators, according to securities law expert and FINRA arbitrator Doug Schulz, who worked briefly on Burris' case.

"They know that, if they rule against the brokerage firms, they [can] get stricken" from future cases, Schulz says, “so what they do is either they rule for the brokerage or they give such watered-down damages that the industry doesn't strike them."

Who's accountable?

Four years after JPMorgan admitted to harming clients nationwide, Burris continues to ask why FINRA, the SEC and other regulators have not taken any public action against the bank's executives. To him, a recurring theme is that, while he lost his job over complaints disavowed by his clients, Jamie Dimon remains as CEO, despite the company's regulatory settlements following nationwide breaches of fiduciary duty to clients, the type of which Burris had resisted. Dimon also has three criminal disclosures on his BrokerCheck listing. One was posted in 2014, the day after it was announced the bank agreed to pay $1.7 billion to avoid prosecution for serving as Bernie Madoff's banker for decades. Another followed JPMorgan's 2015 guilty plea for rigging foreign currency exchanges. A related disclosure in 2016 remains on Dimon's BrokerCheck record as a "pending charge,” although the bank persuaded a French court to dismiss a criminal finding that it helped clients evade taxes.

Each of the criminal disclosures includes this statement: “Mr. Dimon is disclosing this matter because, in certain respects unrelated to the underlying conduct, he may be deemed to have exercised control over JPMC. There are no allegations or facts set forth in the information or plea agreement that refer to Mr. Dimon personally.”

Among the CEOs of the nation's top banks and broker-dealers, Dimon is the only one with criminal disclosures on a BrokerCheck report. A representative for Dimon declined to comment.

Will managers or executives be penalized?

In addition to revisiting its disciplinary finding against Burris, McKessy, the former SEC whistleblower chief, thinks FINRA and other regulators should punish top executives who’ve presided over scandals. “I’m a big believer in the power of shame,” he says.

As Maria Elena “Mel” Lagomasino — a former JPMorgan private banking chief who now runs her own independent advisory firm — sees it, "We give them a little slap on the wrist, and then they pay a fine that is insignificant given their size and scale, and then they go back to what they are doing. ... People call it the wealth management industry. I call it the wealth extraction industry," adds Lagomasino, who left the bank after watching what she describes as the erosion of JPMorgan's fiduciary culture. “Over the last generation, there's been a tremendous transfer of wealth from investors to financial services companies and to financial executives."

A former JPMorgan advisor who joined the office Burris used to work in four years after he was fired, says product pushing is ongoing. Ricardo Peters says the bank fired him for raising the same concerns, and he makes the allegation in his own whistleblower complaint, filed with OSHA last year.

For Burris, the fight continues: He awaits the federal trial, expected to begin later next spring. A recent court filing by the bank includes an acknowledgement that retaliation against Burris may have taken place: "To the extent [Burris] suffered any retaliation, such retaliation was conducted by someone acting outside of the scope of their employment and, despite reasonable supervision, defendants were unaware of any such retaliation."

Editor: Scott Wenger. Designer: Paola Palacios. Main photo: Scott Wenger.

Feeling betrayed: 'How many other retirees has this happened to?'

A year after JPMorgan fired him, Burris walked up the bone-colored driveway of the home of a former client at the bank. The 78-year-old retiree lived in a kind of house ubiquitous in the Sunbelt, with a sharply gabled roof covered in pale red tiles, a tan stucco exterior and low-water landscaping. The man had called Burris hoping he’d take a look at changes to his account.

During his two and a half years as a JPMorgan advisor in Sun City West, Arizona, Burris had thrived, building his book of business to $90 million in assets under management.

"I have had the privilege of representing many financial advisors, managers and the firms, some of the largest firms in the United States during my nearly 30 years of practicing law, and I must tell you that Johnny Burris was a star, the likes of which we rarely see when it comes to the sales production side," Michael Ungar, the bank's lawyer, had told the arbitrators during Burris' wrongful termination hearing.

Despite the glowing review, arbitration transcripts show Burris put only $16 million of that $90 million into the bank’s managed accounts and some of its proprietary products, which both generate high fees for the firm. The low percentage, 18%, was a problem for the firm, which generally wanted that level at 60%, he says. Had Burris put clients' money in those managed accounts, he estimates he could have added $100,000 to $150,000 to his annual income of about $300,000. But he says it would have been wrong.

"I wouldn't put my clients in anything I wouldn't put my grandparents in," says Burris, who was raised mainly by his paternal grandparents and whose client base has always been dominated by retirees.

In the home of his former client, whose family requested his name not be used, Burris sat at the kitchen table, which looked out at a golf course. Handing over his account statements, Burris says the man told him, "This doesn't look right."

While a client of Burris, the man had purchased more than $200,000 of Class A shares of seven Franklin Templeton mutual funds for which he paid $9,887 in commissions, of which the bank collected 65% and Burris got 35%. The client intended to hold them indefinitely, Burris says. (Burris was compensated by commission and bonus.)

After Burris was fired, Laya Gavin, the former compliance manager who acknowledged creating the evidence of client complaints used against Burris, took over the retiree's account, along with Burris' entire book of business. Perusing the man’s statements, Burris saw she had sold his funds, reinvested in JPMorgan's funds and put him in a bank-managed account, which meant the bank could levy an annual management fee of 1.6%, or $3,504.

The man learned about the changes after the fact, Burris says. "One last form!" Gavin wrote in a handwritten note to the retiree, asking him to belatedly approve the reallocation. "If you can sign, date and either drop off or UPS back, thank you!" The note is included as evidence in a complaint the retiree filed with FINRA, according to documents obtained by Financial Planning.

"I would never [have] opened an account with a recurring annual fee of $3,504. Especially when I had recently purchased the Class A shares," the man said in the complaint. "If this has happened to me, how many other retirees has this happened to?"

That wasn’t all: Gavin constructed a portfolio invested 75% in equities, including hedge funds. That "shows a complete disregard for retirees who depend on a retirement account to help them supplement their income,” Burris says. “Anybody who has any common sense wouldn't put somebody of [his] age into a growth model."

The changes Gavin made in the man’s account are similar to the fiduciary violations the bank admitted to in the 2015 SEC settlement and related regulatory cases. JPMorgan "breached its fiduciary duty to certain clients," an SEC statement said, "when it did not inform them that they were being invested in a more expensive share class of proprietary mutual funds, and JPMCB did not disclose that it preferred third-party-managed hedge funds that made payments to a J.P. Morgan affiliate."

Sitting at his former client’s kitchen table, Burris recalls the man growing livid when he explained what had happened. Although the portfolio changes weren’t his doing, the man felt ashamed, Burris recalls. “When you put your trust in someone and they betray your trust, … it changes your perspective on things," he says.

To settle the FINRA case the former client filed, JPMorgan offered to reverse the sale of the Franklin funds, so long as he filed a confidentiality agreement, according to a letter from the bank. Instead, the man moved his money elsewhere after a market rally, Burris says.

The man died in 2017.

On Gavin’s BrokerCheck report, there is a single customer dispute for the same amount, $5,000, that the retiree had requested in damages. The disclosure concludes: "Closed — No Action."

The former client’s experience was hardly unique, Burris believes, as demonstrated by the cases brought by the SEC and other regulators.

JPMorgan took 65% of the former client’s $3,504 management fee, or $2,278, while the advisor — in this case, Gavin — got the balance, he says. Given that Burris had more than 1,100 clients with an average account size of $100,000, JPMorgan's average income for each would be about $1,040, enough to generate more than $1.14 million in additional revenue annually for the bank just from his book of business.

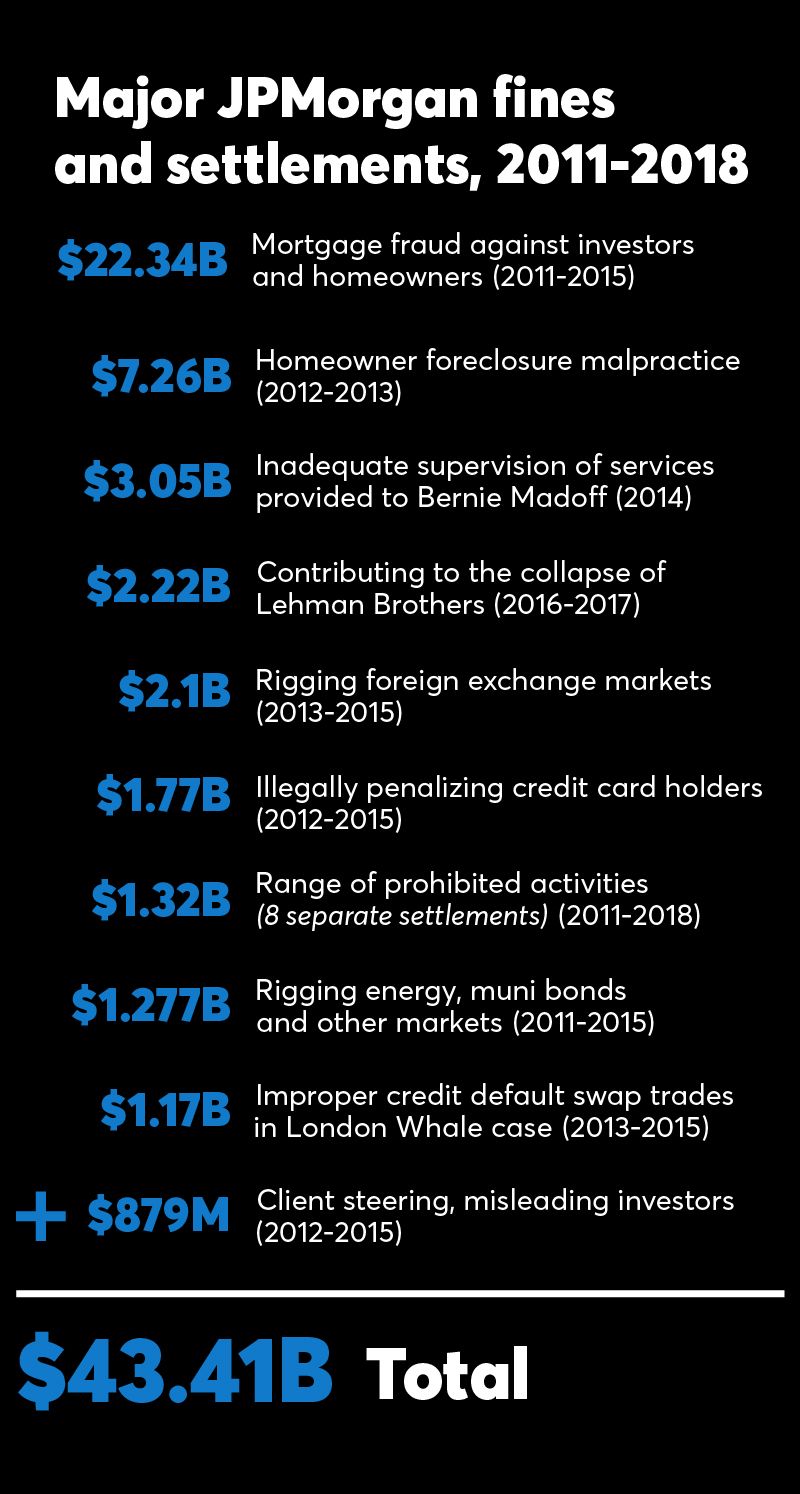

"Multiply that number by 3,000 licensed reps around the nation and you get $3.4 billion," says Burris, rounding up from the 2,877 advisors the firm cited in its first-quarter report. Following allegations of wrongdoing, "That's why Jamie Dimon tells Elizabeth Warren, 'Go ahead and hit us with a fine,' " Burris says, referring to a 2013 meeting the Massachusetts senator now running for the Democratic presidential nomination, recounted having with JPMorgan's CEO in one of her books. Since 2011, JPMorgan has paid nearly $43.41 billion in fines and settlements, according to research by Financial Planning and the House Financial Services Committee, which used data from investment banking firm Keefe Bruyette & Woods.

"Do a cost analysis," Burris says, arguing that it makes sense for JPMorgan to keep paying fines. "Nobody personally pays a price." —Ann Marsh