JPMorgan Chase is allowing so-called ethical hackers to probe its websites for soft spots, making it one of a limited number of banks to employ a cybersecurity practice common among startups.

JPMorgan declined to say whether the glitch-finding initiative — known as the "JPMorgan Chase Responsible Disclosure Program" and

However, it did say that anyone who finds a security flaw will not face any legal repercussions, as long as they do not exploit the flaw to commit fraud or steal customer information.

The bank's effort has all the earmarks of a typical bug bounty program, where security researchers can get recognition or compensation for finding and reporting vulnerabilities or errors on corporate websites and systems.

For their efforts, researchers who make substantial contributions on finding flaws for JPMorgan can see their name on a leader board or touted in media, according to the disclosure program's online link.

The program illustrates how crowdsourced cybersecurity — a tactic that some industry analysts say has the potential to be exploited — has begun making inroads into banking.

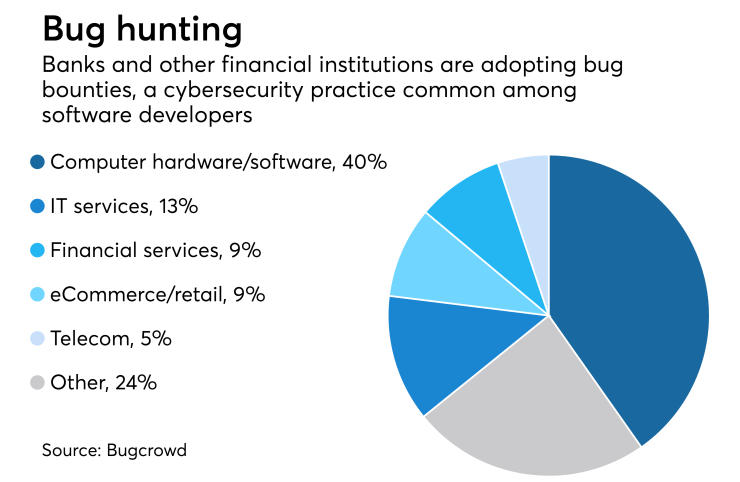

There has been an increase in the adoption of bug bounty programs in financial services, but it is still relatively small, according to Bugcrowd, a cybersecurity firm that employs hackers to find flaws in corporate website defenses. Most programs are kept quiet, but some financial firms such as Mastercard, Square and ING make the existence of their programs public.

Such programs are common in other parts of the business world but less widespread in banking, said Scott Ramsey, managing principal at Capco.

“Large banks that have in-house development programs are not open to the idea of making apps available to ethical hackers for them to try and identify vulnerabilities and exposures in the app," Ramsey said.

There are several reasons why, Ramsey said, but an obvious one is that despite the best intent of such efforts, companies are still dealing with the unknown.

"One can never really be sure of the identity of the ethical hacker," he said. "It could be a black-hat hacker or it could be a competitor. Exposing the app could eventually provide the black hat with the opportunity to find an obscure vulnerability, not report it in hopes that no one else identifies it and use it later for illicit gains.

"A black hat could potentially obtain enough of an insight on app structures that they could use that information to develop an attack vector to exploit systems for illicit gains.”

At SourceMedia's RegTech 2018 conference in New York, panelists in a crowdsourced security discussion were positive about the benefits of bug bounty programs — but there were caveats.

“You’re dealing with a community whose sole purpose is to push and bend rules as much they can,” Nick Selby, director of cyberintelligence and investigations at the New York Police Department, told the audience. “Most people who do this are motivated to establish themselves, do some good, and make some money,” he added.

Amit Elazari, a cybersecurity lecturer at the University of California, Berkeley, said financial services firms must have a clearly crafted guidance that details what researchers can and cannot do in a bug bounty program.

“When I see a bug bounty with no technical scope, it signals to me you have not done your due diligence,” she said. “It’s a form of negligence. I think [researchers] provide incredible value, but make sure the rules of the game are enforced.”

Selby shared an anecdote to illustrate the point.

A hacker contacted him and his team and said there was an unsecured vulnerability in a computer system, and the hacker wanted money for making the discovery. Selby thanked the hacker and said it was outside the scope of work, and the hacker just went away.

“It’s really difficult,” Selby said, “to find that fine line between bug bounty and extortion.”