-

The Obama Administration, including the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and Department of Education, unveiled initiatives this week aimed at bringing transparency to the student lending market and making repayment easier for recent college graduates.

October 26

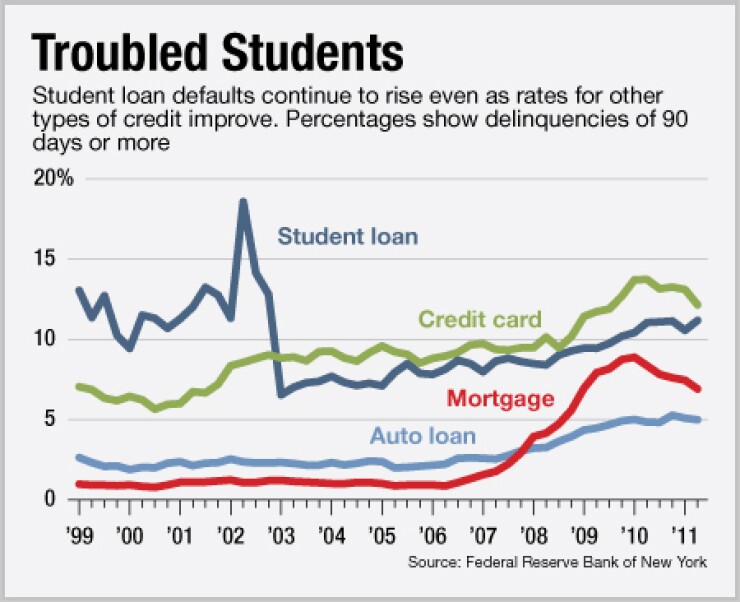

Policymakers who stood by and watched the mortgage bubble inflate, and then explode, ought to pay attention to what's happening in the student loan market.

The parallels may not be precise, but they are pretty darn scary.

As with mortgages, the student loan market is growing rapidly, delinquencies are jumping and the federal government is playing an outsized role.

And just as buying a home was considered evidence of achieving the American dream, becoming a college graduate is viewed as a ticket to prosperity.

But millions of people made tragic mistakes in buying homes they couldn't afford, and tens of thousands of students are realizing they are trapped by the debt they took on to finance their educations.

Total outstanding student debt is nearing $1 trillion and may for the first time outstrip credit card debt when third-quarter data is released later this month.

The Department of Education said the default rate on student loans rose to 8.8% from 7% last year. But the way the government calculates this figure guarantees it's being lowballed.

The department bases its default figures on the group of student borrowers who have been out of school for just two years. Deferments are routine and can push off a graduate's first repayment check for as much as a year. That tends to underestimate the default rate so, starting next year, the department will shift its default calculation to count students who have been out of school for three years. This is expected to drive the default rate higher.

The housing crisis — whomever you blame for it — was caused by people buying homes they could not afford. That's exactly what's happening in education. Students are getting loans to pay for educations they can't afford. Again, put the blame where you like — skyrocketing tuition, generous credit terms, lousy underwriting — but the reality remains.

To be sure, even at $1 trillion the student loan market is just a sliver of the $8.5 trillion mortgage market. But that doesn't give policymakers a pass to ignore what's happening.

And President Obama isn't ignoring it. He's arguably making it worse by tinkering around the edges rather than addressing the fundamental problem — the soaring cost of tuition.

According to the administration, for the past decade tuition and fees at public colleges have been increasing nearly 6% a year faster than the rate of inflation.

The Department of Education said two-thirds of the graduates of four-year institutions have student loans. For those at public institutions, the average debt was $20,200, that's up 20% since 2004. The statistics are worse for graduates of private schools — $27,650 in debt, up 29% since 2004.

Of course, repaying a loan is a whole lot easier when you are earning a paycheck. But that's the rub. With the employment rate at 9%, even young people with prestigious degrees can't find a job. Some of them have joined the "Occupy" protests in cities around the country, which is getting politicians' attention.

Indeed, students were a solid slice of President Obama's base in the 2008 election and there is no doubt he'd like to count on them for his 2012 re-election.

In late October, the president announced he is moving up by two years a plan that will reduce the maximum required payment on student loans to 10% of annual discretionary income from 15%. Debt not repaid after 20 years will be forgiven.

This is all happening in the wake of the government taking control of the student loan market.

As of July 2010, the federal government stopped guaranteeing student loans made by private-sector lenders. The rationale was this would save the government money. But since then the private market for these loans has shriveled. Of the $118 billion in student loans made this year, just $8 billion will be by private-sector lenders.

The government's dominance may be part of the problem.

Would the cost of a college education be rising this quickly if students did not have easy access to government loans? Credit for every other type of loan has declined since the crisis so it's likely the student loan market would be a lot tighter if banks were still in the business.

Obviously education is important, both for individuals and the country as a whole. But just as borrowers are walking away from homes worth less than their mortgage, what's to stop graduates from defaulting on their student loans?

Harrison M. Wadsworth 3rd, a principal with Washington Partners who advises the Consumer Bankers Association on student loan issues, says the current path is unsustainable.

"The government and the higher ed community have got to take another look at how we are financing education in this country and look at the harder policy questions: Is an expensive college education one everybody needs or are there other kinds of training programs that are cheaper and are going to yield a better result for many people?," he said. "You don't want to be elitist about it but you want to be realistic as well."

Policymakers missed their chance to take a good, hard look at the mortgage market and pursue reforms before massive losses mounted. Let's hope they don't repeat the mistake with student lending.

Barb Rehm is American Banker's editor at large. She welcomes feedback to her column at