A consensus is emerging among industry watchers that banks will return to so-called normalized earnings by 2012, with loan losses finally easing to pre-recession levels.

JPMorgan Chase & Co. bolstered that view when it said this week that it saw clear signs of improvement in its troubled mortgage and credit card portfolios in the first quarter.

Mark Fitzgibbon, a principal and director of research at Sandler O'Neill & Partners LP, said JPMorgan Chase Chief Executive Jamie Dimon's positive commentary on the direction of the economy may have done more than reinforce the 2012 timetable.

"If anything, it pushed it up a little bit," Fitzgibbon said.

"They're kind of a bellwether for the industry. People a feel a little bit better. We'll see how next week is," when several other big banks report their first-quarter results.

Chris Kotowski, a banking analyst with Oppenheimer & Co. Inc., agreed, saying a decline in loans at least 30 days past due across JPMorgan Chase's consumer portfolios bodes well for other banks.

"While JPM's earnings remain significantly impacted by the weak economic environment, [its] results increase our conviction that the company's and the industry's recovery is on track," Kotowski wrote in a research note Thursday.

Kotowski is on board with the 2012 deadline. So are analysts with Keefe, Bruyette & Woods Inc., who said in a report last week that they expect more than half of the 175 banks they cover to reach normal earnings that year.

While analysts differ in their math for calculating when and why banks will get back to normal, their underlying rationale is similar for pegging the year as 2012: there is evidence that the amount of money banks have to set aside to cover bad loans has peaked.

Provisions have been falling at large and midsize banks, and chargeoffs appear to be peaking. If that trend holds, these banks could have the bulk of their bad loans cleared from their books within two years.

"We're getting closer to the end," said Todd Hagerman, an analyst with Collins Stewart.

Speculation about normal earnings began in earnest early last year, when the severity of credit losses meant that investors had to start valuing banks by how much they could earn, rather than what they were earning, or losing, as the case may be.

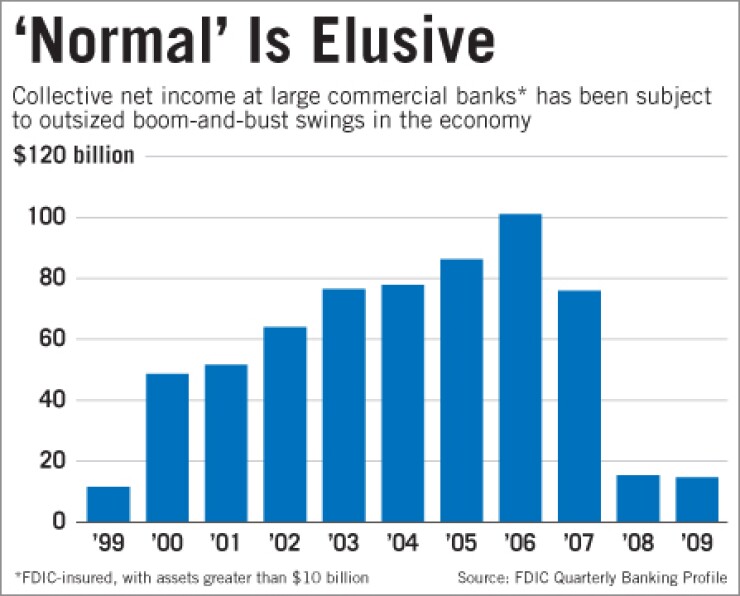

Normal, for the most part, is defined by a lack of unusual charges resulting from swings in the economy. So for banks, credit costs tend to be the key determinant of whether earnings are normal.

Loan losses have been historically high in the past couple of years: Banks had $186.8 billion in chargeoffs in 2009, according to Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. data.

That was up from $99.5 billion in 2008 and up from $26.7 billion in 2006, when things were considered still normal.

A return to normal earnings doesn't mean lenders will start generating the eye-popping profits they enjoyed during the credit boom.

It simply means they will no longer be losing massive amounts of money on bad loans.

"I think expectations need to be appropriate in that a normal environment is just that — it's normal," said Terry J. McEvoy, an analyst with Oppenheimer & Co.

Fitzgibbon said nobody knows what sorts of profits banks will post after the recession fades, though the results will probably be tempered by new regulatory fees and higher capital requirements.

"The earnings levels of the industry will reset at a lower level," he said.

Fitzgibbon said determining normal earnings has been an industry guessing game for a while.

Initial projections from early last year had banks getting back to normal in 2011. The deadline was pushed back in the fall as the unemployment rate kept rising, and it became clear that many had underestimated the severity of the downturn.

Analysts say they are more confident in their latest projection.

"People realized that this is quite a different recession than others," said Maclovio Pina, an analyst with Morningstar Inc. "At this point I would argue, or at least hope, that we have better visibility than we had a year ago."

The 2012 deadline isn't written in stone, of course.

Jason Goldberg, an analyst with Barclays Capital, said banks could be further away from normal than they appear because of steps regulators are taking to help borrowers stay solvent.

For instance, recent proposals to change the federal home loan modification program could keep the housing market from bottoming out by delaying inevitable foreclosures, Goldberg said. That would drag out the time it takes banks to work through problem mortgages.

Other analysts worry that regional banks are not being up front about potential losses in their commercial real estate books, which do not have to be marked to market.

A huge wave of CRE loans underwritten before the recession is to come due in the next three or four years. Banks, at the urging of regulators, have been modifying CRE loans to help borrowers stay on top of their interest payments, even if their loans are underwater. This "extend and pretend" strategy could keep credit costs elevated for longer than anticipated.

David Dietze, chief investment strategist at Point View Financial Services Inc., said modifications are certainly buying time for banks and their borrowers. Whether they are delaying another round of losses depends on how well the economy recovers, he said.

"Even if you are deferring the day of reckoning there is still a chance — and it actually looks more likely today — that a V-shaped recovery takes hold," Dietze said.

"The reality may change in their favor by virtue of a rebound economy."